Eating Aliens: One Man's Adventures Hunting Invasive Animal Species (24 page)

Read Eating Aliens: One Man's Adventures Hunting Invasive Animal Species Online

Authors: Jackson Landers

Videos of snakeheads in aquariums confirm that these fish pay a lot of attention to what’s happening above them. You’ll usually see them looking at the spot where food is dropped down to them seconds later, as if they’ve seen signs of an imminent meal. In the wild, they react to movement above them too quickly to be taken with a cast net. (And I know; I’ve tried.) Apparently this reflex helps them feed on terrestrial prey.

I looked at the slowing ripples on the water and considered my Scum Frog. What I probably needed was a Scum Goldfinch.

Soon after the goldfinch incident, I cast my Scum Frog into a sweet spot where I was convinced there’d be a snakehead. A hit resulted immediately upon impact. I fought the moderate-sized fish and got a good look at it when it broke water. And then suddenly it was off and gone. I reeled in the Scum Frog and examined it. The legs were shredded but still attached.

I realized why I wasn’t landing any snakeheads with the Scum Frog. The fish weren’t swallowing it, as would a bass. They were biting the back legs and trying to tear them off to eat; they weren’t getting hooked. I was only dragging them in for as long as they cared to clamp onto the rubber frog legs. The fish could let go whenever it wanted to.

By six o’clock, my whole body ached. I hadn’t sat down or eaten in eleven hours. I figured I’d cast that fishing rod about a thousand times over the course of the day. Perhaps it was a blessing that by six thirty, I’d finally lost good old Scum Frog to that dangerous snag of a tree in the middle of the pond. Without the only lure that had worked at all, I was done for the day.

I came back early the next morning with an array of similar frog lures. Again I pounded the pond for hours on end, and again I had many strikes but hooked not a one. Running low on money for campgrounds and motels, I drove home to figure out how to land this challenging fish.

Unfortunately, as of this writing, I haven’t managed to land a snakehead. I went back again and again all through the late summer and fall, camping up the road and spending my days casting for snakeheads until my wrists felt as if they would fall off. I saw plenty of them, and out of all the invasive species I hunted, I learned more about snakeheads through observation than I did about anything else, but they eluded me to the end.

From Aoudad to Zebra in the Texas Hill Country

I knew I’d spent too much time in the Hill Country of central Texas when we drove past a pair of dusty zebras standing by the side of the road and I didn’t slow down to take a picture.

Willie Nelson’s voice blared from the radio, and the car itself hummed beneath me as I downshifted around a corner, up a hill, past thickets of dying oaks and high fences and white limestone cliffs. It was the same car that had carried me thousands of miles around the country while I worked on this book — a little Ford ZX2 coupe, which I had usually piloted alone, with only the radio to talk to.

This time I had company. Helenah Swedberg, a documentary filmmaker, rode shotgun, keeping me awake and helping with directions. She’d found me through the Internet a few months earlier and started filming shortly thereafter. Many people have asked me to film documentaries or television pilots with them. Helenah, though, was unique: She’d gotten right on a train when I suggested we get to work rather than go back and forth with budgets and outlines and waiting for someone else’s blessing for the project.

My trunk was packed with the usual guns, butchering tools, nets, fishing tackle, and camping gear. The backseat was heaped with Helenah’s camera and sound equipment. I’m pretty good with a map, but I liked hearing the directions in a soft Swedish accent coming from a pretty blonde in the passenger seat.

I’d heard stories about hunting in Texas, particularly in the Hill Country. They were stories about enormous game ranches with almost every kind of animal you could imagine: African antelopes, such as kudu, impala, and sable. Strange Asian deer. Even rhinos, elephants, and lions. These are breeding populations of any animal to which a monetary or status value could be attached. If these animals were out there behind high fences for long enough, I thought, sooner or later a fence would get knocked down or a gate left open and animals would escape. For someone hunting invasive species, Texas could be Hell or the Promised Land, depending on how you look at it.

