Edie (29 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

Andy Warhol, high school portrait

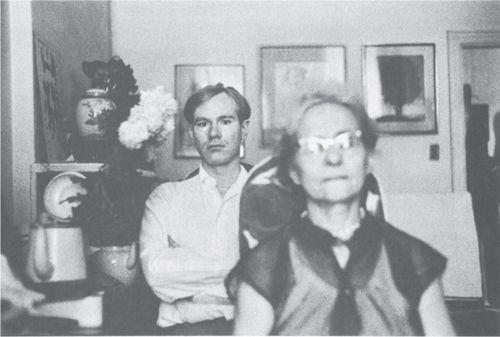

Andy and his mother in his apartment on Lexington Avenue

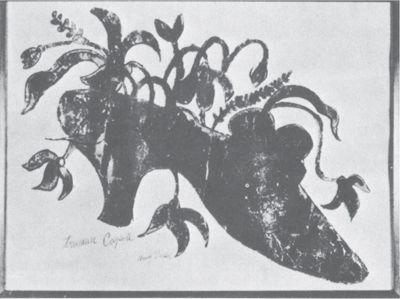

Andy’s gift to Truman Capote, 1954

WALTER HOPPS

. In early 1961 Irving Blum and I were staying in New York with David Herbert—we were all art dealers, but David was one of the more pioneering of us and had his ear to the ground as to what was really going on. He was mobile, let’s say, in the uptown New York gay world, as well as observant and mobile in the serious world of painting. Two different worlds. Sometimes the same. In the course of going about our business, looking into Jasper Johns and Bob Rauschenberg and rounding up some other stuff, David Herbert kept telling us, “Look, there’s someone you should see. His name is Andy Warhol.” It seemed like a funny name to me. He kept insisting that we should both go and visit this . . . this person.

Well, at the door was a peculiar, fey, strange-looking person. I sighed, thinking we were in for a cute time of it, and my reaction was reinforced as we went down hallways and I saw peculiar stashes of a kind of chi-chi gay taste . . . crannies full of gumball machines and merry-go-round horses and barber poles. I said, to myself, “Good Lord, this guy is a cute, rather effete decorator,” which was not especially novel since public taste was already on the edge of Tiffany glass. Everywhere in this townhouse, variations on this kind of taste were collected. We went into a foyer and looked down the hall at a great collection of material that seemed to reflect this . . . a stash of Forties wedgie shoes, which seemed kind of kinky. The townhouse, gloomy and large, was peculiarly unfurnished. It was more of a collecting depot, a warehouse of things. I said, “Gee, it looks like you collect a lot of gumball machines here.” He was some strange, isolated figure in his laboratory of taste experiments.

I started to look at some of the material. I was being a little nosy. Irving Blum was rolling his eyeballs at the ceiling, like, “Oh, my God, I didn’t want to lead you into

this;

this is not your cup of tea.” Actually I was fascinated.

Then Warhol led us into what seemed to be virtually a windowless room. It was a paneled library, but the bookshelves were empty . . . no pictures on the wall, nothing. Like it was being moved into or moved out of. What really made an impression was that the floor—I may exaggerate a little—was not a foot deep, but certainly covered wall to wall with every sort of pulp movie magazine, fan magazine, and trade sheet, having to do with popular stars from the movies or rock ‘n’ roll. Warhol wallowed in it. Pulp just littering the place edge to edge. As we walked in, the popular music of the time was blaring from a cheap hi-fi set-up; there was a mess of cushions, blankets, and maybe a little mattress. I don’t remember that there were any chairs.

I think we squatted, or maybe there was a little chair for one of us. But the extraordinary sight was all this pulp pop-star literature, and the thought of Warhol wallowing in it.

We didn’t know what to talk about. Neither Blum nor I knew who this person was or where to go with him. No art encountered us.

And we felt uncomfortable.

