Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (19 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

Yuri “Georgy” Krivonishchenko takes a photo, January 27, 1959

To keep their energy up, the skiers had purchased four loaves of warm bread at Sector 41, and, over the course of the night, they split two of the loaves among themselves. Meanwhile, Grandpa Slava’s horse seemed to move ever more slowly over the perilous river, and despite the skiers’ own cautious pace, the Lithuanian and his sleigh eventually disappeared from view behind them.

At last, in the light of the three-quarter moon, the travelers were able to make out a cluster of snow-capped rooftops. As they approached, the settlement seemed to grow into a full village, but there would be no villagers to receive them tonight. There were around twenty cabins, all silent, with no fire or candlelight in a single window. The skiers moved down the trackless streets, past doors and windows that had been left or blown open—and in the moonlight, they could make out the outlines of forsaken stoves and furniture inside. The settlement had been abandoned two or three years before, but, to look at it, one might have imagined

the inhabitants of these cabins just having been forced to leave at a moment’s notice, having no time to collect their furniture or to latch their doors before leaving their homes forever.

The woodcutters had informed them that only one of the houses was in suitable condition for spending the night, and it took some effort to find it. In his diary, Doroshenko noted the discovery of the house—discernible from the water hole cut in the ice—and the late arrival of Velikyavichus.

We found it late at night and guessed the location of the hut only by a hole in ice. Made fire out of boards. Stove is smoking. Some of us hurt our hands on the nails. Everything’s OK. And the horse arrived. And then, after dinner, in a well-heated hut, we were bantering till 3:00

AM

.

The girls took the available beds, and the men—Grandpa Slava included—spread out on the floor with their sleeping bags. Despite the growing pain in his leg, Yudin chose to believe that he’d feel better in the morning.

When Yudin awoke and tried to pull himself off the floor into a standing position, it became apparent to everyone, including Yudin, that it would be foolish for him to continue on the trip. Besides, this was his last opportunity to head safely back to civilization. From here on, there would be no more settlements—only forest—and the group couldn’t risk having to carry Yudin out should he be unable to move. And so it was decided that he would return home. Kolya wrote in the group’s diary:

Sure is a pity to part with him, especially to me and Zina, but it can’t be helped

.

While Grandpa Slava was readying his load of iron pipes to take back to Sector 41, Yudin gathered as many minerals as he could find scattered around the area, mostly pyrite and quartz, and piled them into the sleigh. “The man with the horse was in a hurry,” Yudin remembers, “and yelled for me to hurry up.” Yudin regretted having to leave his friends, but he adopted his usual smile and reminded himself that they’d be reunited in ten days. After a round of warm hugs, he left the nine to continue the trek to Otorten Mountain without him. He loaded his pack onto the sleigh, but the extremely cold pipes prevented him from hitching a ride himself. And so with aches shooting through his legs and back, Yudin skied after Grandpa Slava and the horse all the way down the 15 miles of winding river.

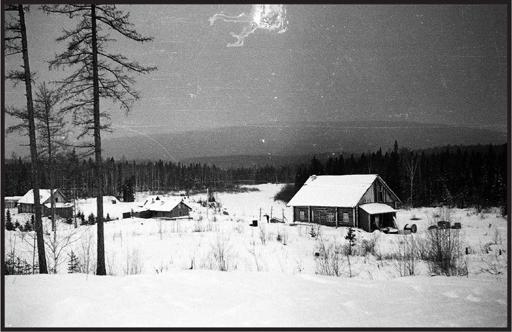

The abandoned cabin where the Dyatlov hikers stayed, January 28, 1959.

