Read Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident Online

Authors: Donnie Eichar

Dead Mountain: The Untold True Story of the Dyatlov Pass Incident (9 page)

After the disruption resolved itself, the hikers were left most vividly with the impression of the classroom they had visited that day—and the love the schoolchildren had so readily given them.

Weeks later, once School #41 had gotten word that the Dyatlov group was missing, the children all wrote letters to UPI, expressing their concern and asking the frank questions that children ask.

What happened to their new friends? Where was Zina?

But their mail went unanswered, even after the group’s fate was known. Yuri Yudin received one such letter from a child they had met that day, but he didn’t have the heart to write back. What could he say?

6

FEBRUARY 1959

ON FEBRUARY 20, THE SAME DAY A SEARCH HELICOPTER

is dispatched from Sverdlovsk, the Ivdel prosecutor’s office orders a criminal investigation into the case of the missing hikers. There is nothing yet criminal to investigate, but the purview of the office goes beyond the strictly criminal. The regional prosecutor, Nikolay Klinov, assigns prosecutor Vasily Tempalov to head up the investigation, most likely because Tempalov’s Ivdel office is closest to where the hikers were last seen. Tempalov holds the title of junior counselor of justice—the equivalent rank of major in the army—and though at thirty-eight years he is relatively young, he has considerable experience prosecuting cases in the region. He has zero experience, however, with young hikers gone missing, and until the searchers turn up some evidence of the hikers, there is little Tempalov can do from his office.

The Sports Committee of Sverdlovsk, meanwhile, is trying to determine the hikers’ route so that they can relay the information to the search teams. Because Igor Dyatlov’s intended course was not found in the hiking commission’s files, the committee will have to track down someone acquainted with the group’s journey. Not realizing that one of the hikers, Yuri Yudin, has since returned to town, the committee turns to the only man they believe can help: Yevgeny Maslennikov, chief mechanical engineer at the local Verkh-Isetsky Metal Mill. Not only is he a distinguished UPI alumnus,

he is also one of the best backcountry skiers in the city and serves as a hiking consultant to clubs throughout the larger region of Sverdlovsk. In fact, he personally signed off on Igor Dyatlov’s proposed course into the northern Urals.

When Maslennikov receives a call from Valery Ufimtsev of the Municipal Sports Committee, he is surprised to learn that Igor and his friends have not yet returned. “I told him what I knew about their route,” Maslennikov later told investigators. “I said that the route was hard, but the group was strong; they couldn’t lose their way, and therefore the situation is critical.”

After relaying the group’s intended destination of Otorten Mountain, Maslennikov suggests to Ufimtsev that one of the hikers may have a leg injury that has slowed the entire group. Or, he speculates, they all caught the flu and are recovering in a nook somewhere. Before Maslennikov hangs up, he agrees to join the growing search efforts as an adviser. Three days later, he would himself fly to Ivdel to join the air and ground searches.

Gordo and Blinov, meanwhile, have been unsuccessful in their attempts to pick up the hikers’ trail leading from Bahtiyarova village. By the estimates of Mansi villagers, the hikers had arrived approximately sixteen days earlier, putting their visit around February 4.

On February 23, the day after Gordo and Blinov visit the village, several Mansi tribesmen join the search effort. Their help is essential, as the Mansi know these mountains intimately. The group is headed by Stepan Kurikov, who, despite his Russian name, is a respected elder of his people. It is not unusual for the partially assimilated Mansi to take Russian names.

By now the search teams have arranged for radiograms to be sent back to Ivdel and Sverdlovsk. The radio is heavy and requires skilled operators, but this wireless form of communication is the only way to send messages rapidly between the mountains and the city hundreds of miles away. The first radiogram reads:

MANSI AGREE TO JOIN SEARCH

DAILY PAYMENT FOR 4 MEN 500 RUBLES

MANSI FOUND TRACKS 90 KM FROM SUYEVATPAUL TOWARD URAL RIDGE

GIVE PERMISSION FOR SEARCH

/BARANOV/

Upon Maslennikov’s arrival in Ivdel on February 24, there is a noticeable escalation in the search efforts. The same day, the Ivdel municipality agrees to a search of all possible routes the Dyatlov group may have taken. In addition to continued aerial sweeps, there are new boots hitting the ground, among them UPI students, family members, local officials and volunteers from the surrounding work camps. Over the next few days, nearly thirty searchers fan out over the snowy topography, targeting the Vishera River in the Perm region, Otorten Mountain itself, the Auspiya River valley, and the surrounding areas of Oyko-Chakur and Sampal-Chahl.

A search by helicopter over the Auspiya River is quick to pick up ski tracks along the bank. Groups on the ground, meanwhile, follow up on the discovery of Mansi hunters that ski tracks and evidence of camping were spotted 55 miles from the Mansi village of Suyevatpaul. In response to the latter, a group headed by the Mansi team’s Stepan Kurikov, accompanied by a radio operator, sets out in the direction of the ski path. In anticipation of finding the hikers at the end of these tracks, they equip themselves with a first aid kit and food.