Warhol started to interview us! He wanted to know what we were doing in New York. “Well, we’re looking at paintings.” “Oh, what paintings?” Then it got to a particular focus. He asked, “Oh, what do you think of Jasper Johns?” I answered, “I think he’s a very serious man indeed.” Every remark I made was challenged: “Oh, you really think so? Why is that?” There was a kind of funny, bitchy edge to what he was asking. It was as though we had to pass a number of tests so that he could feel free to show us something.

Finally, one of us said, “Well now, do you have anything to show us at all?”

Up to that point Andy had been pushy and questioning . . . quite forward and talkative to a degree I have never heard since. “Well . . . uh!!! Yes,” he said, after a bit more dissembling.

He got up and walked over to the corner where there was a kind of closet door, and he literally had to get down and scrape away the magazines. He got the door open and came out first with a couple of smaller paintings. They were surprising enough. One was a stretched canvas or a piece of white linen, with a lot of bare space, which gave an unfinished effect—not the look of a Rauschenberg, but that’s what popped to mind. It was a Royal typewriter! Very carefully rendered, so that though there was some scumbling and other stuff around the edges, it looked just like an advertising illustration of an old-fashioned Royal typewriter. We looked at it in surprise. “Hmmm, that’s interesting,” we said, and the other things one says. But we

were

interested.

The second painting he brought out was a slightly different approach to paint application. Dick Tracy and his sidekick, Sam Ketchem, done in a sort of smeary, painterly way . . . a blow-up of these cartoon figures partly painted out but with loose paint on it.

All right! Finally he brought out the third thing, which looked like it was perhaps eight or ten feet tall, a rolled piece of linen . . . fine linen. He unrolled this thing out on the floor, over all that fan magazine junk. It was astounding! It was a larger-than-life-sized image of Superman flying, carrying Lois Lane, a blow-up painting in full color of a comic-book image. Flat, smooth application of the color. It didn’t

look anything like a painting. It wasn’t composed. It was just a big-sized scale of a comic-strip box! Well, that was already strange. We’d never seen anything like that at all. And there was something about the Superman image that did vary from the comic strip. In the strip, Superman himself and the characters are all kept in the same scale; he’s not larger-than-life. In this painting of Warhol’s, as I recall it, Superman is much bigger in scale than the Lois Lane he’s carrying in his arms: she’s not doll-sized, but miniaturized. We were just astounded. We looked at it a while, but even before we’d finished looking, Warhol rolled it up and put it away. That was that. We’d had a peek at the material, and now he’d cut the evening off. Odd. We’d arrived ready to get out of there as soon as we could, figuring this was going to be a bust-out, but now that we were intrigued, Warhol was concluding things. To get us out of that room he suggested that he had an interesting little book we might enjoy, that his mother—up to this time we’d never heard of Andy Warhol’s mother—had done. We were taken to another room, downstairs, I think. Like a creepy scene out of

Psycho.

Andy went off into some shadowy corridor, talking off there . . . I’ve often wondered if as in

Psycho

there really

was

a mother . . . and he finally came back with this strange, campy little privately printed book called

Holy Cats

done in this curious kind of gay illustrator’s technique . . . quite unlike the stuff we’d seen upstairs. By now we were totally confused. What did this have to do with anything? He gave us each a copy and then he said, “Oh, I must have my mother sign them for you!” He took them back and disappeared into another room again and got them signed. There was some fumbling around, a delay. To this day I don’t know whether his mother signed, or if he just went in there, fumbled around, and signed it himself. It was signed, “Andy Warhol’s Mother.”

I have never seen that Superman/Lois Lane painting since. He put things of that kind away. He had many more tricks up his sleeve. He didn’t need to compete with Lichtenstein. If someone else was doing such things—fine, let them do it.

