Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (21 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

As I stood there, below the image of a U-2 spy plane falling to earth, I calculated that Powers would have been grounded exactly fifteen months after the Dyatlov hikers perished. My brain, I realized, needed to connect everything back to the hikers, no matter how tangential.

The station was becoming busy, though I didn’t notice anyone besides us hauling around backpacks and ski equipment. The life of a

tourist

evidently wasn’t what it had been during Khrushchev’s Thaw, and no one here seemed to think it a good idea to go marching in the general direction of Siberia in the middle of winter. As our departure time drew near, I purchased a handful of Russian chocolate bars from a station vendor, stowing them in my pack as a reward for when we reached the location of the tent. When I rejoined my companions, I took out my point-and-shoot, intent on getting a departing shot of the station. But as I was about to snap a shot of the lobby, Kuntsevich and Borzenkov reached out their hands to block the lens. Photos were not welcome in the station, though without a translator, they had difficultly telling me why.

Before we boarded the train, we met the fourth member of our group, Dmitri Voroshchuk, a recruit of Kuntsevich’s. Beneath his manicured beard and wire-rimmed glasses, I could see that he was in his late-thirties, tops, no older than me. In his modest English, Voroshchuk explained that he was a professional geologist who had a strong interest in the case and a love of the Ural Mountains.

I was pleased with our four-man group, as we each had a specific purpose. As an outdoor disaster expert with an emphasis on avalanche studies, and having served as vice president of the Union Federation of Tourism, Borzenkov would be our navigator.

Voroshchuk, although not a professional interpreter, knew enough English to allow us to communicate more clearly. And because he was also a geologist, he would be able to give us insights into the topography of the area. Kuntsevich, with his twenty-five years of intimate knowledge of the case, and scout leadership skills, was clearly the team leader. And finally, being the observer of the group, I was the natural pick for team diarist. I was also the first American, so I was told, to attempt this particular trek to the northern Ural Mountains in the winter.

There were beds on both sides of the train car: bunk beds on one side, single Murphy beds on the other. We stowed our packs in the overhead racks and made our way to the apple-red benches lining the cars. Before I could take my seat, Kuntsevich cordially placed the standard white sheets and blue pillowcases, handed to us upon boarding, beneath us. We pulled out the foldout tables and poured ourselves tea from a thermos. We settled in and tried to pretend that we weren’t all completely on top of one another, and when we brought our plastic cups to our lips, we took special care not to knock our elbows into our neighbor’s tea.

Although we were traveling in a third-class common carriage, or

platzkart

, our comfort level was much higher than that of the Dyatlov hikers. As Borzenkov explained to me, their carriages would have been wooden and without upholstery. Heating was available to them, but not like the steam bath we were currently experiencing in our bulky winter outfits. In addition to their having traveled on a much slower train, the Dyatlov group had to switch trains in Serov; whereas we’d be traveling directly to Ivdel with a stopover in Serov.

As the train left Yekaterinburg, the sun was just beginning to rise, casting its glow over the cheek-by-jowl city of old and new, of pastel masonry and glass. Borzenkov wasted no time in pulling out his artist’s pad to illustrate the route we’d be taking, and how

it compared with the Dyatlov route. I’d brought a small notebook and a pencil broken in half to save space. I had jettisoned my pen after Borzenkov informed me that ballpoints were unreliable in subzero temperatures; the ink would freeze.

For lunch, Kuntsevich produced a container of what resembled a purple Jell-O dessert, but instead of fruit, it was stuffed with herring, potatoes, boiled beets and mayonnaise—all topped with slices of onion. The name of the dish, “herring under a fur coat,” was a pretty accurate way of describing how it felt on one’s tongue, and when I was offered some, I took the politest of bites. To my relief, I had a meal of my own. Olga had slipped me a bag before we left, which contained my favorite chicken dish. I downed it hungrily between gulps of tea.

After our meal, a satiated silence settled over our group. I stared out of my window and watched old power lines fly by, their poles sticking out of the snow at odd angles, like giant crosses. I rarely travel by train in my own country, but when I have, I’ve noticed the hypnotic effect it produces. The thundering below put me in a meditative state as I reflected on the past couple of weeks in Yekaterinburg. They’d been mostly encouraging, and I had been extraordinarily lucky to get to know the famously reclusive Yuri Yudin.

But my trip had not been entirely positive. Earlier in the week, a reporter from a Yekaterinburg TV station had shown up at Kuntsevich’s apartment to interview me. Through a translator, he had repeatedly asked me how much money I was making from my book—the implication evidently being that I had come all this way to exploit a foreign mystery for profit. Money was not a factor in my visit to his country, I told him, resisting the temptation to laugh at the idea that one gets rich in publishing. I also resisted telling him that I’d had no notion of a book deal when I’d begun the project. And I didn’t tell him how conflicted

I felt about having self-financed this entire three-year endeavor, maxing out credit cards and draining my savings account—all the while starting a family.

The reporter had continued with his questions: “What if you don’t feel anything if and when you make it to the location where the hikers died?” and “Why would you, an American, care about Russian hikers who died long before you were born?” I had answered these questions as best I could, without getting too defensive. Still, the reporter’s interrogation lingered long after the interview ended, as if he had gotten at something I was afraid of examining.

