Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (4 page)

Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

A previous group hiking tour with Zinaida “Zina” Kolmogorova (fourth from right with round white sunglasses), n.d.

In addition to Lyuda’s reputation as an outspoken and highly principled student, she was a fervent communist. Had she been wearing a uniform, one might have imagined she’d stepped off a Communist propaganda poster. In fact, there was a name in the USSR for such young women—“the girl in a red kerchief with a gun.”

On that evening, Yuri Yudin—one of three Yuris in the group—busied himself with packing the medicine kit. With his boyish face and a set of pronounced teeth that erupted from his mouth whenever he smiled, the geology student was the image of ease and good humor. Having suffered lifelong problems with rheumatism, a heart condition, and chronic knee and back pain, Yudin was also the least likely member of the group. He had previously been forced to take a year off from school due to an illness, but hiking had restored his vitality. Given his recurring struggles with his health, his role as the keeper of the medicine was certainly fitting.

Besides Igor, Zina, Lyuda and Yudin, there were five others: Yuri Doroshenko—“Doroshenko”—studied radio engineering at UPI with Zina and Igor. He was impulsive and brave, and carried an aura of myth about him, maybe because of the time he chased off a bear on a camping trip with nothing more than his nerve and a geologist’s hammer.

Yuri Krivonishchenko—“Georgy”—was the group’s resident jester and musician, always ready with wisecracks and a mandolin. He had a big personality and a talent for storytelling, prompting one friend to dub him “Zina with pants.” When Georgy wasn’t singing or pulling pranks, he was a student of construction and hydraulics.

Alexander Kolevatov—“Kolevatov”—was a methodical young man with an imposing physical presence. In his downtime from studying nuclear physics, he loved to puff on his antique pipe. He was also an intensely private person and often reluctant to share his journal entries with his comrades.

Yuri Doroshenko (top row, far right), Zinaida “Zina” Kolmogorova (second row, far right), and Yuri Blinov (bottom row, center), next to Igor Dyatlov, in striped cap, on a hiking tour, May 1, 1957.

Rustem Slobodin—“Rustik”—could be called the group’s rich kid. He was the son of affluent university professors, and had already earned a degree in mechanical engineering. Like Georgy, he was musically gifted and enjoyed playing mandolin. Though one might have expected him to possess an elitist air, Rustik was as unpretentious and friendly as they come.

And, lastly, there was Nikolay Thibault-Brignoles—“Kolya”—distinguished by his foreign name and background. He was the great-grandson of a Frenchman who had immigrated to Russia in the 1880s to work in the Ural factories. Kolya had already earned his degree, in industrial civil construction. Though serious and exceedingly well read, he always looked for the humor in any situation.

These seven men and two women, stooped under the weight of their packs and in a nervous bundle of excitement, left room 531 and descended the four flights of stairs. After piling out of the building and into the sharp January chill, they headed for the tram

that would take them to the train station a few miles from campus. Twenty minutes later, when the tram arrived at the station, the friends realized they were cutting it close to the train’s departure. As the group made an awkward dash for the entrance, there was no time for final departing glances over their dark, sooty town.

The nine companions found their way to their

platzkart

, or third-class compartment. Employing a popular scheme of Russian students traveling on a budget, the group had deliberately purchased fewer tickets than they needed. In the event that the conductor passed through their car to punch tickets, a couple of the hikers would hide under their wooden seats. Lyuda was particularly adept at this maneuver, and over the course of the trip, she would take advantage of her compact size to evade the conductor’s watchful eye.

As the group settled in, they noticed that their numbers had suddenly increased by one. There was a newcomer in their midst—an acquaintance of Igor’s who had asked to tag along at the last minute. As eight pairs of eyes settled on and assessed Alexander Zolotaryov, it was apparent to everyone that he was old. Well,

older

—thirty-seven, to be exact. Igor introduced him to the others, explaining that Zolotaryov was a local hiking instructor and a valuable addition to the team. Zolotaryov had originally intended to set off with student hiker Sergey Sogrin and his group, who were headed further north into the subpolar Urals, but when Sogrin’s timetable didn’t suit Zolotaryov, Sogrin introduced him to Igor. The timing was perfect, as another hiker, Nikolay Popov, had recently dropped out of Igor’s party.

“Just call me Sasha,” the newcomer told them with a flash of gold teeth. Besides having a mouth full of metal, Sasha also had several tattoos. The name Gena had been inked on the back of his right hand, and when he pushed up his sleeves, a picture of beets could be glimpsed on his right forearm. Tattoos were relatively unusual for the average Russian citizen in 1959, but they were common among veterans. Sasha had, in fact, seen combat in World War II.

After the initial surprise of finding a stranger among them subsided, the friends relaxed into their seats and chatted with the hiking groups around them. Igor and the others were happy to discover that one of their hiking-club friends, Yuri Blinov, was seated in their train car. Blinov’s party was taking the same route north to Ivdel, and the two groups would be able to keep each other company over the coming days.