When I was offered a November residency for artists and writers on a large ranch between the towns of Kerr and Medina, I jumped on it. And when Helenah started following me everywhere with a camera, I suggested that she apply for the same residency in order to film on the ranch and to facilitate an epic road trip. Having someone to pay for half the gas was a nice angle, too.

We left Virginia as the leaves were changing, drove through the Deep South and the barbecue belt and along the Gulf Coast. The fall colors faded to green as we seemed to go backward in time. Somewhere in Mississippi the palm trees appeared and the barbecue joints became catfish houses and shacks with signs advertising boiled crawfish. Soon, we were in the Texas Hill Country, a part of the state suffering from what was shaping up to be a prolonged drought of historical proportions. Later in the trip, near San Antonio, I saw horses and cattle lying newly dead in their pastures, grim and emaciated. Fortunately, our host ranch possessed several natural springs and had more access to water than any other place I visited in the region.

The owners of the ranch had awarded me the residency based in large part on the work I was doing: creating awareness about invasive species. They’d been quoted in a newspaper article decrying the ecological and economic effects of the 2.6 million invasive pigs that plague Texas. Having hunted wild pigs, I was more interested in the other invasive species found in the Hill Country, such as aoudad, axis deer, and emu.

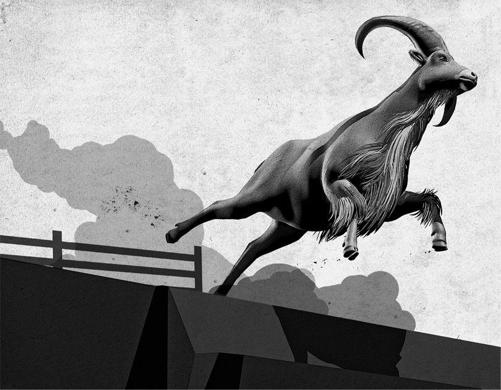

The Hill Country is, in a sense, one big private zoo. In the 1950s, a sort of fad developed when a rancher bought some excess aoudad from a public zoo and released them on his large, fenced property. Aoudad, also known as Barbary sheep, are native to the deserts of northern Africa and somewhat resemble bighorn sheep. They can survive without liquid water, getting all of their moisture from the plants that they eat: a ready-made survivor in dry country.

The aoudads reproduced quickly and were sold to neighboring ranchers as exotic pets and as big game for eventual hunting. Other species followed. In an area of families flush with oil money and sitting on enormous tracts of land, keeping the strangest game animals they could find was the new status symbol.

A few ranchers realized there might be some money in this. If people were willing to fly to Africa to hunt antelope, perhaps offering the same antelope to hunt closer to home would have appeal. The business of raising trophy-quality exotic game emerged. Raised either wholly wild or half-tame on big ranches, these animals became a cottage industry. Anything that a hunter would pay to go after was imported for this “sport.”

Most landowners built high fences around their property; after all, nobody wanted to pay to stock impala if they were going to wander over to somebody else’s land. Had the animals stayed put, maybe this scheme would have worked out. If there’s one lesson to learn about invasive species, however, it’s that wildlife doesn’t want to stay put.

Our first morning in Texas, Helenah and I were looking for the ranch manager’s house when we saw an axis deer — a species of spotted deer native to India — with a collar around its neck, standing in front of a tidy, one-story house. No fence confined it; in fact, it walked over and sniffed my hand like it was a dog. (I was told later that the deer had been found as a fawn and bottle-raised by the ranch manager’s children. Eventually, it mated with a passing wild axis buck and had fawns of its own.)

At first I was delighted by the opportunity to see and even touch an axis deer. But soon I realized that the fact these exotic deer were being kept as pets didn’t bode well for my chances of hunting them.

Helenah and I caught up with Robert, the ranch manager, a cheerful, portly, mustachioed man in his fifties sporting an air of competence. When I asked him about aoudads and pigs, he told me the ranch owners had decided against my hunting for a while. A group of people who had paid to hunt on the property would arrive in a few days, and my hosts didn’t want my shooting to spook the deer and pigs these people would be looking for.

