Cyclopedia (39 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

RELIABILITY TRIALS

Cycling club events in which the participants have to complete a set course within a certain time. There may also be a set minimum time to discourage racing. Unlike CYCLOSPORTIVES, which operate on the same principle, reliability trials do not usually have direction arrows as part of the challenge is finding your own way.

Cycling club events in which the participants have to complete a set course within a certain time. There may also be a set minimum time to discourage racing. Unlike CYCLOSPORTIVES, which operate on the same principle, reliability trials do not usually have direction arrows as part of the challenge is finding your own way.

Â

(SEE

PARISâBRESTâPARIS

,

RAID PYRENEAN

, AND

ÃTAPE DU TOUR

FOR OTHER LONG-DISTANCE CHALLENGES)

PARISâBRESTâPARIS

,

RAID PYRENEAN

, AND

ÃTAPE DU TOUR

FOR OTHER LONG-DISTANCE CHALLENGES)

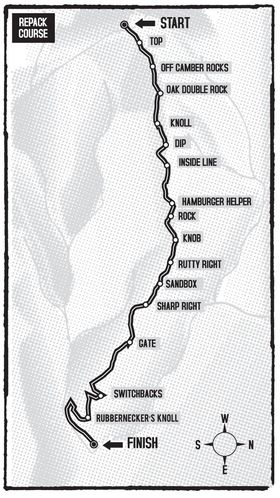

REPACK

Celebrated downhill MOUNTAIN-BIKING course on Pine Mountain, near Fairfax in California's Marin county,just north of San Francisco, where the fat-tired sport was born thanks to a series of informal events using customized bikes run between 1976 and 1979. The events were not organized, but “spontaneously called together when the sun and moon assumed appropriate aspects.” Early racers on the course included GARY FISHER, the “father of mountain-biking”; no more than 200 ever joined him.

Celebrated downhill MOUNTAIN-BIKING course on Pine Mountain, near Fairfax in California's Marin county,just north of San Francisco, where the fat-tired sport was born thanks to a series of informal events using customized bikes run between 1976 and 1979. The events were not organized, but “spontaneously called together when the sun and moon assumed appropriate aspects.” Early racers on the course included GARY FISHER, the “father of mountain-biking”; no more than 200 ever joined him.

Two miles long and dropping 1,300 feet, the course earned its name because the series of tortuous turns meant that the primitive hub brakes of the time would burn out and had to be repacked with grease after each run. “In addition to its incredible steepness it features off-camber blind corners, deep erosion ruts and a liberal sprinkling of fist-sized rocks,” wrote the race organizer Charlie Kelly in an article for

Bicycling

magazine in 1979. Kelly's website contains all the results from his original

notebooks, apart from the first race, which was held on October 21, 1976.

Bicycling

magazine in 1979. Kelly's website contains all the results from his original

notebooks, apart from the first race, which was held on October 21, 1976.

Fisher set the course record of 4 minutes 22 seconds in the seventh race on November 20, 1976. By 1977 prizes were being awarded courtesy of local bike shops, timing was on digital watches, and an endurance event was run that was a precursor of today's cross-country races. The events ended in 1979 after a racer sued a television company when he broke his wrist; the course was resurrected in 1983 and 1984 for officially sanctioned races.

RIVALRIES

Cycling's great conflicts can run deep. In 1992 a journalist visited FRANCESCO MOSER and happened to mention his great rival Giuseppe Saronni; Cecco's tirade against “

il Beppe

” lasted almost half an hour. Ask BERNARD HINAULT about GREG LEMOND and the response is terse, and whatever you do, don't ask LeMond about Hinault, and in particular, don't ask about the way the Frenchman behaved during the 1986 TOUR DE FRANCE. LeMond is still not happy, even though he won.