The Dyatlov group’s departure may not have gone as smoothly as they’d hoped, but as the train pulled out of the station, the friends’ very best selves emerged. It wasn’t long before they embraced the company of the outsider. And when Georgy produced his mandolin, and Sasha began to sing, it was as if he had been one of them all along. The ten friends sang for hours. The group’s favorite was “The Globe,” a song about the joys of travel.

Our voices will carry on

Over mountain ridges and peaks,

Over February blizzards and storms,

Over vast expanses of snow

.

We will hear each other’s song

Though hundreds of miles lie between us,

Though far from each other we roam,

Friends’ singing will beat the distance

.

Hours later, after they had sung through and committed their new melodies to memory, Zina pulled out her diary and scribbled her final thoughts for the day.

I wonder what awaits us in this hike? Will anything new happen? Oh yes, the boys have given a solemn oath not to smoke through the whole trip. I wonder how strong their willpower is, will they manage without cigarettes? We are going to sleep, and Ural woods loom behind the windows

.

Ural Polytechnic Institute, 1959.

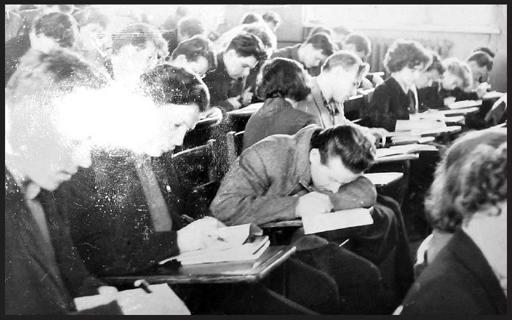

Igor Dyatlov, at far left, in class, n.d.

3

FEBRUARY 1959

ON THE EASTERN SIDE OF THE URAL MOUNTAINS, 1,036

miles from Moscow, lies Yekaterinburg, Russia’s fourth largest city and home of the Ural Polytechnic Institute. It is a gray, industrial settlement positioned at the edge of fertile wetlands; beyond it looms the startling and seemingly endless beauty of the mountains. The city’s population of 779,000 is surrounded on all sides by a thick blanket of evergreen, interrupted by pockets of swampland, ink-black lakes and quiet villages. It is a pristine setting for such a hardened town—one known for its machine and military hardware factories—and the contrast between the surrounding natural beauty and the city’s industrial grime is striking. Yekaterinburg enjoys balmy weather for half of the year, but the other half finds its streets blanketed in discolored snow and its skies darkened with cumulus gusts of factory smoke. At least, this is how the city could be characterized in 1959, when it was known by its Soviet name, Sverdlovsk.

As part of the Soviets’ drastic renunciation of monarchic rule—and, by association, the country’s Westernization by Peter the Great two centuries earlier—cities such as Yekaterinburg had undergone a kind of rechristening, if an atheistic one. In the mid-1920s, it seemed that every city was getting a new name—most famously, Petrograd (formerly St. Petersburg) became Leningrad, and the city of Volgograd became Stalingrad. But all the name-changing in

Russia couldn’t chase Peter the Great’s heritage from the country or from Yekaterinburg—a city named for the ruler’s wife, Catherine. Peter’s architectural influence can still be seen in the city’s neoclassical buildings and in the intense pride its inhabitants take in their educational institutions. Perhaps the finest of these is the Ural State Technical University, known for much of its life as the Ural Polytechnic Institute, or UPI.

In 1959, UPI—along with many of the educational institutions in the Soviet Union—was experiencing a kind of renaissance. Khrushchev had taken office a few years earlier with aims to alleviate the cultural suppression of the Stalin years. His reforms resulted in a rapid flowering of the arts, sciences and athletics—a nationwide post-Stalinist softening known as “the Thaw.” For artists and intellectuals, the Khrushchev years were badly needed irrigation after decades of cultural drought.

“Few men in history have had such long and devastating effects—and not only on their own countries but on the whole world as a whole—[as Stalin],” writes Robert Conquest in the introduction to his definitive study of the Russian leader,

Stalin: Breaker of Nations

. “For two whole generations Stalin’s heritage has lain heavy on the chests of a dozen nations, and the threat of it has loomed over all the others, in the fearful possibility of nuclear war. Stalin, to whom the aura of death clings so strongly, is himself only now ceasing to live on in the system he created. When he died in 1953 he left a monster whose own death throes are not yet over, more than a generation later.”

Even so, after Stalin’s death, intellectual society opened up for the first time since the Bolshevik Revolution, resulting in more freedoms and opportunities for everyday people. This heady and short-lived period in Russian history was particularly liberating for those who had survived the devastating losses of World War II and, before that, the punishing show trials of the ’30s—famously

fictionalized in Arthur Koestler’s novel

Darkness at Noon

—during which Stalin had imprisoned and murdered perceived political rivals.