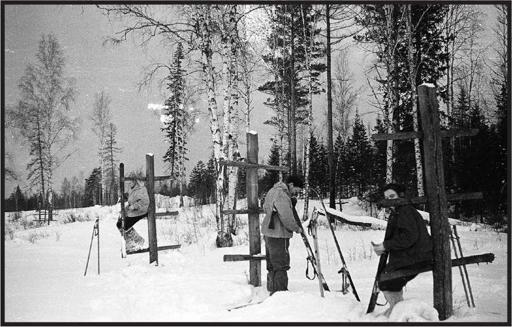

The Dyatlov hikers rest on the geologists’ shelves in the abandoned village. From left to right: Lyudmila “Lyuda” Dubinina, Alexander “Sasha” Zolotaryov, Zinaida “Zina” Kolmogorova, January 28, 1959.

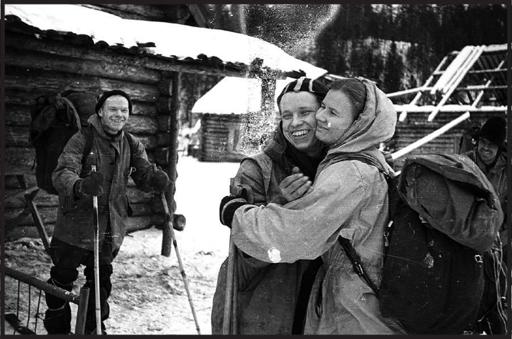

Yuri Yudin shares a final hug with Lyudmila “Lyuda” Dubinina before returning home. Igor Dyatlov looks on, January 28, 1959.

16

FEBRUARY–MARCH 1959

AFTER NEWS OF THE FOUR BODIES REACHES SVERDLOVSK

, and the initial shock sets in, friends and family of the hikers begin to cast about for someone to blame. Many hold the university responsible for allowing students to embark on such dangerous expeditions in the first place. There are additional rumblings around this time that investigators should be directing their inquiries toward the native people of the region. When Mansi tracks are discovered not far from the hikers’ route, the question arises: Did the tribe resent Russians intruding on their sacred territory? To address the growing suspicions, foresters who work in proximity to the Mansi are brought into Ivdel for questioning.

Forester Ivan Rempel, who had met the hikers in Vizhay a week before their disappearance, is unequivocal in his defense of the Mansi. “I believe it’s impossible,” he remarks in his testimony of early March, “because I meet Mansi often and don’t hear any hostile words toward other nations from them. They are very hospitable when you visit or meet them.” Rempel also points out that the area where the hikers traveled is not sacred tribal land. “Local residents say that sacred rocks of the Mansi are at the Vizhay riverhead, 100 to 150 kilometers from the place of the hikers’ deaths.”

As for signs that the Mansi had been shadowing the hikers, Vizhay forester Ivan Pashin rejects the evidence in his testimony to

investigators: “At one kilometer from the first stopping place of the hikers, we saw a Mansi standing site where they pastured reindeer, but it was after the hikers’ deaths, because the Mansi tracks were fresh, and the hikers’ [camp] looked old.” He concludes, “Mansi could not have attacked hikers. On the contrary, knowing their habits, they help Russians. . . . Mansi have taken lost people into their homes and sustained them by providing food.”

Andrey Anyamov, a Mansi hunter and reindeer herdsman from Suyevatpaul, had been hunting near the Auspiya River in late January, around the time the hikers had been in the area. When he and his companions are brought to Ivdel for questioning, he tells investigators, “All four of us saw ski tracks, but we didn’t follow them. We saw trails of moose, wolves, wolverines, but didn’t see fire places or hear human voices.” As for the idea that the area held any religious significance for the tribe, Anyamov’s hunting partner, Konstantin Sheshkin, points out: “There’s no sacred mountain in our hunting places. . . . But now the Mansi don’t visit sacred mountains. The youth don’t pray at all, and elders pray at home.”

After several interviews of this nature, it becomes clear to investigators that, aside from there being zero physical evidence of Mansi involvement, a people known for their harmonious nature could hardly have orchestrated an event that would have sent the hikers to their deaths.