Over the past weeks of interviewing Yudin and reviewing my case notes, I was coming to the conclusion that the reason for the hikers fleeing the tent had nothing at all to do with weapons, men with guns or related conspiracies. Avalanche statistics were incredibly convincing: Nearly 80 percent of ski-related deaths were the result of avalanches. Wasn’t it the likeliest theory, after all? I imagined how the hikers would have heard the terrifying rumble of unsettled snow above their campsite, and would have fled from their tent in panic. But once they were outside in subzero air with a fierce wind pushing them down the slope, the elements had done the rest. Were all my efforts really leading to the simplest explanation of all? Until we were on the slope itself, there was little for me to do but focus on the journey ahead and on our next stop: Serov.

Kuntsevich told me that we were the first hikers to be following the Dyatlov party’s itinerary, and the first to visit the school in Serov for that purpose. But because we had no address for the school—we knew only that in 1959 it bore the name School #41—it would not be easy to find. To make things trickier, Igor and his friends had stayed in Serov the entire day, whereas our stop would be only ninety minutes.

I felt a nap coming on and claimed one of the bunk beds. My companions did the same. Before I fell asleep, I turned to the window and was reminded of the diary entry Zina had written on

their first night on the train—something about the Ural Mountains looming in the distance. And then there was her final question of the night: “I wonder what awaits us on this hike? Will anything new happen?” The thick air of the car finally put me to sleep. But the slow heartbeat of the train kept my slumber fitful as we drew ever closer to the place where Zina’s diary entries had come to an end.

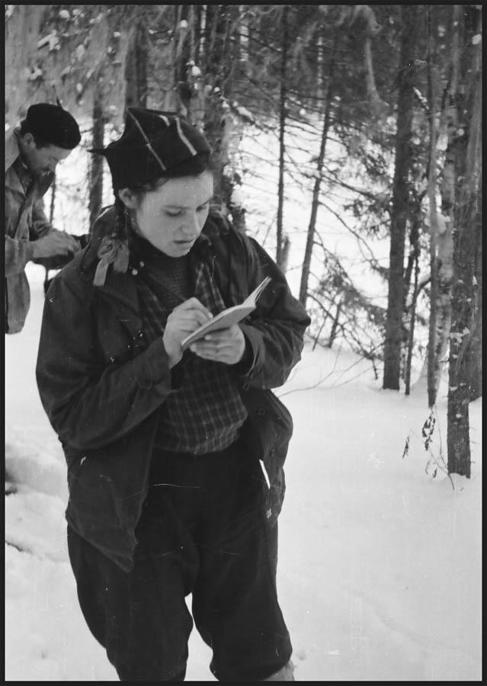

Zinaida “Zina” Kolmogorova writes in her diary, Auspiya River, January 29, 1959.

18

JANUARY 28–FEBRUARY 1, 1959

AFTER THEY WATCHED THEIR AILING FRIEND RECEDE WITH

Grandpa Slava and his horse down the Lozva, the remaining nine hikers turned in the opposite direction and continued their trek upriver. Their path over the next few days would cleave to the rivers—first the Lozva, and then the adjoining Auspiya, which they would follow north toward Otorten Mountain. Their second day on the Lozva was not all that different from the first, and they progressed over the snow-covered ice in determined silence. But because Yuri Yudin was now gone, only the film in their cameras and the pages of their diaries could bear witness to these final days of their journey.

When the path through the snow became particularly punishing, the friends would alternate taking the lead, with each shift as leader lasting ten minutes. Besides that, they had to pause every so often to scrape congealed snow from the bottoms of their skis. Where the ice on the river became dangerously thin, or where the water leached through, the skiers were forced onto the riverbank. But when the bank was too steep, or covered in jagged patches of basalt, they were forced to choose the lesser danger: fragile ice or treacherous terrain.

Their progress became considerably easier when they happened upon an existing path made by skis and reindeer hooves, the telltale

sign of Mansi hunters. There were also Mansi symbols painted on the trees along their route, as described in the group’s diary:

[The symbols] are kinds of forest stories. The marks describe animals noticed, stand sites, various indicators, and decoding those marks would be of great interest both to hikers and to historians

.

In the evenings, each member of the group had his or her assigned task in setting up camp before they were allowed to gather by the stove for dinner. As on previous nights, there was music and passionate discussion. Kolya described the group’s first night in the tent:

After dinner, we sit a long time by the fire, singing sincere songs. Zina even tries to learn playing mandolin under the guidance of our chief musician Rustemka. Then discussion goes on and on, and almost all our discussions these days deal with love

.

When the friends became sleepy, they couldn’t come to an agreement about who should lie next to the stove. An outsider might have assumed that a spot nearest the source of warmth would be the most coveted. But according to Kolya’s diary, the portable stove that divided the tent was “blazing.” While he and Zina occupied the area farthest from it, Georgy and Kolevatov were persuaded to sleep on either side of it.

[Georgy] lay for about two minutes, then he could not stand it anymore and retreated to the far end of the tent cursing terribly and blaming us for treachery. After that, we stayed awake for a long time, arguing about something, but finally it went still

.

The next day was less eventful, and after hours of making their way up the second river, their group diary had little to say:

Carved tree with painted Mansi symbols. The first three slashes represent the number of hunters in the group. The second symbol represents the family sign and the third set of slashes represents the number of dogs in the Mansi group, January 29, 1959.