IVAN KARP

One day in 1961 two or three young people came into Leo Castelli’s gallery, where I was working, looking for a drawing by Jasper Johns. One of them was this curious character with a shock of gray hair and a very bad complexion, who purchased after negotiations a drawing of a light bulb by Jasper Johns for the price, I believe, of three hundred fifty dollars. His name was Andy Warhol. He was very reticent and shy: he seemed extremely perceptive about what was

going on in the art world. He asked me if there was anything else of unusual interest in the gallery. I took out a painting by Roy Lichtenstein to show him. It was a painting of a girl with a beach ball held over her head. This curious little pictorial ad stI’ll appears in

The New York Times

every Sunday as an advertisement for a hotel in the Poconos.

Andy, looking at it, said in shock, “Ohhh, I’m doing work just like that myself.” Wouldn’t I come to his studio and take a look at these curious things so related to Lichtenstein’s work? Very shortly thereafter I went to this townhouse, where he had about thirty or forty paintings of various cartoon subjects, some done in the Abstract Expressionist style and some very plain and numb. He asked me for my reaction. I told him that I preferred the works without the splashes and splatterings, that if one were to work in a cartoon style like this curious character Lichtenstein, one might as well go all the way. He said he felt the same way, but that he was paying homage to the Abstract Expressionist movement with these paintings; he would prefer to reject them if he felt an audience could be responsive to work as cold and brutal as simple cartoony subjects.

Andy’s studio was a rather scrumptiously bizarre Victorian setting. The lighting was subdued, the windows all covered, and he himself sort of hovered in the shadow. He played the same piece of rock ‘n’ roll music at an incredible pitch the entire time I was there. It was a song called I Saw Linda Yesterday.” Andy told me he was playing it until he could understand it, which meant that eight hours a day he played that song at full volume.

I was fascinated by his curious and elusive presence. He was very shy about showing himself. During my subsequent visits to his house he offered me a choice of elaborately festooned masks to wear while visiting him. They covered his eyes and nose like at the

bal masqueé

of the eighteenth century. I am not one to put on a mask. I don’t know what the purpose was, but in Andy’s case I think possibly to shield his face. He never had what you would call a seemly complexion, though part of his attractiveness was the roughshod character of his face in juxtaposition to his complex sensibility. It made him almost saintly looking.

ANDREAS BROWN

He had sort of a W. C. Fields rather bulbous nose, so he had himself a nose job. A friend of mine saw him in the hospital with his face all bandaged up. Andy was embarrassed and quite angry that this guy, who had heard he was sick and wanted to

surprise him with some candy and flowers, had tracked him down at the hospital, because he was trying to do it all secretly.

EMILE DE ANTONIO

One of the driving forces behind Andy was his infatuation with celebrity. He was always writing fan letters and mash notes to people like Tab Hunter. One day he came to me and asked, “Don’t you think it would be wonderful if I had an underwear store?”

I asked, “What do you mean, an underwear store?”

“Well, well sell famous people’s underwear,” he said. “Cary Grant’s, Tab Hunter’s . . .” Andy said the underwear would cost ten dollars if it were washed and twenty-five if it weren’t.

TRUMAN CAPOTE

It had to be in the late Forties, or perhaps 1950, but certainly it was when my mother was stI’ll alive. Anyway, I started getting these letters from somebody who called himself Andy Warhol. They were, you know, fan letters. I never answer fan letters. If you do, you find yourself in a correspondence you don’t want to have; or, secondly, you find these strangers turning up on your doorstep; or, thirdly, if you don’t keep up with your letters to them after the first, they write hurt, vindictive letters wondering why you’ve stopped. But not answering these Warhol letters didn’t seem to faze him at all. I became Andy’s Shirley Temple. After a while I began getting letters from him every day! Until I became terrifically conscious of this person. Also he began sending along these drawings. They certainly weren’t like his later things. They were rather literal illustrations from stories of mine . . . at least, that’s what they were

supposed

to be. Not only that, but apparently Andy Warhol used to stand outside the building where I lived and hang around waiting to see me come in or go out of the building.