Read Daily Life In Colonial Latin America Online

Authors: Ann Jefferson

Daily Life In Colonial Latin America (35 page)

In the realm of sexuality and love, people’s real lives

seem to have diverged considerably from the model prescribed by the church, and

in a way, the post-independence instability served to lessen the threat to

people’s private lives posed by the authorities. Not only is there substantial

evidence of homosexual activity, but baptismal records show high levels of

children born to unmarried parents and appreciable numbers of children who were

the product of adulterous relationships. Significant numbers of children were

also fathered by priests. The surviving evidence shows that punishments were

inflicted on enslaved workers who had sneaked off the plantation to visit a

loved one, an outcome they surely could have anticipated but seem to have been

willing to risk. The church faced a challenging task as it attempted to apply

its moral precepts to the people of the Americas, especially since many people

had roots in African or indigenous societies that held views on sexuality that

diverged widely from Catholic teachings.

In elite circles, however, the church had better success.

As the recognized authority on appropriate behavior both inside and outside the

house, the church used its power to set the parameters of acceptable sex. Since

elite families had a lot to lose, specifically the family honor and good name,

intangibles that carried little significance among the common people, they went

to great lengths to create at least the appearance of propriety. In chapter 1

we saw that several couples who seem to have felt a deep commitment to each

other were separated, for years or forever, by parents and priests who valued

the family’s status above the wishes of the young couple. A premarital

pregnancy might pose a serious threat to the family honor too, in which case

all the family members conspired to hide the evidence of this divergence from

the church’s moral code.

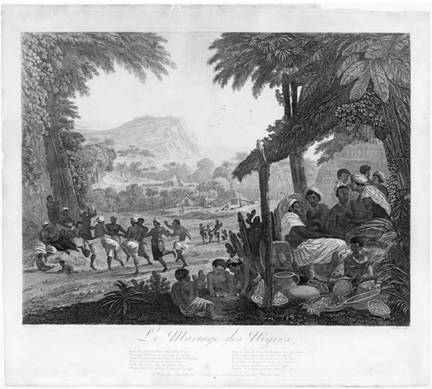

A 1795 image from

revolutionary-era Paris, home to the abolitionist Society of Friends of Blacks.

The image is accompanied by a poem celebrating the capacity of slaves, “friends

of reason,” to recognize and enjoy what the poet describes as the social

virtues of marriage.

The culture of sexuality that characterized elite society,

obsessed as it was with concerns of family honor and adherence to church

guidelines, diverged widely from that of the masses of working people. This

suggests that these two widely divergent sexual cultures would leave two

distinct legacies to people of the postcolonial period, and this is indeed what

happened. Elites struggled to keep up the appearance of propriety after

independence, as they had before, while the common people enjoyed greater

success in avoiding the authorities, now quite busy with matters of state. Many

of the popular classes managed to do as they liked, discretely in most cases,

and stay out of sight and out of reach of the law.

As in matters of sexuality, the responses of ordinary

people to the efforts of the authorities to control their lives often took the

form of quietly pursuing their interests as best they could either within or

outside the law, while avoiding direct confrontation with the powerful forces

that backed the social order. But confrontation, violent or not, was sometimes

unavoidable, since in practice popular resistance was often the only curb on

the ambitions of the wealthy and powerful, in whose favor the law tended to

operate. The colonial era is full of examples of such resistance, whether in

the form of moral challenges to the lawless behavior of elites through a court

system that was supposed to protect the weak or in the form of armed unrest.

Yet even the wars of independence, in a certain way the greatest example of

violent resistance to authority, produced few fundamental changes in societies

marked by profound inequalities in the distribution of wealth and power. Simply

put, the struggle for daily survival among the poor and mostly nonwhite

majority created almost insurmountable difficulties to organizing on the scale

necessary to overcome tight-knit elite groups whose ancestors had violently

seized control over the vast majority of Latin America’s resources.

And yet, there were victories. The Haitian Revolution

stands as a remarkable testament to the determination of people to free

themselves from oppressive conditions of work and life. The attempt at social

revolution by Hidalgo and Morelos in Mexico, although a military failure,

nevertheless contributed to the emergence of a republic that with all its post-independence

problems elected a full-blooded Indian, the Zapotec Benito Juárez, as president

less than 50 years after the end of a colonial regime founded on the subjugation

of the native population. Even in Brazil, where African slavery lasted longer

than anywhere else in the Western Hemisphere, outbreaks of slave resistance of

the sort that had troubled planters since the early colonial era helped bring

down the institution at last in 1888. There is no reason to suppose that any of

these developments would have occurred had the social hierarchy that the

Spanish and Portuguese worked so hard to impose on their colonies in the

Americas been accepted without complaint by those who were relegated to its

bottom reaches.

