Edie (24 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

Bobby and the girl had a kind of closeness. The language of looks. Somebody would say something preposterous, and you could see there was a great deal of intimacy between them. She had a faint Mexican accent. She hardly ever spoke . . . a kind of silent Dolores del Rio type. She was working as a secretary, but she had that kind of poise that South American women have when they come from good families. She had long black hair—very full and beautiful—and enormous brown eyes; a quizzical smile. She was kind of madonnalike, but she could be very funny. With her it seemed that his life had opened up. But there was stuff that worried me. He had been doing some strong-arm stuff in a labor organization and told me when he returned that nobody was going to push him around. I remember one night a kid came into my house and made a bit of a pest of himself. Something snapped inside Bobby’s head and he took the kid and threw him down my front stoop. He just put him up over his head and threw him down. The kid was a little snotty, but you don’t throw kids down the stairs.

JOHN ANTHONY WALKER

When Edie used to visit Cambridge, she’d bring Bobby to the Casablanca bar. “Meet my brother.” She really loved him. I remember this huge motorcycle jacket on him . . . the size of him . . . the big boots . . . the initial impression visually at a distance was of a Hell’s Angel coming through the door. Of course, Bobby wasn’t that at all. He would sit in the Casa B with this sweet, gentle smile that you’d only find really on an imbecile, except he wasn’t an imbecile. There was something just incredibly sweet, childishly sweet about him, like Prince Myshkin in

The Idiot.

He was a Santa Claus from the skies wearing a motorcycle jacket. A sense of warmth and love and protection. Edie was a little girl looking up at him.

SUKY SEDGWICK

Cambridge was too suffocating for Edie. She had some opportunities in New York—that’s the way I understood it. Bright lights! Hit the big town there and kick up your heels and have fun! She wanted to kick out and do some things. She wanted to be in a bigger space, and New York offered a bigger space for her. Everybody knew Edie. That was even mortifying for me. “You’re Edie’s sister? You’re

Edie’s

sister?” Edie’s sister . . . Edie this, Edie that, Edie everywhere. She was famous. Cambridge was too small for her.

GORDON BALDWIN

Edie was not

that

involved in her horse sculpture; she kept covering it with damp towels and there was a question of whether or not it would dry out irreparably. She felt that the Casa B and Cambridge were “not enough.” New York had a real night life. It was a natural migration.

I helped her pack and drove her to New York in her Mercedes-Benz. The car was completely filled with mismatched luggage, boxes, parcels, and such miscellaneous objects as stuffed animals, straw baskets, and a large collection of unpacked hats. On one of the turnpikes Edie pulled into a Howard Johnson’s under the impression that it was a long row of phone booths. Her visibility may have been bad with all that luggage, but that was typical of Edie’s kind of vagueness.

I think her idea was to model in New York. Much of that summer of 1964 she went to a salon where they literally pounded her legs into shape. Her legs were not good in those days—piano legs—but by the time the course was over she ended up with those legs that were so famously beautiful.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

Edie was living at our grandmother’s apartment at Seventy-first and Park. She saw uptown people. But she felt awkward being at our grandmother’s and her bizarre habits were a great strain on the household—the servants were going bananas. Edie would take off on these enormous spending sprees: her closets and drawers were crammed full. I’ve never seen so many clothes in my life I Never I Never! Just incredible. Edie used the place rather the way we all did . . . staying there the way you stay at a club . . . but it got out of hand.

The apartment was well decorated but not especially pleasant. It was horribly dark because our grandmother refused to live any higher in an apartment building than she could walk down. She had a fear of elevators. She wanted to be within walking distance of an Episcopalian church. So the apartment was on the fourth floor, and the electric lights had to be on twenty-four hours a day. Heavily curtained. The furniture was English and very elegant. Naval battle scenes on the dining-room walls. Pale English vistas. Our grandmother lived at the end of a long corridor. People seldom went to see her after she became senile.

