Edie (26 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

“Oh, her parents are so nutty,” they’d say, “they won’t even notice. They’ll just pay and pay.”

So after a while I figured, “Why not?” I didn’t feel guilty or as if I was sponging. I felt like we were just redistributing the wealth.

TOM GOODWIN

All the time the money was flowing out. Edie went through eighty thousand dollars in six months—the delicatessen, L’Avventura, the Bermuda Limousine Service. There were various mysterious men who handled her money. I remember going downtown with her one day in the limousine. She was told she didn’t have any more money. She refused to let that be a possibility. Her mother and father had all this money, and she should have it, too. She came out angry, indignant.

She would take her friends to her grandmother’s apartment. Amazing place. Her grandmother was a vegetable. Edie would make fun of it all and serve us drinks. Edie aced:

the

young princess needs her food and drinks. And yet at the same time she had a tremendous compassion for crazy people; she talked about them, those “who had seen the big sadness.” I remember a long conversation we had about

the big sadness . . . the whole thing, you see, which she really saw larger than her own doom. It wasn’t feeling sorry for herself, this big sadness, but for suffering outside of herself. And yet she was amoral, a facile liar. She would steal, rob, rip off; she would get herself in awkward situations and lay something on somebody. She could push everybody to the farthest extent of indulgence. Methodically. She could bitch and moan and be prissy and infantile, demanding this and that . . . extra lemons! I remember squeezing endless lemons. She was scared to go to sleep. It was very hard for her to. I saw her desperate and unhappy like a caged animal. Yet she always had such energy . . . I mean, she’d run people ragged. “Let’s go. Let’s get into the limo!” She never wanted to cool out. She was always, like, pushing everything to the limit.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My father heard about all those shenanigans. He insisted that Edie come out to California for that Christmas of 1964 with the family. But Bobby, who was doing graduate work at Harvard, was not allowed to come home. What Bobby wanted was to be with Edie. He wanted to come down from Cambridge on his big motorcycle and they’d spend Christmas together, just the two of them, and she would show him New York. Edie and Bobby were very much alike. He kept speaking to me about having fallen in love with her. I think Bobby recognized himself in Edie, as if she were living out something for him. Bobby identified with her because she was young and beautiful, succeeding at that time against all odds, and he admired her, too, because she’d apparently found the weapon which absolutely neutralized the magic or power of our parents. What he especially loved about Edie was her outlandishness and her absolute abandon. He respected her for the mobility that she had socially. I don’t mean socially, capital S, or

Social Register.

I mean literally that she could move anywhere . . . like a creature moving in and out of those funny-shaped stones in a goldfish bowl.

Bobby told me the reason my parents gave for not wanting him to come home [for Christmas] was that he upset Jonathan. The message was: “Don’t disturb the other children. You’re a bad influence.” Edie had to go. So they all deserted Bobby. He must have felt that. He had really stacked it against himself: he had spent all his money and put himself in every way in an untenable position.

Bobby, July, 1964

SYDNEY J. FREEDBERG

The problem was that he was stI’ll self-destructive. There was an element of the suicidal in the way he used vehicles. He had smashed up his sports car earlier. I saw his motorcycle, like a Harley-Davidson monster, one of the big ones. I encountered him as I was going out the gates onto Massachusetts Avenue opposite the Porcellian Club. There was Bobby and this iron horse. He showed it to me with enormous pride; I expressed my displeasure and concern. I told him it was going to kI’ll him. He shrugged it off. I told him I thought it was extremely dangerous and not the right thing for him to have in his hands.

PETER SOURIAN

I was just going out in New York to a New Year’s Eve party. It was about seven-thirty. The doorbell rang and Bob came upstairs. He said, “Hi, how about a drink?” I said, “I’m going out.” I didn’t realize he was in difficulty. He seemed very breezy and relaxed. I didn’t pick it up—the cue. I mean, on New Year’s Eve when you appear like that . . . I mean, you ought to be able to translate. I wish he had screamed, “Goddammit, what are you going to a party for? You sit here with me.” But he didn’t. He wasn’t the type of guy who was going to tell you. We went down the street together and that’s the last time I saw him. It was that night, New Year’s Eve, that he crashed.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

Put-your-head-m-the-mouth-of-the-lion-trip—he would try it. One of those times the mouth is going to close, and that’s what happened. He was riding the lights up Eighth Avenue, just catching them as they turned, and he went into the side of a bus without his helmet.

SUKY SEDGWICK

What an imp Bobby was. He had been riding his stupid motorcycle. I told him to be careful because I knew Bobby was a violent little character, always thrashing around. He said, “I’ve got too many mothers.”

I prayed he’d die if he couldn’t recover completely from that accident. Because I knew Bobby could not be a vegetable. He was incapable of that, and that would have taken away his Bobbyness. And that couldn’t be. So I prayed both ways. That’s a pretty awful prayer.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

Bobby never regained consciousness. My sister Kate went every day to the hospital. I went once, but I couldn’t bear it—his head was covered in bandages to the bridge of his nose, and he was hooked up to all kinds of machines. He had one big bare arm out of the covers, and when I took his hand, a stream of tears ran down from under the bandages. The doctor told Kate it was just that his nose was irritated by the tubes.

He died on January 12, 1965—he was thirty-one years old. I heard that the obituary in the

Santa Barbara News-Press

reported that my father said there would be a service for Bobby in the East, but there was no funeral. My parents never came East. My husband and I collected Bobby’s things from the hospital—his sheepskin coat, all torn and bloody—and we went with the funeral director to the city morgue to identify him. We stood in a side room looking at a dark wall. Suddenly a light flashed on—just for a second—and there was Bobby lying on this shelf behind a window, like a gisant—a tomb figure—so very long and perfect. I remember his color seemed extraordinarily vivid. I gasped, and the light went off.