Cycling's great conflicts can run deep. In 1992 a journalist visited FRANCESCO MOSER and happened to mention his great rival Giuseppe Saronni; Cecco's tirade against “

il Beppe

” lasted almost half an hour. Ask BERNARD HINAULT about GREG LEMOND and the response is terse, and whatever you do, don't ask LeMond about Hinault, and in particular, don't ask about the way the Frenchman behaved during the 1986 TOUR DE FRANCE. LeMond is still not happy, even though he won.

There are two definitive rivalries in cycling, against which all others have to be judged: GINO BARTALI and

FAUSTO COPPI in the 1940s and JACQUES ANQUETIL and RAYMOND POULIDOR in the 1960s. Both relationships remain permanently etched on the national consciousness in Italy and France.

FAUSTO COPPI in the 1940s and JACQUES ANQUETIL and RAYMOND POULIDOR in the 1960s. Both relationships remain permanently etched on the national consciousness in Italy and France.

Bartali and Coppi started out as teammates in the 1940 GIRO D'ITALIA, where the younger Coppi upstaged his older boss to win the event. Their rivalry was at its most intense after the war and reached its nadir at the 1948 world championship in Holland, where the pair watched each other like hawks, eventually getting fed up with it and heading to the changing rooms. It took elaborate negotiation by the Italian national team manager ALFREDO BINDA merely to get them to start the Tour de France in 1949 in the national team; on the road there were constant accusations of double-dealing from both men and their backers. Time and again, Binda had to bang their heads together; by the 1952 Tour, Bartali had finally accepted Coppi's superiority.

Most of the time the pair had a good relationship off their bikes, but the rivalry was massively important to the press. Every time either said anything about the other man, it was headline news; as for their fans, they would argue bitterly in bars and still do so today. On the road it only needed one to have the slightest problemâa puncture, an unshipped chainâfor the other to attack. They devised elaborate strategies against each other: Bartali detailed a teammate to watch Coppi's legs and warn him the moment the vein behind his knee began pulsating, as that was a sign he was weakening. Coppi asked his teammates to take Bartali out on the town before the 1948 MILANâSAN REMO, in the hope that they would have a long night out and the “old man” would be tired the next day. They sent spies to spread disinformation, Bartali would get a teammate to search his rival's hotel room for drugs.

ANQUETIL and POULIDOR had a different relationship: there was no bitterness, at

least on Poulidor's side, and the rivalry clearly served as an extra form of motivation for “Master Jacques.” In 1967, the night before the Critérium National one-day race, he was quaffing whisky at 3 AM with his manager Raphael Geminiani when “Gem” suggested they drink to Poulidor's win the next dayâAnquetil was not planning to rideâbut the joke backfired. Anquetil told his wife Janine to set his alarm clock for 7 AM, and duly won the race.

least on Poulidor's side, and the rivalry clearly served as an extra form of motivation for “Master Jacques.” In 1967, the night before the Critérium National one-day race, he was quaffing whisky at 3 AM with his manager Raphael Geminiani when “Gem” suggested they drink to Poulidor's win the next dayâAnquetil was not planning to rideâbut the joke backfired. Anquetil told his wife Janine to set his alarm clock for 7 AM, and duly won the race.

Poulidor and Anquetil's rivalry did not last as long as the 15-year conflict between Bartali and Coppi, but made as big an impression: 30 years later, French politicians were still being asked who they supported. Anquetil could never quite understand why, for all his success, the French public always preferred the underdog, Poulidor. “Of course I would like to see Poulidor win the Tour in my absence. I have beaten him so often that his victory would merely add to my reputation.”

While Moser's rivalry with Saronni was essentially a parody of the Coppi/Bartali conflict, largely the product of the Italian press, REG HARRIS and the Dutch sprinter Arie van Vliet were bitter enemies for a short while. They were initially friends, but fell out after Harris told his fellow Englishman Cyril Bardsley to appeal to the judges after Van Vliet put a pedal in his wheel in the 1958 world championship. To fan the flames, Harris accused Van Vliet of being soft, saying “he's never been out in a cape and sou'wester and ridden in the rain for eight hours.” After that, Van Vliet would recruit other riders to help him against Harris and the pair had occasional shoving matches in races. “An enormous bloody war,” Harris termed it. “Every time Arie said âLook isn't it time this was over?' I'd say âIt'll never be over as far as I'm concerned.'”

