Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (13 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

*

Headquarters, Luftgau XI, was transferred to Hamburg on April 1, 1939.

Source: Suchenwirth MS 1969.

There was no uniform establishment for an air division. Each had at least one fighter wing and two or three bomber wings; some also had a dive-bomber wing. Eventually every division was given a long-range (strategic) reconnaissance squadron and an air signal battalion.

The Lehrdivision had grown out of the II Group, 152nd Bomber Wing, in Greifswald. It was officially formed on August 1, 1938, and by June, 1939, consisted of two training wings, a flak artillery regiment, and the Luftwaffe Signal Communications Training Regiment. The division cooperated closely with the Luftwaffe testing stations, various manufacturing firms, and the Technical Office until the outbreak of the war; then it was relieved of its training mission and sent into combat.

The 7th Air Division, which was established on June 1, 1938, included the 1st Parachute Regiment (headquartered at Stendal), the 16th Infantry Regiment (transferred from the army), and the 1st and 2nd Special Duty Bomber Wings, equipped with Ju-52 transports. The 7th Air Division was commanded by World War I ace General of Flyers Kurt Student, who was also inspector of parachute and airborne forces.

4

The propaganda machines, both of Germany and other nations, pictured the Luftwaffe in 1939 as a war machine of overwhelming strength. They did such a good job that almost fifty years have not shaken this image. In fact, the Luftwaffe had many glaring weaknesses, as the insiders on the General Staff knew. The vital question remains: did Adolf Hitler know of the Luftwaffe’s weaknesses?

According to Col. Nikolaus von Below, Hitler’s Luftwaffe adjutant, all air problems until far into the war were handled by a simple tête-à-tête between Hitler and Goering. Jeschonnek, as chief of staff, could only urge Goering to inform the Fuehrer of the true nature of the situation. Apparently Jeschonnek did not do so; and even if he did, it is certain that Goering did not tell the Fuehrer.

Would Hitler have behaved differently in 1939 if he had known that it was impossible for the Luftwaffe to annihilate the R.A.F. and wage a successful strategic air war against the United Kingdom? Would he have tried to reach a genuine understanding with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain on the Danzig issue in 1938 or 1939, instead of going to war so lightly? We will never know the answers to these questions for sure, of course, but they do point out the dangers of the Goering-Hitler relationship, which had benefited the Luftwaffe so greatly in its early years.

Despite the chaos in the Technical Office, the intriguing, backbiting, plotting, and confusion in the OKL and RLM, the inexperience in the General Staff, the general disorientation caused by a too-rapid expansion, and the lack of leadership at the top, the Luftwaffe entered World War II with an impressive array of aircraft, at least by 1939 standards.

In August 1939, there were thirteen combat-ready bomber wings in the Luftwaffe. The standard bomber was the twin-engine He-111, a medium bomber. It was manufactured at the Heinkel plant at Oranienburg, which had been designed by Albert Speer, Hitler’s favorite architect, in 1936. The first He-111 rolled off the assembly line in early 1937. It could carry 2.2 tons of bombs and had performed well in Spain. Its speed was only about 250 miles per hour, and its maximum range was only about 740 miles. Considered virtually invincible in 1937, it would be looked upon almost as a sitting duck on the western front by 1941. Nevertheless it would remain the backbone of the German bomber arm throughout the war.

5

The other major medium bomber was the Do-17, which was also used as a long-range reconnaissance aircraft. Dubbed the “Flying Pencil,” it had a 1.1-ton bomb carrying capacity. Its speed and range were similar to that of the He-111, except for the F model (the Do-17F), which had a range of nearly 1,000 miles.

Germany had no long-range bomber in 1939, although one was under development: the twin-engine Junkers 88. Udet and Milch had already informed Goering that the Luftwaffe would reach its ultimate strength of 5,000 Ju-88s in April 1943—about the time the Luftwaffe originally expected to go to war. Unfortunately, Udet and the Air General Staff had added the requirement that the Ju-88 be able to dive. As a result, its weight increased from six tons to more than twelve tons, with a corresponding decline in range and speed. Goering had proposed to Milch, Udet, and Koppenberg that the Ju-88 replace the He-111 as the standard bomber after the first prototype came off the assembly lines in September 1938. Milch opposed this move on the grounds that the air brakes and structural strengthening required to make it a dive-bomber severely cut its performance. He was overruled by Goering, who ordered Koppenberg to oversee its manufacture.

The structural, design, and technical problems which Milch pointed out came to light only after the production models came off the assembly lines in 1939. The Luftwaffe bomber program never really got back on track as a result. Although about fourteen thousand Ju-88s were manufactured by the end of the war, the bomber never achieved its full potential, due to the added weight, which cut its speed and reduced its range to about twelve hundred miles. It was still highly maneuverable, however, and was used mainly as a night fighter in the last years of the war.

Besides the glaring lack of a long-range bomber, the Luftwaffe bomber arm went into war poorly trained. It lacked night bombers, radar guidance systems, bombs larger than 1,000 pounds, modern armaments, air-to-air communications, and good bombsights. It was also short of trained commanders at every level—the natural result of a too-hasty buildup.