Then he was cremated and my father asked me to have Bobby’s ashes sent to him, care of General Delivery, Santa Barbara, so that the local postmaster in the Valley wouldn’t have to handle them. I don’t know where my brothers are really buried. I don’t think they’re buried anywhere.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

My father told me he took Bobby’s and Mitny’s ashes up to what’s called Center Ridge, which is a high-peaked ridge that goes through the center of Rancho Laguna. He rode up there alone with a little square box. He scattered the ashes on both sides of the ridge . . . I’m sure the wind took them in all directions. It was the backbone of the ranch, that ridge, incredibly steep in places, and we used to gallop the horses down the trails and up the other side. My father must have remembered how much fun we all had on that roller-coaster ridge. He went up there on a tall, regal horse named Tiger. He would have been wearing the old classic Spanish regalia—the visalia saddle, the Tapaderos stirrups, and the fancy bridle with the decorative tassels hanging down. He must have been a formidable sight. Leather leggings. His wide bucking belt. A straw-textured Stetson that he always kept centered very carefully on his head, without the slightest tilt: he always had to be centered.

One day, not long before my father died, we were coming back along that same ridge and that’s when he told me what he had done.

G. J. BARKER-BENFIELD

Almost at precisely the same time Bobby ran into the bus on New Year’s Eve, Edie was in a bad accident out in California. Edie was driving. There was a flashing red light and she didn’t stop. A big saloon car drove right into us. The car went into a lamp stand on the next street. My head went through the windshield. The car was totaled. They had it on TV—“How did two people step out of this car alive?” I was cut around the right eye and had to have twenty-two stitches. Edie, it turned out, had broken a knee. But she got out and began removing several hundred dollars’ worth of stuff from the trunk of that car which she had bought that afternoon in Santa Barbara, throwing it out on the sidewalk just in case the car blew up. Edie was very scared that her father was going to use this accident as an excuse to put her back in the loony bin. We talked things over in the hospital room. She decided that we’d leave undetected. Her mother was in cahoots with her. She came and picked us up in a station wagon. Edie’s leg was in plaster. Mrs. Sedgwick drove us to the ranch, and then we took our stuff and I drove Edie directly to the Los Angeles airport, where we had a drink, and then she boarded the next plane for New York. I never saw her again.

GILLIAN WALKER

After Bobby died, Edie told me, “I knew he was going to die . . . he killed himself.” It was like a part of her, she told

me, was standing by and watching the curse play itself out in the family. Her response to it was to suppress the whole matter by going back to the frantic way of life she was beginning to find for herself in New York.

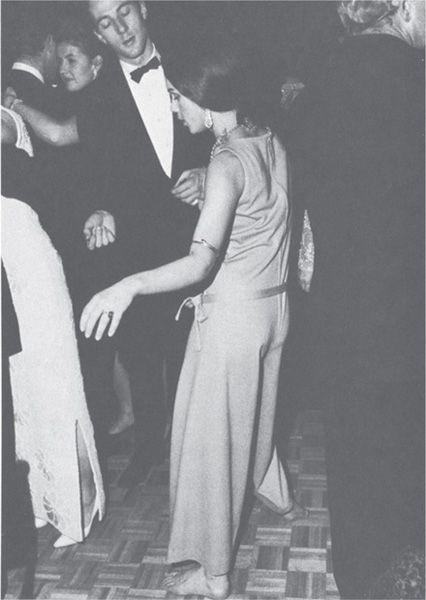

GEOFFREY GATES

Early in January there was a party at Ondine—a twist party—and through the morass of people I saw this rather pretty girl doing the most violent, deliberate kind of twist wearing a hip cast from toe to the hip. I recognized Edie. We lived in the same townhouse on Sixty-third Street. I couldn’t believe it. I went over to her table and asked, “What happened? Are you okay?” She said she’d crushed her knee in a car accident.

The smile was wild . . . manic. She kept getting up and dancing, one leg sheer white with only a couple of signatures on it just rooted to one spot on the floor, and the rest of her body spinning around the cast as if she were an acrobat.

She stI’ll had a girl’s finishing-school appearance, but her face and actions showed that something else was coming up very fast.

BOB NEDWIBIH

The doctors said she’d probably walk again, but with a limp. The fact that she had on a cast didn’t stop her. I remember her at Harlow’s, an uptown discotheque where the Young Rascals were playing in their Little Lord Fauntleroy suits. She had a sculptor come over and chisel off the cast. Then she sent a few of her escorts to the cloakroom for some coat hangers and tied them to her leg with neckties to make herself a splint. She proceeded to dance for the rest of the night. Her doctor was suggesting she’d be a permanent cripple and she was having none of it.

SANDY KIRKLAND

Edie was very frail and vulnerable. She was just psychologically scattered: she never finished a sentence, she never looked you in the face, she was never there. She wasn’t yet getting a lot of attention, so she was just kind of floating around. Very distracted. The only things she talked about were her father and her family and the Santa Barbara scene that she had just left. She had a deep worship of her father, and yet at the same time hating and resenting him because he had . . . well, she felt that he had fucked her around. I don’t know whether that was literal or not. If she got drunk, she would talk about him in a very physical way. Perhaps she felt violated by him because she worshiped him so much . . . almost a metaphor for something he was doing to her psychologically.