Eagles of the Third Reich: Men of the Luftwaffe in WWII (Stackpole Military History Series) (8 page)

Authors: Samuel W. Mitcham

As if the lack of clear leadership were not enough, the Luftwaffe’s production program got completely out of hand after the Sudetenland crisis of September, 1938. Hitler brought Europe to the brink of war that month, before the Allies backed down at the last moment, signed the Munich accords, and abandoned Czechoslovakia to the mercies of Nazi Germany. However, during this crisis, Hitler, for the first time, saw that he might eventually have to fight Great Britain, whether he wanted to or not. He asked Goering what the Luftwaffe’s chances were of winning an air war against England. Goering turned the problem over to General Felmy, the commander of Luftwaffe Group 2 (later 2nd Air Fleet).

Hellmuth Felmy, who was born in Berlin on May 28, 1885, was a veteran of thirty-four years’ service. He joined the Imperial Army as a

Fahnenjunker

in the 61st Infantry Regiment in 1904. Commissioned second lieutenant in 1905, he went to flight school in 1912 and underwent General Staff training at the War Academy in Berlin the following year. During World War I he commanded air squadrons at the front and was engaged in setting up colonial air units. During the Reichswehr era (1919–32) he alternated between infantry and aviation assignments and was deeply involved in the secret air force. He was commander of the 17th Infantry Regiment when he transferred to the Luftwaffe in 1933. In the air force he had been commander of the aviation schools in the Berlin area (1933–35), the senior air commander, Munich (1935–36), and commander of Luftkreis VII (1936–38). After slow promotions in his early career (typical of a small army), he advanced rapidly in the 1930s. He was promoted to first lieutenant (1913), captain (1914), major (1931), lieutenant colonel (1933), colonel (1936), major general (1937), lieutenant general (February 1, 1938), and general of flyers three days later.

32

Regarded as a solid General Staff and commanding officer, Felmy could be counted on to give Goering the correct answer—not necessarily the one he wanted to hear.

Felmy set up a special staff under his personal direction and thoroughly analyzed the problem. His investigations ended with a three-day “war game,” which resembled a modern-day CPX (command post exercise). After completing his staff study, Felmy reported back to Goering on September 22. His long memorandum concluded that “with our present available resources . . . a war of annihilation against England appears to be out of the question.”

33

Three weeks later, on October 14, 1938, Hitler ordered a major armaments program to deal with the possibility of a two-front war. The Luftwaffe was given priority under this program and was ordered to expand 500 percent.

The Luftwaffe General Staff studied the program and estimated that, in practice, this meant the production of 45,700 airplanes by the spring of 1942. The program (later dubbed the “Hitler Program”) would cost an estimated sixty billion reichsmarks—about equal to the total amount spent on rearmament by all of the military branches between 1933 and 1939. Clearly it was impossible. Udet was among those who opposed it, stating that the mere fueling of the more than one hundred aircraft wings the program would create would require Germany to import about 85 percent of the world’s current output of aviation fuel. Joseph Kammhuber, the chief of the Organizations Branch of RLM, came up with an alternative plan, which cut the Fuehrer’s requirements by two-thirds.

34

Lieutenant Colonel Kammhuber was one of the brightest young General Staff officers Defense Minister Werner von Blomberg had transferred to the Luftwaffe in 1933. A native of Burgkirchen, Upper Bavaria, he had entered the service as a private upon the outbreak of World War I and spent four years in Bavarian infantry units. Promoted to second lieutenant in 1917, he was selected for the Reichsheer, trained for the secret General Staff in Stettin and Berlin between 1926 and 1929, and did his pilot’s training at the secret German air base in Russia in 1930. He served on the operations staff of the clandestine General Staff until 1933, when he joined the Organizations Department of RLM. After a year’s troop duty as commander of a night fighter group, he had returned to the Air Ministry as chief of the Organizations Branch in 1937. After the war he became the commander of the West German Air Force.

35

Summoned by State Secretary Milch on November 28, the RLM heads met, without Goering. One by one they declared even the Kammhuber Program unworkable. Stumpff, then still chief of the General Staff, suggested that it be adopted as an interim target. Milch suggested that he and Kammhuber go to Goering and put the idea to him. Colonel Jeschonnek, then chief of operations of the General Staff, objected to this. “In my view it is not our duty to betray the Fuehrer’s ideas like this!” he snapped. For some reason, Milch then replied: “All right, Jeschonnek, you come along with me to the Field Marshal!” This was a terrible mistake on Milch’s part. Goering, as always anxious not to disagree with Hitler, sided with Jeschonnek. Milch returned to RLM and announced that, even if Hitler’s program could not be carried out, every department chief would have to do his utmost to see that as much of it as possible was achieved. Kammhuber demanded to know where the resources were to come from. He received no answer. “Thereafter,” he remarked later, “the Luftwaffe drifted.”

36

Seeing disaster on the horizon, a disgusted and angry Joseph Kammhuber applied for transfer and was sent to Braunschweig as chief of staff of the 2nd Air Fleet. It was left to the incompetent Udet to try to carry out a program which even he knew was impossible.

CHAPTER 3

Spain: The First Battle

T

he Luftwaffe’s first campaign dates from July 17, 1936—just three weeks after the death of General Wever. On that date Jose Sanjurjo, Francisco Franco, and other dissatisfied Spanish generals launched a coup against the Spanish government in Madrid. The success of the coup was mixed. The Army of Africa in Spanish Morocco went over to Franco, and soon the Nationalists had overrun the entire colony. However, the attempted takeover failed in Madrid, Barcelona, and most of the coastal cities, where the rebel forces were massacred. Then Gen. Jose Sanjurjo was killed in a plane crash, leaving Franco in charge of the entire rebellion.

