Death at the Alma Mater (2 page)

Read Death at the Alma Mater Online

Authors: G. M. Malliet

Tags: #soft-boiled, #mystery, #murder mystery, #fiction, #cozy, #amateur sleuth, #mystery novels, #murder

“In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree,

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.”

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Webster was much possessed by death

And saw the skull beneath the skin.

—T. S. Eliot

ALMA MATER

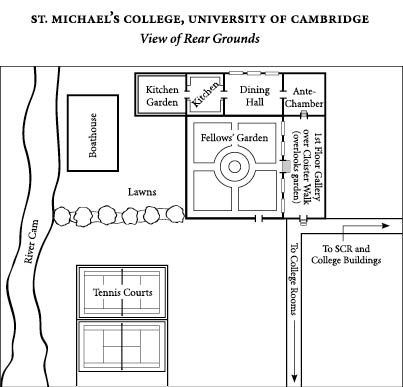

Founded around the time

King Henry VIII was selling off “his” monasteries, St. Michael’s College of the University of Cambridge spreads in haphazard fashion by the River Cam, a model of functional medieval architecture wedded to Tudor bombast and, later, Victorian excess.

The University itself, of which the college is a part, was formed by a group of tearaway scholars escaping the wrath of the townspeople of Oxford, where clashes had ended with two students being hanged for murder, which incident should have given everyone in Cambridge pause. But by this time—the early 1200s—the inhabitants of Cambridge had survived the Romans, the Saxons, the Vikings, and the Normans, and, perhaps numbed into apathy at the sight of yet more new arrivals, rashly allowed the fledgling seat of learning to take hold.

St. Mike’s, as it is inevitably called, is one of the lesser-known of thirty-two Cambridge colleges—a former Master liked to insist it was as well known as Trinity, which is like saying Marks and Spencer is as well known as Harrods—and it has never, even from its earliest days, been among the wealthiest of colleges. Indeed, it has more than once in its long history flirted with financial disaster. One early benefactor, having promised the college a substantial legacy, on the strength of which promise the college incurred various debts, was found on his death to be worth only £23

.

There were many other such incidents as the college slumbered its way through the centuries, betraying either a touching naiveté or a rampant incompetence on the part of those entrusted with St. Mike’s care.

The college was, however, given a boost in early Victorian times by an infusion of funds from the will of a wealthy owner of smoke-belching smokestacks in the Midlands. A painting of this scowling, mutton-chopped benefactor hangs, like an old-

fashioned ad for castor oil, in pride of place in the Hall—one of the conditions of his bequest. But this benefactor’s funds, too, had long since gone to repair the crumbling brick and clunch of the chapel, and by the late 1980s exuberant but doubtful investments in the stock market and offshore hedge funds had shrunk the college’s coffers still further. The stone walls, chipped in places and worn to a gloss in others, continued to flake and wear like a favored old coffee mug, and the college remained a constant source of anxiety for the Bursar and others in whose care she was entrusted. (Although named for a male saint, St. Michael’s is female, as are all the colleges, and a high-maintenance female, at that.)

So it was that as the twentieth century neared a close, the then-Master decreed “Something Must Be Done,” and the answer came back from the Senior Combination Room, as it had done since time immemorial: “Let’s hit up the old members for donations.”

Something resembling energy infused the normally antebellum spirit of the SCR. Brochures were produced on one of the college’s antique computers, and pleas personally signed by the Master were mailed out by the hundreds. This campaign met with little success (a thunderous silence, in fact), so much so that the suggestion of one wag—that the fundraising brochure be illustrated by a photo of a starving student holding a tin cup—was taken under serious consideration for as long as two weeks. Finally another idea was broached: Why not tempt graduates back to the college during the summer for a St. Mike’s Open Weekend? The initial thought was that college members of specific years of matriculation would be invited, but over time it became the custom to carefully screen the guest list to include only the most successful—in monetary terms, that is—graduates. (One weekend in 1991 creative artists spawned by St. Mike’s were invited, an experiment that was never to be repeated, as the artists proved not only to be living in less-than-genteel poverty, but to have accepted the invitation in the hope of being offered stipended Fellowships. They ended up alleviating their disappointment by making chip shots on the college’s manicured lawns and dressing the statue of the College’s Founder in women’s undergarments. One specialist in “Found Art” left behind in his room a large tortoise. The hysterical bedder who discovered it was instrumental in instituting the ban on artists’ weekends at St. Mike’s. A specialist in tortoise biology easily being located—this was Cambridge, after all—the tortoise was duly adopted and lived to a ripe age somewhere in the region of North Piddle.)

The Bursar was generally assigned the task of combing through the lists of members who, for good or ill, had made their mark on the world, and had been well compensated for the marking up. He gradually began to notice that 1988 had been a bonanza year for such luminaries at the college—that over the course of the past twenty or so years, several of the members who had matriculated or were in some way attached to the college in that year had achieved success and, more to the Bursar’s purposes, accumulated great wealth. It seems 1988 was one of those times, not unlike the Renaissance, perhaps, when the world burst with new ideas and energy before subsiding once more into its habitual indolence. In any event, the Bursar soon had a short list of worthies—the Master had asked that the gatherings be kept to under ten members, since spouses and guests were also encouraged to attend—and the college Fellows were duly summoned to hear the announcement concerning the upcoming festivities, to which most of them would not be invited.