SHARON PREMOLI

She kept to her bed most of the time. Edie told me she read the newspapers upside down. She asked me once what she should give her grandmother for her birthday. I suggested candy, or perhaps she could take her to the movies. A few days later I asked Edie what she had done about the birthday. She said, “I found the most wonderful thing for her. I went into Bendel’s and found this beautiful gold evening purse.”

I burst out laughing and asked if her grandmother had known what it was. Edie said, “She loved it!”

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

Edie had always dressed to conform to my mother’s taste—little Peck and Peck costumes with navy blue sweaters—but in New York one day I suddenly saw her in this little red fox fur waistcoat with a matching hat and huge peacock-feather earrings, some kind of outlandish bag, black stockings, and high-heeled boots, none of which was in fashion then at all. I was very shocked. I said to her, “Is that the way you want to go around?” She said, “I think if s fun.”

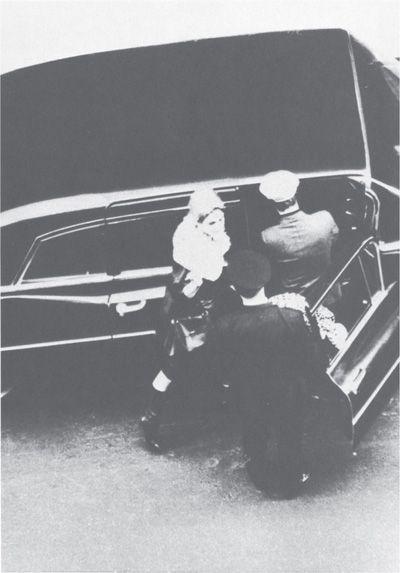

Edie and her limousine

JOHN ANTHONY WALKER

Because she had this whole thing about modeling, she tried out for Miss Teenager in one of those teenage magazines. They accepted her with great happiness. Then they found out she was no longer a teenager. It was typical of the helter-skelter life she was leading when she first came to New York that summer.

I remember asking her up for the weekend to Fishers Island. What happened was typical, too. First she telephoned from New London to say that she’d missed the ferry boat to the island. New London’s a strange town to be caught in if you’ve missed the ferry. A railroad town; a harbor stop. In the old days what I would have done was spend the night at the Mohican Hotel and catch the ferry the next day. The Mohican was big and old and very nice, but it was not the sort of hotel Edie would be caught spending a night in. So I told her, “Rest easy. Go to the airport at Groton and they’ll fly you across. Well pick you up; it’s a ten-minute flight.”

So I went down to the little Fishers Island airstrip to meet her. It had been sort of a drizzling day and the fog began to roll in. The foghorn you hear on Fishers Island is the same one that Eugene O’NeI’ll heard when he was writing

Long Day’s Journey into Night

in New London. O’Neill’s foghorn was blowing wildly; you couldn’t see the lighthouse. The man in the airstrip office said, “They’ll never take off from New London.” We were totally shrouded. Just as he said that, there was this purr of the motor up in the air. So the guy said, “Well, hell never land; hell never find us.” But suddenly we heard the sound of the airplane coming in to land, the increasing roar as it came down closer. Then the yellow undercarriage appeared out of the fog, not more than five or ten feet above the runway. We all went, “Wow!” I could have run out and caught the

wheels

as they went by. Then the undercarriage disappeared up into the fogbank and the sound of the airplane disappeared. I could sense Edie trying to get down at all costs until the pilot told her, “Lady, I don’t care who you are, I’m

not

going to land here I”

I went back to the house and wondered what to do. How was I to find Edie in New London? How could I get through to her? All this turmoil . . . with Edie I always felt a considerable responsibility. I think I even tried to call the local lobsterman to see if he could go over

to the mainland and pick her up. In the middle of all this there was a phone call—a ship-to-shore relay. It occurred to me that my only contact with Edie that whole day had been sound: the purr of the airplane, and now this disembodied voice from the high seas. Edie said, “The captain says in another half hour well be getting in.” I could hear the clink of glasses in the background and somebody saying, “West Harbor, West Harbor.”

