Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (16 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

The Polish capital had come within Richthofen’s zone of operation during the first week of the campaign, when Reichenau neared the city from the southwest. A firm believer in the terror raid since his days in Spain, Richthofen ordered Colonel Seybold, the commander of the 77th Bomber Wing, to bomb the ghetto area of Warsaw. Seybold, however, had scruples against attacking defenseless civilian targets. The next day, September 11, he disobeyed orders and “on his own authority and in agreement with his sub-commanders . . . diverted the group designated for this attack to targets of military importance in Warsaw.” Furious, Richthofen relieved Seybold of his command, effectively ruining his military career.

19

The tenor raid on Warsaw had to be postponed indefinitely, however, because a nervous Goering began to withdraw the He-111s to the western front the next day. Once again, Richthofen was very angry: he wanted to use the bombers to drop flambos on Warsaw.

20

| |

| TABLE 6: UNITS ASSIGNED TO FLIEGERFUEHRER Z. B. V. (RICHTHOFEN), SEPTEMBER 3-30, 1939 | |

| Date(s) | Units |

| 3-4 Sept. | II/StG 2 |

| 4 Sept. | I Battalion, 23rd Flak Regiment * |

| 6 Sept. | HQ, LG 2, controlling two Stuka groups |

| 8 Sept. | StG 77 |

| III/KG 51 | |

| 9 Sept. | II and IWKG 77 |

| 11 Sept. | I/StG 1 |

| 11-16 Sept. | III Battalion, 1st Parachute Regiment * |

| 14-15 Sept. | I Battalion, 3rd Flak Regiment * |

| 20 Sept. | I/KG 77 |

| 22-30 Sept. | I/ZG 76 |

| I/LG 2 (Me-110s) | |

| I/JG 76 | |

| 23-26 Sept. | IV/KG 1 (Ju-52s) |

| 24 Sept. | IV/LG 2 (Stukas) |

|

*

For airfield protection.

Source: Speidel MS.

By September 22 Warsaw was tightly invested by the Third and Eighth Armies, and Richthofen was again calling for an all-out annihilating terror raid against the city. His recommendation was turned down, but when Polish resistance showed no signs of slackening, OKL approved the raid.

Richthofen struck the Polish capital at 8

A

.

M

. with 1,150 airplanes. Eleven percent of the bombs that fell were incendiaries. They were dropped by thirty Ju-52 transports. Two men in each plane hurled the two-pound fire bombs out of the cargo door with ordinary potato shovels. The fires which resulted caused such dense clouds of smoke that it was impossible for German observers to identify any detail in the city, either by ground or aerial observation. The aiming of the bombs was extremely inaccurate, of course, and some fell within German lines, causing friendly casualties.

General Blaskowitz was furious. He quickly called Richthofen to account, but the baron refused to call off the raid just because German soldiers were being killed. Their argument reached such proportions that Hitler himself had to be called in. At the joint Army-Luftwaffe Command Post the Fuehrer ruled that the Luftwaffe was to operate as before. Special Purposes Air Command flew 1,776 sorties against the city and pulverized it with 560 tons of high-explosive bombs and 72 tons of incendiaries. Smoke clouds over Warsaw reached heights of 18,000 feet. That night the glow from the burning city could be seen for miles—all quarters of the city were on fire. All the Germans lost was two Stukas and a Ju-52, shot down by Polish antiaircraft fire.

The next morning Richthofen was told that the Luftwaffe was to operate against Warsaw only at the direct request of the Eighth Army. Apparently these orders came directly from Goering. No such request was forthcoming from the disgusted Blaskowitz, so Richthofen, on his own initiative, attacked the nearby city of Modlin with 450 aircraft. He was preparing to raid Warsaw again on September 27, when white flags appeared. Polish General Juliusz Rommel surrendered the city unconditionally, so Richthofen attacked Modlin again, this time with 550 aircraft. Rather than endure such an attack again, the city surrendered later that day. All totalled, Richthofen had dropped 318 tons of bombs on the city on September 26 and 27.

The last seat of Polish resistance, the naval base at Hela, surrendered on October 1, and the last sporadic resistance ended on the 6th. The campaign had lasted thirty-six days, during which the Polish army of more than a million men had been completely destroyed. The Luftwaffe had lost only 285 aircraft during the campaign and was, in fact, stronger at the end of the battle than when it began. The lion’s share of the credit for the victory went to the two new arms of the German armed forces: the panzer branch and the Luftwaffe. For the first time in history an air force, operating as an independent service, had played a decisive role in a ground campaign. The Luftwaffe leadership’s mood was euphoric. Their arm had come through its first trial of combat with flying colors, and it seemed to be invincible. In their eyes—and in the eyes of the world—it was, at least for the moment.

During the Polish campaign, the tactical air support methods Wolfram von Richthofen had perfected in Spain had been completely vindicated on a larger scale, or so it appeared to Goering, Jeschonnek, and most of the rest of the Luftwaffe. Despite his relatively junior rank, Richthofen continued to be a dominant force in the Luftwaffe, with unfortunate results. Even now no effort was being made to develop the strategic potentialities of the German Air Force.

Despite the magnitude of its success, there were a number of deficiencies in the Luftwaffe, as some of the more astute General Staff officers noted. Training was inadequate in many areas, especially in instrument flying and bomb aiming. In fact, the Luftwaffe had been built so rapidly that, prior to Poland, some of the newly formed units had never practiced with live bombs at all. General Speidel concluded: “Weaknesses were noticeable in unit commanders and all officers, because most of them lacked theoretical and practical experience.” He also wrote: “Inadequacies became apparent everywhere due to the too-speedy build-up, in which emphasis was on numbers rather than quality.”

21

It was too late to do much about it now, however; they were already in the middle of a world war.

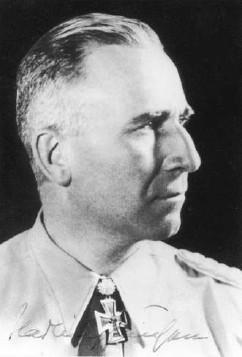

Lt. Gen. Martin Harlinghausen, the anti-shipping expert who commanded the naval air squadron of the Condor Legion and was later Air Commander Atlantic.

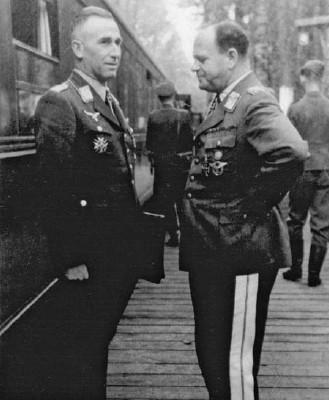

Harlinghausen (left) with Field Marshal Erhard Milch, the state secretary for aviation and deputy commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe.

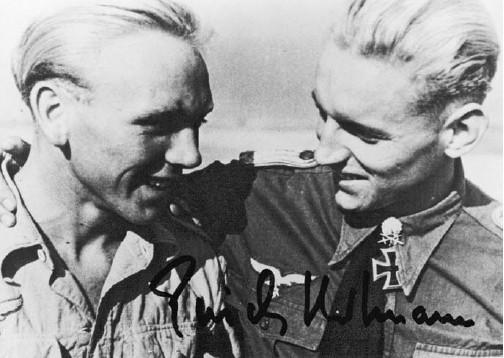

Erich Hartmann (right), who shot down the incredible total of 352 enemy airplanes. He is seen here with his rear gunner, Heinz Merten.