(“Good Lord, the idea is to get the old members to donate, not to revive any horrid lingering memories they may be harboring of the place,” the Master had been heard to say. “No, the Fellows must be told in no uncertain terms: They are to stay away from the visitors unless instructed otherwise.”)

Over the years, a regular program had evolved to keep the targeted visitors suitably entertained. They would be invited to partake of a dinner on a Friday and a special buffet lunch in the Master’s Lodge on a Saturday, with a tea that afternoon and a Choral Evensong followed by a formal dinner in Hall, watched over by the portraits of the colleges’ Masters down through the years (portraits which had gotten bigger and bigger in an unspoken competition for Most Beloved and Important, so that the march of centuries, if not progress, was easy to trace). On Sunday would be a Sung Eucharist in the Chapel. As a special treat, the Library and College Gardens would be flung open, with lectures offered by the College Archivist and the Head Gardener, and an exhibition of College Silver would be mounted in the Senior Combination Room. An added highlight—a veritable pièce de résistance—was a tour of select student rooms, all carefully purged beforehand of traces of graffiti, scraps of unwashed clothing, seminal Marxist tracts, and empty liquor bottles.

In short, it always promised to be a weekend of the most stupendous dullness for any but the most steadfast and loyal alumnus or alumna, but in fact it proved over the years a surprisingly popular and successful venture, especially among the Americans, especially once a tasting of the College wines was added to the program. The Secretary of the College Wine Committee, an attractive man with a gift for smooth repartee, was on hand to answer questions on these occasions, where cases of College port and sherry were offered for sale, with free shipping thrown in for the Americans.

If all went according to plan, purse strings (and tongues) would be loosened, and the coffers of St. Mike’s would once more fill to overflowing.

This, in any event, was the plan, a plan that had been successful, in varying degrees, for many long years. It has since been largely agreed that no one could have foretold the calamitous events which took place during the particular reunion that is the subject of this story.

No one, after all, had ever suggested that the alumni of St. Mike’s be invited back for a murder mystery weekend.

A HIVE OF ACTIVITY

It was the upcoming

Open Weekend that was the subject of a special meeting of the College Bursar and the College Dean, convened by the Master in his dark, Tudorish study one unseasonably warm evening in late June. The wealthy graduates were due to start arriving on July 4, and despite problems with the antique plumbing that had prompted some last-minute rearrangements and tested the bedders’ patience, everything looked set for a memorable weekend—more memorable, as has been mentioned, than anyone could have anticipated.

There was a general bustle of activity as the three settled in their accustomed places. The Master, having surveyed his small assembly with his habitual look of contempt, took his own seat at the head of the rectangular table, first flinging aside imaginary swallowtails like a concert pianist. He then offered his brethren a wintry smile, folded his hands in his lap, and turned with a nod in the general direction of the Bursar.

Ten minutes later, a student with the cheek to peer in through the mullioned windows of the study would have seen that the Bursar was just reaching the end of a list of projected events.

“Let’s see now. Croquet set up on the lawn. Tennis courts and equipment made available. Yes, I think that’s it for the sporting activities. If they want to hire a punt they can easily walk into town. We could offer them access to the sculls …”

“They’re getting too old for that, although they won’t think so,” said the Master, a man long-boned, pale, and gray, like something thrown up on the tide. He was the kind of person who even if forced into jogging togs would manage to look as if he were wearing a suit and tie. He had a wife, rumored to be sickly. She was seldom trotted out, looking when she was like a spouse at the press conference of a politician who has just been caught in a prostitution ring, appearing dazed and disoriented as if shot through with tranquilizer darts.

“It’s a young person’s sport. I’ll not have the weekend spoiled by the sound of rescue sirens piercing the night air,” continued the Master.

The Dean—the Reverend Otis—nodded his agreement, the overhead light glinting on his polished head and setting his dandelion hair aglow, giving him a halo of sorts.

“No, indeed. We wouldn’t want sirens to spoil the fun,” he said in his earnest way. “Will there again be a tour of the Gardens following Wilton’s lecture? I do so enjoy that.” He tapped fingertips together in a happy little pitty-pat of anticipation. He was a man who talked slowly and with extreme care, searching for each word, examining each thought before releasing it dove-like into the air. “Like a man with a bullet lodged in his head,” the Master had been heard to say, most unkindly, behind his back.

Ignoring him, the Master again turned small, watery eyes the color of tarnished silver on the Bursar.

“The dining arrangements?” he asked.

“Yes.” The Bursar flipped open a new folder. This one was red to signal its importance. “Afternoon tea in the garden of the Master’s Lodge, weather permitting … a four-course dinner with wine in Hall at eight p.m. on Saturday accompanied by musical entertainment provided by our more talented undergraduates” (“When you find some, just be sure they’re told to be well out of the room before pudding is served,” the Master interjected. “One can never know how they’ll behave.”) “… followed by a gathering for port, chocolates, and coffee in the Senior Combination Room. I say,” the Bursar looked up from his spreadsheet, “do we have to give them chocolates? This is getting rather expensive.” The Bursar, true to his calling and training, was a man with a keen eye for the bottom line.