So we went down to the West Harbor dock and in she came, sailing happily out of the fog, on Jock Whitney’s yacht. Edie had arranged it somehow. It was a fine entrance. She was totally the center of attraction. I remember exactly how the yacht arrived out of the fog—first of all the bow and all these men in white running up and down with ropes, and then the bridge with the captain, the radar going dot, dot, dot, dot, and the lighted portholes, and then the brass, polished teak, highly formal living room pulled in with Edie in the middle of it surrounded by people in director’s chairs.

So we got her on the island. That night we went to the Buckner coming-out party. Mrs. Buckner is the daughter of Thomas Watson, the founder of IBM, the man who said,

THINK.

I had grown up with the sons, Walker and Thomas. The young children of these families, the scions, raced in these little boats about eight, ten feet long. It was good high-key times. But the fathers on the docks took it very seriously. It

was

IBM versus the National Gallery, or whatever. The nannies came down to watch the races. It really was important to these people watching us in our first competitive acts, and it was always strange coming in from these wet, flappy races, which were rather fun, into this tension. For instance, Walker Buckner once lost a race because he hadn’t bailed out his boat. He was made to walk around their place carrying two metal galvanized buckets filled with water so he’d become more aware of how heavy water was—quite a heavy trip to lay on a little kid ! After a few years of bailing out the boat, he said, “Fuck it all,” and went off to play jazz in California.

Well, that night the Buckners had a dance for their two daughters at Barley Field Cove—Mary Gentry and Elizabeth. It was informally understood that we could go. It wasn’t something I had intended to do, but Edie loved parties. She

adored

parties.

I remember they had trucked in a lighted fountain. Perhaps it came from Hammacher Schlemmer. They must have brought it over on the ferry. There was a huge tent, but it was fancier really . . . perhaps a pavilion. You could see out of it to the lawn which rolled down to the water. It was an impeccable lawn. A lot of my life has been involved

with the lawns of Fishers Island. This one was a turf lawn, truckloads and truckloads of sod brought over from New London and put down from the house to the ocean. It was very well kept up. It rolled down to the ocean, there was a bit of hard scrabble, then a drop and the beach below it. It was a very comfortable party. Many of the young had been flown in—the graduating class of Groton or whatever. There was a band. Lester Lanin. People dancing. A young man on Fishers Island then wore a white jacket, a ruffly-tuffly shirt, and a somber black tie. Possibly, if you were making a statement of fashion, you might wear plaid trousers neatly pressed.

I believe Edie was wearing leotards; whatever, it must have been a little exotic, because I remember being rather proud to be sitting at that table with her under the marquee; she had become the focus of a certain amount of attention.

The moon rose out of the ocean, spiraling up in the dark. It was the final touch—a nice moon rippling the ocean and turning everything silver. The combination of all this—champagne, the music, an idyllic setting with the ocean below—enchanted the party. Edie was very sensitive to enchantments. Also she was exuberant that weekend; she had so much energy and things were going well. She had been dancing inside earlier that evening, getting more and more extravagant, especially in the foxtrot, and now, outside the marquee on that moonlit lawn, she broke away from the form completely and was doing these totally free dance movements. We looked out from under the marquee and there she was on this deserted lawn—a brilliant green during the day and which had taken on its own tonalities of color under the moon—and she was cartwheeling across it . . .

cartwheeling.

She was an exquisite dancer and dancing purely for herself, a part of the tenuous enchantment of the evening. I remember the music dying down as the focus of attention shifted to her out there, and I suppose that since she couldn’t see into the light, she was totally unaware of us.

The next day we were having a Fishers Island picnic at Isabella Beach—one of those picnics where the consomme and vodka come in thermoses and you toast the idyllic summer days with plastic cups. Edie had disappeared. It was a bit spooky. Somebody said, “We saw her go swimming.” But she was nowhere in sight on this beach. Then somebody else said, “Is that her? Way, way out?”