This was a disappointment, but I understood the situation. I believed the owners’ commitment to sound ecological practices: No high fences enclosed the property (allowing wildlife to freely cross boundaries, which has become the exception in much of Texas), and the fact that they raised bison rather than conventional cattle spoke to their willingness to encourage native species.

Because I didn’t want to waste any time, I begged my hosts for one exception: that I be permitted to hunt invasive species on the ranch right away, but without the use of firearms. I would be on foot, armed only with a knife. They readily agreed.

Over the next few days, Helenah and I hiked and drove around the enormous ranch, gathering fossils, dodging bison, and filming material for her documentary. Herds of six to twenty wild pigs would emerge from thick cover and feed during the half hour before dusk. Whitetail deer were more plentiful on the ranch than anywhere else I’ve ever been. Now and then, I’d spot an Indian axis deer or a European fallow deer, easily distinguished from the native deer by the spotted coats of the adults.

My method of hunting began with me running after every group of pigs we saw. Usually at night, we’d be driving down one of the many dirt roads and spot the shapes of pigs in front of us or in a field. Helenah never got accustomed to my habit of suddenly stopping the car, jumping out, and running after a herd of pigs in the moonlight. Perhaps I could have been more diligent about setting the emergency brake before leaving her in the idling vehicle.

Sometimes I stalked them on foot before running for the final approach. Over the course of a week, I discovered several tricks to getting in close. A herd of fewer pigs was easier to stalk toward; there were fewer eyes to see me. The more ground I could cover by stalking rather than running, the better. Once I started sprinting at the pigs, they’d hear me, and when they began to run, it would all be over in less than thirty seconds. I needed to get to within twenty five yards (and preferably closer) or it was impossible to catch up with them before they’d make it into the woods. I could pursue them only in the open, as I’d lose sight of them in any sort of cover.

The use of slopes also proved key. If the pigs were even slightly uphill from me, I couldn’t gain an inch of ground. On flat land, we were evenly matched. The ideal was to be running slightly (but not steeply) downhill at my prey.

I knew better than to try for a big one. Some of the pigs were well over three hundred pounds, and I stayed away from them. Without a pistol for backup, a boar or sow of that size could gore and bite me and possibly even kill me. I also wasn’t going to touch any piglets, lest a large sow run over to defend her baby. My target, then, was a smallish pig between fifty and a hundred pounds, preferably toward the rear of the pack and without a really big pig next to it.

One night, shortly after dinner, Helenah looked out through the kitchen window and informed me that a herd of pigs was on the lawn. I sprang into action and ran out the door into the grunting, oinking herd.

My feet pounded the ground, and the sensation of a thorn poking into the sole of one foot brought home the fact that I had forgotten to put on shoes. Barefoot running is fine for some people, but a ranch dotted with piles of bison poop and thorny shrubs, in the dark, isn’t the place for this kind of activity.

Nevertheless, I pressed on, encouraged that I was closer to getting a pig than ever before. I was only a few yards from a small one and could sense imminent victory. A few paces, and I could pounce on it and slip the long blade of my knife into the middle of the right shoulder, where lies the heart. My right hand went to my hip for the familiar feel of the hilt in its sheath and felt . . . nothing.

In the excitement of the moment, I had dashed from the cottage lacking not only my shoes but also my knife. It was still sitting on the kitchen counter, where I’d used it to chop vegetables.

I quickly had to acknowledge that there were a few boar in the herd big enough to do damage. As things stood, though, with me flying through the air in the moonlight, these animals were terrified of me. They had no idea that I couldn’t defend myself against the tusks of even a medium-sized pig. To stop and turn around could be interpreted as a sign of weakness. I thought the best thing to do was to bluff and keep on chasing. I ran after them most of the way across the pasture through the short, stiff grass and the jimsonweed until they were well ahead of me. I was safe.