“Yes, Mr. Bowles, we do. Belgian chocolates.” The Bursar’s hand flew to his mouth to stem a cry of horror. He had been planning, as the Master had rightly surmised, to fob the guests off with something from the Christmas sale bin at Sainsbury’s. “This is no time to be penny wise,” continued the Master.

“‘And is there honey still for tea?’” quoted the Reverend Otis.

“No!” said the Bursar, nearly shouting.

“We’re going to be asking these people for donations in the hundreds of thousands of pounds,” said the Master. “We’re frightfully lucky to have alumni who have done so well for themselves.”

He added this last sentence grudgingly, for the Master, who was a tremendous snob, was also extremely sensitive to the fact that St. Mike’s was a college so small and obscure as to be invisible in the pantheon of notable Oxbridge colleges. He longed to be Master of a college in the grand tradition, to be able to boast of famous scientists and diarists nurtured upon the college’s bosom, but it was not to be. Neither a Nobel laureate nor an Archbishop of Canterbury had ever swollen the college’s ranks. Not even a prime minister. St. Mike’s, although hundreds of years old, at the darker moments of its history had been remarkable only in that so many third-rate minds had managed to assemble under one roof.

When the Master looked at the competition—Peterhouse, founded 1284; Queens’, 1448; St. John’s, 1511—it was with the sinking sense of inevitability that however many centuries St. Michael’s was in existence, and even if it one day managed to produce a Nobel Prize winner or two, it would never belong truly in the lineup of really old, really famous colleges. Even at two thousand years of age, it would remain young and somehow, forever, not quite the done thing.

Somehow this train of thought led him to face another anxiety that had been niggling at the corners of his mind for some time.

“That old business of the scandal,” he began. “I’m a bit concerned, you know.”

“Quite,” said the Bursar, catching him up immediately. “When I saw how the guest list was shaping up, I did wonder whether …” As noted earlier, the Bursar, tasked with providing a list of candidates suitable for a genteel shakedown, had realized the students living in college in 1988 had turned out to be a remarkably successful lot. So he had subtly altered his usual methods of assembling his list: Those invited for this particular Open Weekend had not necessarily matriculated in the same year and were in fact a collection of former graduate and undergraduate students of varying ages.

“That kind of thing can’t be encouraged,” said the Master.

“Not for one single moment. No indeed,” said the Bursar.

All of this was moving right past the Dean, like leaves scattering before a gentle breeze.

“Scandal?” he said, his gentle eyes wide. “I don’t recall anything like that.”

The Master was not surprised. There could be nightly orgies and Black Masses on the High Table and the Reverend Otis, almost childish in his innocence, would be the last to notice, or to understand what was transpiring if he did notice.

He gave the Dean a shriveling glance and said, “Well, you were here at the time, and they made little secret of it. It’s incredible that even you didn’t notice the drama.”

Typically, the Dean took no offense at the “even you.”

“Let’s see. The year 1988, you say … I think I do remember something about it now. The blonde woman, wasn’t it? Two blondes, actually—isn’t that right? It was all so long ago. Surely …” He didn’t finish the sentence. Otherworldly or not, it registered with the Dean that having all the players in such a story under one roof might make for an uncomfortable time, at least for some. Determined, as always, to put the best face on things, he continued, “Surely all is long forgiven now.”

The Master and the Bursar wiggled raised eyebrows at one another over the Dean’s head. Everyone except the Master held the Dean in the highest regard but he was without question the most useless Fellow about the place.

The Master said, “Even without that particular complication, I do so hope there won’t be any friction. These old boys—and now, of course, girls,” he added, mournfully, placing an emphasis of distaste on the word. He was one of the old school that remained unreconciled to the admission of women to Cambridge. He might have been discussing an infestation of mice. “These old-boys’ get-togethers … I do wish we didn’t have to be bothered, really—bound to be trouble, however minor.”

“Why do you say so, Master?” asked the Reverend Otis, again wide eyed, this time at the thought that anyone would choose strife when peace was such an easy alternative.

“Because,” the Master replied with exaggerated patience, knowing it was breath wasted, “only a certain type is drawn to these weekend reunion events, don’t you see? People with something to prove, people with something—whether a spouse or a car—to show off, people with …” His voice trailed off.

“With?” prompted the Bursar.

The Master had been about to say, “People with a score to settle.” The thought had emerged in his mind full blown, unbidden. Uncomfortable thought. Thank God he had not spoken it aloud. The Bursar was a solid man, if a bit excitable at times. As for the Dean, well … The Dean had been born to demonstrate the meaning of the word “suggestible.”

“Nothing, nothing,” the Master said now. “I do rather wish the whole thing were over and done with this time, I must say.”

“Soon enough,” said the Dean beaming on him kindly. “Soon enough.”