By the next day, however, there is still no immediate sign of the hikers. One of the groups, headed by UPI student Boris Slobtsov, is searching the Lozva River valley when a message drops to them from overhead. Aerial note-dropping is a common form of communication, particularly in remote areas where radio transmission is difficult or impossible. The communication can work both ways. For the searchers to relay to airplane or helicopter pilots that everything is fine, two people lie parallel in the snow. To indicate the direction they are headed, four people form the shape of an arrow. If a message needs to be communicated to searchers on the ground, a note is attached to a brightly colored object, often red, which flaps visibly on its descent.

Helicopter search for the hikers, February 1959.

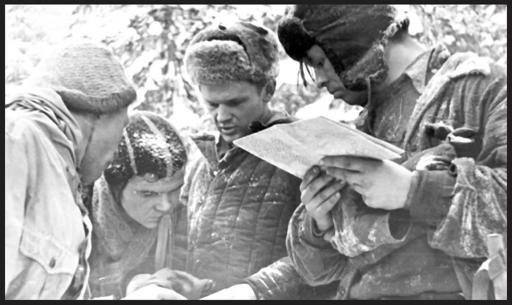

Members of the search team gather to strategize. (From left to right: Mikhail Sharavin, Vladimir Strelnikov, Boris Slobtsov and Valery Khalezov.) Photo taken by Vadim Brusnitsyn, February 1959.

The note dropped to Boris Slobtsov on February 25 instructs the party to alter its route and begin searching along a smaller adjacent river, the Auspiya, where ski tracks were recently spotted. Slobtsov and his team of nine promptly change course and that same day pick up not only on the Dyatlov ski trail, but also evidence of one of their campsites along the river.

Boris Slobtsov is not a trained searcher, nor is anyone else in his group. He is twenty-two years old, in his third year of studies at UPI and is a member of the hiking club. He not only admires Igor Dyatlov as a fellow hiker, but also considers him a friend. If something like this could happen to someone as capable as Dyatlov, it could happen to any one of them. It was a fellow hiker’s duty to help in any way that he could.

Slobtsov’s group sets up camp that night in the protection of the neighboring forest, planning to reconnect with the ski tracks the next day. The next morning, however, as they resume their course along the river, Slobtsov and his crew are unable to pick up the trail. The wind that day is strong, and it is easy to imagine that the tracks have simply blown away. The wind is so fierce in this region, Slobtsov notes, that the straps on his ski poles often lie parallel to the ground. With no trail to follow, the searchers have no choice but to continue along the river.

One of the searchers in his group, a volunteer named Ivan, complains of feeling ill and informs Slobtsov that he will be turning back to Ivdel. Though the group believes he isn’t sick at all, only scared, they agree to go on without him. Before Ivan leaves, he suggests that the group continue in the direction of Otorten Mountain until they encounter a streambed at the bottom of a slope. Because of the westerly wind in this area, he says, the snow has accumulated along the slope, creating potential avalanche conditions. The possibility that Dyatlov and his friends have gotten buried in snow is not one Slobtsov wants to believe, but after the group says good-bye to Ivan, they take his advice and head in the direction of the mountain. To increase their chances of success, Slobtsov suggests the team break into pairs, with Slobtsov taking classmate and hiking-club member Mikhail Sharavin. From the Auspiya River, Slobtsov and Sharavin head up the slope, hoping to get a better view from the hill overlooking the riverbed. By now, the weather is worsening and their time is limited.

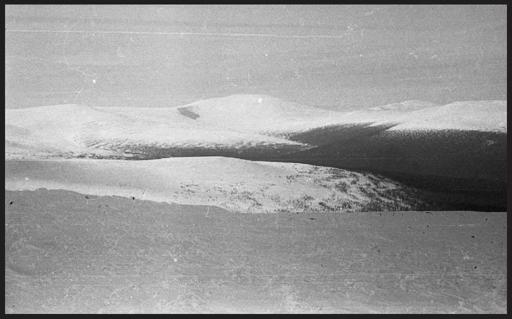

Otorten Mountain, the destination of the Dyatlov hikers. Photograph taken by the rescue team, February 1959.

At some point in the afternoon, before they are able to reach the crest of the hill, Sharavin sees something that makes his pulse quicken. “About seventy meters to our left,” Sharavin remembered later, “I noticed a black spot that was actually part of a tent.”

Sharavin alerts Slobtsov, and the young men hurry toward the spot as quickly as the wind and deep snow will allow them. The tent’s poles are still vertical, with the south-facing entrance still standing. But recent snowfall has covered much of the tarpaulin, causing part of it to collapse—though it is not immediately clear whether this is the result of a storm, or of wind redistributing the surrounding snow. The men call out but receive no answer. There is an ice ax near the front of the tent, sticking out of the snow. There is also a partially buried Chinese torch, left in the on position. Sharavin retrieves the ax. He swings it behind him and brings it forward to rip open the tent.