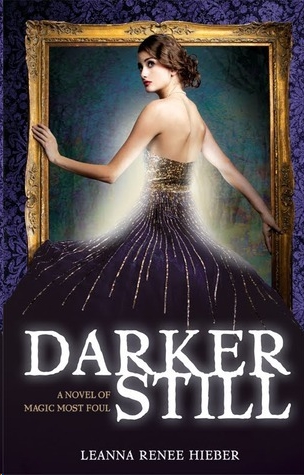

Darker Still

Authors: Leanna Renee Hieber

Tags: #Young Adult Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #United States, #19th Century, #Romance, #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Love & Romance

Copyright

Copyright © 2011 by Leanna Renee Hieber

Cover and internal design © 2011 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Andrea C. Uva

Cover photography by Patrick Fleischman

Cover images © Don Bishop/Getty Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Fire, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Contents

To all who have struggled to make their voices heard, historically and presently

New York County, Municipal Jurisdiction

Manhattan, July 31, 1880

New York City Police Record Case File: 1306

To whoever should have the misfortune to review this closed—but still unresolved—case, I extend my condolences. I tell you truly that all persons involved have been insufferably

odd

.

All we know directly of Miss Natalie Stewart, disappeared at age seventeen, is what you will read here in what was left behind as an absurd testimonial.

Herein you shall find pertinent newspaper articles enclosed by Miss Stewart regarding Lord Denbury and his infamous portrait. There are also letters from involved parties.

I am left to conclude that everyone involved is a certifiable lunatic. Should you wish to indulge yourself and read a young lady’s foolish reveries on such highly improbable events, so be it. Should you

believe

any of it, I hope you have no business with the New York Police Department now or in the future.

Regards,

Sergeant James Patt

This Journal is the sole property of:

Miss Natalie Stewart

As a gift to mark this, her exit from

The Connecticut Asylum

June 1, 1880

Sister Theresa handed me this farewell gift with such relief that it might as well have been a key to her shackles. I’m a burden to her no more. Someone else will have to glue her desk drawers closed and exchange her communion wine for whiskey.

But now I trade the prison of the asylum for another. The prison of home.

Oh, I suppose I ought to clarify the word

asylum

, as it has its connotations.

The only illnesses the students of the Connecticut Asylum have are those of the ears and the tongue. The mute, or the deaf, are not the mentally ill. Those poor souls are cloistered someplace else, thank God. We had enough troubles on our own.

But now that I’m home, a prison undercurrent is here too. The desperate question of what is to be

done

with me lingers like dark damask curtains, dimming the happy light of our dear little East Side town house. For unfortunates like me, firstly, a girl and, secondly, a mute girl, life is made up of different types of prisons, I’ve learned. If I were a man, the world could be at my command. At least it would be if I were a man and could speak.

Every night I pray the same prayer: that I may go back to that year of Mother’s death and startle my young self to shake the sound right out of that scared little girl. Maybe I’d have screamed. A beautiful, loud, and unending scream that could carry me to this day. A shout that could send a call to someone, anyone, who could help me find my purpose in this world. But since that trauma, I’ve yet to utter a word. Not for lack of trying, though. I simply cannot seem to get my voice through my throat.

I’ve often thought of joining a traveling freak show. At least there I wouldn’t have to deal with the ugliness of people who at first think I’m normal and then realize I can’t speak. I

hate

that moment and the terrible expression that comes over the person’s face like a grotesque mask. The apologetic look that thinly veils pity but cannot disguise distaste, or worse, fear. If I were already in a freak show, people would be forewarned, and I could avoid that moment I’ve grown to despise more than anything in the world. But would I belong beside snake charmers and strong men, albinos and conjoined twins? And if not, where do I belong, if anywhere?

• • •

As a child, I heard a Whisper, a sound at the corner of my ear, and saw a rustle of white at the corner of my eye. I used to think it was Mother. I used to hope she would show me how to speak again or explain that the shadows I see in this world are just tricks of the eyes. But she never revealed herself or any answers. And I stopped believing in her. I stopped hearing the Whisper. But what

does

remain are the shadows that come to me at night. There are terrible things in this world.

I don’t have pleasant dreams. Only nightmares. Blood, terror, impending apocalypse. Great fun, I assure you. (Perhaps it’s good I can’t speak; I’d share dreams at some normal girl’s debutante ball and send her away screaming or fainting.) There are times when I feel I need to scream. But I can’t.

I’ve so much to say but don’t dare open my mouth. The sounds aren’t there. I tried, years ago. Therapists soon gave up on me, saying I was too stubborn. But it wasn’t me being

stubborn

. I was anxious, nerve-racked, afraid; I hated the foreign, unwieldy sound that crept out from behind my lips so much so that I haven’t dared try since. Perhaps someday.

That’s why I was given this diary. Other girls were given lockets or trinkets. When I’ve nothing to occupy my mind or my hands, I resort to mischief. Now if the asylum had just had more books (I’d read them all,

twice

, within my first two years), I’d never have bothered with the communion wine. I wouldn’t have had the time for glue, tacks, or spiders.

I’d have been reading about trade routes to India, the impossible worlds of Gothic novels, or even the tedious wonders of jungle botany—

anything

other than this boring, dreary world we live in. And so, dear diary, you’ll bear my written screams as I yearn for a more industrious, exciting life.

Unless I find an occupation or a husband, which in my condition is laughable, I’m destined to languish in solitary silence. Most men of Father’s station would have whisked me off to some country ward upstate never to be seen again. (I’ve been continually reminded of this by scolding teachers who insist I ought to be more grateful for a doting father.)

And I

am

grateful for sentimentality on Father’s part. I look too much like Mother for him to have sent me off, and goodness, if my sprightly nature doesn’t remind him of her. So I’ve always felt a certain security in my place here a few blocks from Father’s employer, the ten-year-old Metropolitan Museum of Art. A building and an institution I’ve come to adore.

Tonight, Father’s having a dinner party with his art scholar friends. They’re quite boring, save for his young protégé, Edgar. I could suffer Edgar Fourte’s presence under

any

circumstance. But make no mistake, I positively hate that wench he proposed to. If only I could have fashioned some mad plot and sent Father away, I would have thrown myself at Edgar’s mercy and become his lovely, tragic young ward. I’d have made myself so indispensable to him, not to mention irresistible, he’d never have considered another woman.

I’ve been told I’m pretty. And he’s a man who likes quiet. What could be more perfect than a pretty wife who doesn’t speak? But alas, I’ll have to find some other handsome young scholar with a penchant for unfortunates since Edgar stupidly went and got himself engaged to one. So what if she’s blind? She can’t see how beautiful he is. What a waste!

Ah, the clock strikes. I must help Father with preparations and then make myself

particularly

presentable, if nothing else than for Edgar’s punishment. I’ll return with any notable gossip or interesting thoughts.

Later…

They’ve clustered into Father’s study for a cigar, having stuffed themselves as scholars do at a meal they didn’t pay for themselves, leaving me a few moments with these dear pages.

We’re in luck; they

did

discuss something fascinating at dinner.

An odd painting is coming to town. An exquisite life-sized oil of a young English lord named Denbury is about to arrive for a bid. And they say it’s haunted.