Some of the bitterest episodes have involved cyclists on the same team. The Coppi/Bartali dispute had its origins when the pair raced together at the start

of Coppi's career. Hinault and LeMond fell out because they both wanted to win the 1986 Tour, in which the Frenchman had promised to help LeMond but appeared to go back on the deal. The 1987 GIRO D'ITALIA saw an epic conflict between STEPHEN ROCHE and his nominal leader Roberto Visentini.

of Coppi's career. Hinault and LeMond fell out because they both wanted to win the 1986 Tour, in which the Frenchman had promised to help LeMond but appeared to go back on the deal. The 1987 GIRO D'ITALIA saw an epic conflict between STEPHEN ROCHE and his nominal leader Roberto Visentini.

There were echoes of the Roche/Visentini battle in the 2009 Tour, when LANCE ARMSTRONG contested team leadership with the Spaniard Alberto Contador, who was isolated within the Astana team. Armstrong briefed against the Spaniard, attacked him early in the race, and in the final week Contador was to be seen hitching lifts with rival teams and his brother to get to his hotel after stage finishes.

In track racing GREAT BRITAIN and AUSTRALIA were bitter rivals in the early 21st century. In racing component manufacture, SHIMANO and CAMPAGNOLO compete intensely and had a stranglehold on the sport that has only recently been threatened. But the last word on rivalries should go to Anquetil, who had a thought for Poulidor even on his deathbed, where he said a final goodbye to him with the words: “Sorry, Raymond, you're going to finish second again.”

ROAD RACING

Began on November 7, 1869, with the running of ParisâRouen, organized by the magazine

Le Vélocipede Illustré

, which published the rules on October 20. The course was 135 km beginning at the Arc de Triomphe with five checkpoints en route. The race was open to “all velocipedes, all mechanical devices powered by the force of a man, by weight, foot and hand action, monocycles, bicycles, tricycles, quadricycles or polycycles. They may only convey

one person, who will drive and direct the machine, which he may not change during the race.” Walking by the machine was permitted, as were repairs en route. The riders were banned, however, from taking dogs with them or entering under false names. They were permitted to eat and drink, to wear what they wanted, but they were banned from giving each other any assistance such as “pulling each other by cords or chains.” Entry was free, and a time limit of 24 hours was set. First prize was 1,000 francs, second prize a “double suspension” velocipede.

Began on November 7, 1869, with the running of ParisâRouen, organized by the magazine

Le Vélocipede Illustré

, which published the rules on October 20. The course was 135 km beginning at the Arc de Triomphe with five checkpoints en route. The race was open to “all velocipedes, all mechanical devices powered by the force of a man, by weight, foot and hand action, monocycles, bicycles, tricycles, quadricycles or polycycles. They may only convey

one person, who will drive and direct the machine, which he may not change during the race.” Walking by the machine was permitted, as were repairs en route. The riders were banned, however, from taking dogs with them or entering under false names. They were permitted to eat and drink, to wear what they wanted, but they were banned from giving each other any assistance such as “pulling each other by cords or chains.” Entry was free, and a time limit of 24 hours was set. First prize was 1,000 francs, second prize a “double suspension” velocipede.

Other books

Brittle Shadows by Vicki Tyley

The Seventh Sacrament by David Hewson

Taking Him (Lies We Tell) by Ashenden, Jackie

The Versace League by Shan

Morning Glory by LaVyrle Spencer

Bulls Rush In by Elliott James

Moskva by Jack Grimwood

Behind His Eyes - Consequences by Aleatha Romig

Power Systems by Noam Chomsky

Revenge of the Tide by Elizabeth Haynes