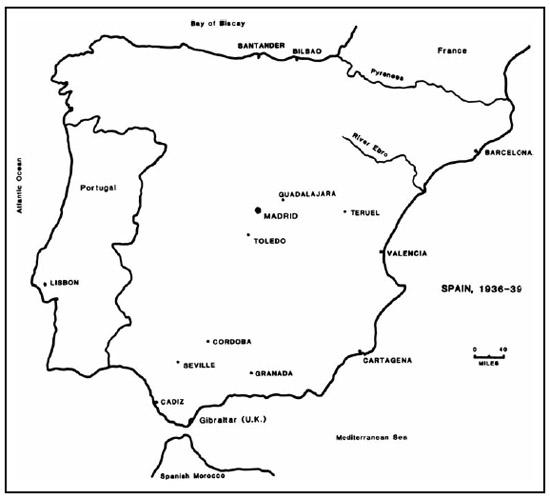

General Franco, then forty-four, was the extremely tough former commander of the Spanish foreign legion. Once he had personally shot and killed a legionnaire for mocking his high-pitched voice. Franco now faced a serious problem. He had planned on ferrying his troops across the Strait of Gibraltar via Spanish naval ships, but the sailors remained loyal to the Republic. They rebelled, killed their officers, and left Franco isolated in Morocco. The Spanish air force also remained loyal to Madrid. Although they held a large part of northern Spain, the rebel footholds in southern Spain were soon reduced to enclaves around Seville, Granada, and Cadiz

1

(see Map

2

). Unless Franco could get his main combat troops to the mainland, the surviving rebel forces would soon be wiped out and the rebellion doomed. The pro-Fascist Franco had no choice but to seek outside aid. He sent delegations to Rome and Berlin, to appeal to Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler for help.

2

Hitler received Franco’s delegation on July 25 at Bayreuth, where he was attending the Wagner festival. Goering, Milch, and Adm. Wilhelm Canaris, the chief of military intelligence, all favored intervention. Without bothering to consult the Foreign Ministry (then headed by Baron Konstantin von Neurath), Hitler promised to send aid. The next day twenty Ju-52 transports took off for Seville and Tetuan, Spanish Morocco. During the next month they conducted the first military airlift in history. Meanwhile, on the evening of July 25, Special Staff W (

Sonderstab W

) was set up in Berlin under Lt. Gen. Helmut Wilberg to supervise the German military aid mission to Spain, while Lt. Col. Walter Warlimont was soon dispatched to Franco’s headquarters to take charge of all German military and economic involvement in Spain. By the end of the month six He-51 fighters and twenty 20mm antiaircraft guns had been dispatched by sea from Hamburg.

3

As summer turned into fall, German military involvement escalated. In August, army major Ritter Wilhelm von Thoma, who later commanded the Afrika Korps at El Alamein, arrived in Spain to train Nationalist troops. Later that year he assumed command of the German panzer forces in Spain, which eventually totalled four tank companies. These, however, were never part of the Condor Legion.

4

Franco’s Nationalists were unable to win a quick victory over the Republicans (or Loyalists), and soon French and Soviet air units were flying in support of the government. The Soviet military aid was massive and included a large number of excellent tanks. The Fuehrer viewed the Russian involvement as a threat to the peace of Europe, so in late October he decided to activate the Condor Legion. It was set up to direct all German air and anti-aircraft forces in Spain. The units of the legion, which eventually totalled 4,500 men, assembled at Stettin and Swinemuende and sailed through the Baltic Sea and the English Channel to Seville. The pilots and air crews flew thirty-three aircraft from Germany to Rome to Sardinia and joined the ground crews, communications troops, and previously transported aviation forces in Spain. They suffered no losses en route.

The first commander of the Condor Legion was a big, ugly, heavy-jowled bear of a man named Hugo Sperrle. The son of a brewer, he was born in Ludwigsburg, Wuerttemburg, on February 2, 1885. He joined the 8th Wuerttemburg Infantry Regiment as a

Fahnenjunker

in 1903 and remained with his unit for years. He became a second lieutenant about a year after joining the 8th, was promoted to first lieutenant in 1913, and became a captain in late 1914. He was training as an artillery spotter when World War I broke out.

Sperrle did not distinguish himself in the Great War to the degree that Goering, Udet, and Loerzer did, but he still compiled a solid record in that conflict, where he specialized in aerial reconnaissance. He first served as an aerial observer with the 4th Field Flying Detachment (

Feldfliegerabteilung

). Later he underwent pilots’ training and led the 42d and 60th Field Flying Detachments and the 13th Field Flying Group, before assuming command of the Air Observers’ School at Cologne. When the war ended he was officer-in-charge of all flying units attached to the seventh Army on the western front. After the kaiser fell, Sperrle promptly joined the Luettwitz Freikorps and commanded its aviation detachment. In 1919 he was named one of the 180 former aviators in the 4,000-man officer corps of the Reichsheer.

Back in the infantry, Captain Sperrle served on the staff of Wehrkreis V (Military District V) at Stuttgart (1919–23), in the Defense Ministry (1923–24), and with the 4th Infantry Division at Dresden (1924–25). He maintained his interest in aviation and underwent secret advanced flight training at the clandestine German base at Lipetz, Russia, in 1928. He also made at least two trips to England to observe Royal Air Force displays.

Map 2: Spain, 1936–39

Map 2: Spain, 1936–39