A FINAL WORD

Any deep understanding of Latin America rests firmly on a

base of colonial life as it was lived by the people of the region over the 300

years from the arrival of Columbus in the Caribbean in 1492 to the surrender of

the last Spanish loyalists on the mainland at the port of Callao, Peru, in

1826. The people already living in this hemisphere, the invaders from the

Iberian Peninsula, and the people brought from Africa to work came together to

talk, to fight, to worship, to eat and drink, to work and play, and to have

sex, some willingly and some against their will. They were born, lived their

lives, had children, and died, building societies, economies, and political

structures that slowly evolved over the period. And they bequeathed to those

who came after a legacy that set the terms of the early post-independence

period.

Some of the patterns and institutions they established have

disappeared, like the old coerced labor systems, but others are still important

today. The large estate, the patriarchal extended family, and the social

structure based on racial characteristics have lived on over the 200 years

since independence and are still very much alive in parts of the region,

structuring daily life as it is lived by Latin Americans in the 21st century.

In this study, we have tried to get as close as possible to the daily lives of

the people of the 17th and 18th centuries and to examine how they lived within

or across social boundaries, how the legal apparatus structured their lives or

failed to, and how at times they accepted and at other times rejected the world

they were born into, or brought into. Latin America today is the result of what

they did every day.

GLOSSARY

adobe

—Housing material of bricks made from mud, usually with a heavy

clay component,

mixed with straw and dried in the sun.

alcalde

—Municipal administrator in Spanish America.

aldeia

—Jesuit-run settlement in early colonial Brazil where native

peoples were congregated for purposes of Christianization and, in theory,

protection from enslavement.

altiplano

—Highlands.

arriero

—Mule driver.

atol

—Porridge or hot drink, usually based on a starch (e.g., maize,

plantain).

audiencia

—Large Spanish American administrative region governed by a high

court of the same name; there were several

audiencias

in each

viceroyalty.

bandeirante

—Participant in slaving expeditions sent up vast inland waterways

into the Brazilian interior from settlements like São Paulo.

barracoon

—Large, dormitory-like sleeping quarters on an estate used to

house the enslaved population.

cabildo

—Spanish American municipal council.

caboclo

—Term applied to people of mixed, often Portuguese-native,

ancestry in northeastern Brazil.

cachaça

—Alcoholic beverage in Brazil that was produced from sugarcane

juice.

calidad

—Social rank or status.

Carrera de Indias

—Spanish fleet system.

casa grande

—Main house.

casta

—General term applied to all persons of mixed ancestry in Spanish

America.

charqui

—Meat jerky.

chicha

—Andean corn beer; major source of alcohol consumption in the

Andes prior to Spanish arrival.

chile

—Pepper.

chuño

—Freeze-dried potatoes.

cimarrón

—Escaped slave, frequently living in an outlaw community with

other escapees.

cofradía

—A confraternity, or lay religious brotherhood, in Spanish

America.

colegio

—Private school generally run by a religious order.

comal

—Stone griddle for heating corn tortillas in Mexico and Central

America.

consanguinidad

—State of being related to someone by blood.

corregidor

—Regional administrator in Spanish America; duties included the

regulation and defense of the native population.

correo mayor

—Postmaster general.

criollo/a (Port. crioulo, Eng. creole)

—Term originally applied to an

enslaved person of African descent born in the Americas or the Iberian

Peninsula; later came to mean Spaniard born in the Americas as well.

curandero/-a

—Popular healer, often a woman of indigenous or African origin.

debt peon

—Individual tied to a rural estate or other economic enterprise by

debts originating in advances offered by an owner seeking a resident labor

force.

dispensa

—Church waiver of an impediment to marriage.

encomienda

—Grant to an individual Spaniard of labor and tribute from one or

more native villages; most

encomiendas

eventually reverted to the

Spanish crown.

engenho

—Brazilian sugar mill; often applied in the sense of

plantation

to an entire sugar-producing operation, including canefields.

expediente matrimonial

—Marriage document prepared by the priest

who interviewed a prospective couple.

farinha

—Manioc flour.

forastero

—Term applied to outsiders in native villages, often indigenous

people who had fled labor and tribute obligations in their own communities.

fr

ij

oles

—Beans.

garapa

—A type of sugarcane alcohol in Brazil.

gaucho (Port. gaúcho)

—Ranch hand, cowboy in the Southern Cone of South America.

hidalgo

—Member of the minor nobility

in Spanish realms.

huipil

—Women’s top, blouse.

Inquisition

—Roman Catholic tribunal charged with rooting out and punishing

heretical beliefs, witchcraft, and other thoughts or behavior considered to

deviate from religious orthodoxy; jurisdiction in Latin America restricted to

the nonnative population.

irmandad

—A lay religious brotherhood in Brazil.

kuraka

—Local ruler/chieftain among indigenous Andean peoples; often a

descendant of pre-colonial Andean nobility.

laborío

—Alternative tribute levied in Spanish America on free people of

African ancestry and natives not bound to specific villages by labor and

tribute obligations.