The Luftwaffe dive-bomber units were equipped with the Ju-87 Stukas which had done so well in the Spanish civil war. They had been adopted on the recommendation of Udet and had gone into series production in 1937. About five thousand were manufactured during the war. The vulnerability of the Stuka to modern fighters was not recognized until 1940. Only eight groups of Stukas were ready for war in August, 1939.

The most numerous airplane manufactured by Nazi Germany was the Me-109 of which 30,480 were produced between 1939 and 1945. This single-engine fighter went through several models, the most important of which was the Me-109G, which had more power than earlier models. The Me-109E was the most important fighter in the 1939–41 period. It was small, fast, climbed rapidly, and had good maneuverability. Armed with two machine guns under each wing and a 20mm machine gun which fired through the propeller hub, it was superior to anything the Poles, French, Dutch, or Belgians sent up against it. Later models had even more firepower. It was, however, slightly inferior to the British Spitfire and definitely inferior to the Hurricane.

Between 1941 and 1945 the Me-109 was gradually replaced as a fighter by the Focke-Wulf 190, but never completely. The Me-109 was also widely used as a fighter-bomber in the East, especially after 1942. In August, 1939, the Luftwaffe had five single-engine fighter wings and eighteen and one-third independent groups at its disposal. Almost all of these were equipped with Me-109s, although a few groups still flew obsolete biplanes.

The Me-109, which had a range of only 365 to 400 miles, was unsuited for the mission of escorting bombers. For this purpose the Luftwaffe adopted the Me-110, a twin-engine fighter, in 1938. When war broke out in Poland, the Luftwaffe had ten twin-engine fighter groups. Long-range and short-range reconnaissance units in 1939 were equipped with a few Do-17s and a variety of obsolete aircraft, including He-45 and H-46 biplanes. Many of these units were attached to the army during the Polish campaign. The Luftwaffe also mustered 552 tri-engine Ju-52 transports when the war began.

6

“No serious thought was entertained in intermediate or high levels of the Luftwaffe command that the war with Poland was imminent,” then-colonel Wilhelm Speidel, the chief of staff of the 1st Air Fleet, wrote after the war. “This was all the more the case because the existing weaknesses and inadequacies in the training, equipment, and operability of the field forces were too well known and were dutifully reported repeatedly to the higher levels of command.”

7

It was not until Hitler summoned the leading commanders and staff officers of the armed services to the Obersalzberg on August 23, 1939, that the true gravity of the international crisis burst upon them. Speidel and the others left the conference in “undisguised consternation.”

8

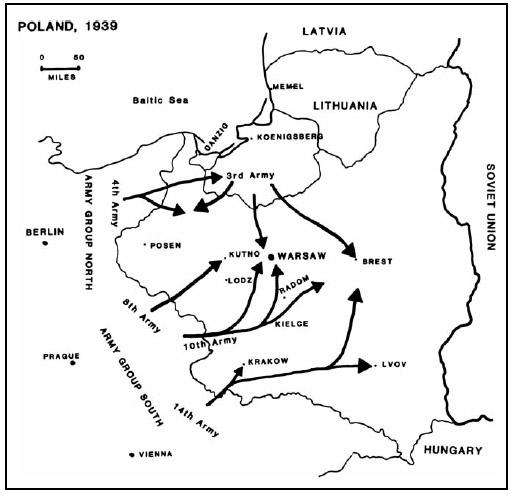

The German plan was as follows: the Third Army would attack westward from East Prussia and link up with the Fourth Army, advancing eastward from Pomerania, cutting the Polish Corridor. Meanwhile, to the south, Army Group South would advance on Warsaw, spearheaded by the Tenth Army. One and a half million German soldiers were committed to action against Poland. In the West, Col. Gen. Ritter Wilhelm von Leeb’s Army Group C would cover the German rear from a possible attack by the French and British. Table

3

shows the German Army Order of Battle in August 1939, and Map

3

shows the Polish campaign and the initial dispositions of the major air and army units.

The Luftwaffe deployed rapidly behind the army. Kesselring’s 1st Air Fleet was given the mission of supporting Army Group North, while Loehr’s 4th Air Fleet supported Army Group South, the main thrust of the German invasion. To the west, Felmy’s 2nd Air Fleet covered Army Group C’s northern sector and was charged with the air defense of northwestern Germany. Sperrle’s 3d Air Fleet had the same responsibility for southwestern Germany.

First Air Fleet initially had the bulk of the German strength on August 31, 1939: 795 aircraft, of which 519 (or 65.3 percent) were bomb carriers. Its principal subordinate units were the 1st Air Division (Lt. Gen. Ulrich Grauert) and Air Command East Prussia (Gen. of Flyers Wilhelm Wimmer), which included Lt. Gen. Helmut Foerster’s Luftwaffe Training Division, the Lehrdivision. Foerster was charged with the task of supporting the Third Army in East Prussia, while the 1st Air Division supported the Fourth Army.

To the south, 4th Air Fleet had 507 aircraft, of which 360 (or 71 percent) were bomb carriers. Loehr’s air fleet included the 2nd Air Division (Lt. Gen. Bruno Loerzer) and

Fliegerfuehrer z.b.V.

, or Special Purposes Air Command, under Major General Baron von Richthofen. Loerzer was charged with supporting Army Group South, while Richthofen had a special mission: supporting the panzer-heavy Tenth Army, the spearhead of the German advance.

Map 3: Poland, 1939

Map 3: Poland, 1939