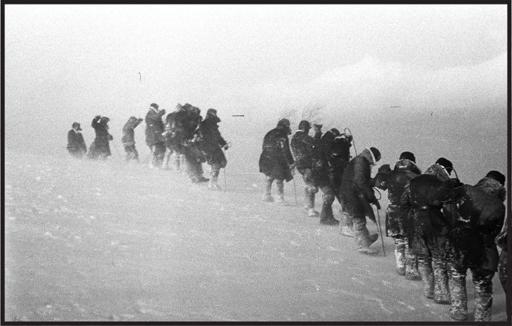

Back on Holatchahl mountain, the search party—which still includes Mansi volunteers—is discarding all hope of finding any of the Dyatlov group alive. This is now a recovery mission, and the searchers are left with the grim task of locating five snowy graves. Maslennikov orders an area of 30,000 square yards to be probed by a team of thirty men. Some of the searchers have been using ski poles to plumb the depths of the snow, but when the probes Maslennikov ordered from his factory arrive, they are able to reach a new depth of over eight feet. The men, clad in near-identical coats and trapper

caps arrange themselves in shoulder-to-shoulder chains in front of a patch of ground. Then, steel in hand, they advance over the landscape, stabbing at the snow, like a small army whose enemy is beneath their feet. It is an exhausting and imperfect system, and the men encounter patches where the probes fail to reach the ground. There is one particular ravine that is roughly 15 feet deep. Via radiogram, an official in Ivdel suggests sending miners with metal detectors to the mountains.

Search teams probe the area for the hikers, February—March, 1959.

Maslennikov replies:

MINERS NEED PROBES RATHER THAN METAL DETECTORS AS PEOPLE UNDER SNOW DON’T HAVE METAL THINGS.

But Maslennikov’s opinion on the matter is ignored, and the next day a team of miners arrives, metal detectors in tow. After a day or two of sweeping the ground and finding nothing, the miners

realize that Maslennikov was right. Whatever watches or metal accessories the hikers might have been wearing is not enough to set off the detectors. So the miners trade in their machines for probes and join the files of men stabbing at the snow.

On March 1, Lev Ivanov arrives on the scene. Ivanov is not replacing Tempalov as lead investigator because of any particular incompetence on the latter’s part; the discovery of the bodies merely requires a higher level of oversight, and Ivanov’s regional scope trumps Tempalov’s municipal one. In addition to his title as junior counselor of justice, Ivanov is a World War II veteran, a husband and a father. He is too obsessed with work, however, to be described by his wife and two young daughters as a family man—and that spring, the Dyatlov case will only take him farther away from his family for longer periods of time. In the coming months, as Ivanov makes multiple trips into the northern Urals, the topography around Holatchahl mountain will become forever etched in his mind.

Ivanov’s first order of business is to board a helicopter and familiarize himself with the locations where the bodies were discovered. There is little to be seen in the places where Zina and Dyatlov had fallen, but the site of the 25-foot cedar tree yields more clues. Examining the charred cedar branches at the fire pit, Ivanov determines that the fire had not burned for more than two hours. It is also apparent from broken branches found nearby, that one of the men had climbed the tree and had likely fallen in the process of cutting away branches. Cedar trees are dry and fragile, and the bough may have given way beneath him. This would be consistent with the cuts and bruises found on Doroshenko’s body, as well as the branches found beneath him. Once the men had started the fire, it would have been large enough to warm them, but not large enough to keep it burning for long. There are also additional footprints, leading Ivanov to believe that at least one other person besides Doroshenko and Krivonishchenko had been present at the site of the tree. There is also evidence of firewood

and fir twigs having been gathered for the fire, but not used. The obvious question, then, besides why the hikers had been only half-dressed with no shoes, is: Why gather perfectly good firewood, but let the fire go out? Ivanov records what information he can from the location, and as he heads back up the slope to commence his formal inspection of the tent, he considers the puzzle.