Edie (44 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

DANNY FIELDS

The New Factory was white. It was elegant. It had shiny wooden floors. It had a spectacular view. It was like moving uptown even though it was actually downtown. It was totally un-funky—minimal. It was more of a place to get things done by organization rather than by the spontaneous generation that was so much a part of the old place. There were receptionists. They were trying to keep out the maniacs. It was definitely another era.

FRED HUGHES

We tried to keep the new factory functional. About the only exception was a stuffed Great Dane we found in a junk shop. The junk dealer said it was Cecil B. De Mille’s Dog. There was a screening room in the back with big, tall doors. I was there when Andy was shot. My first thought was that it was a bomb. I got under this table. We were always frightened because the Communist Party was in the same building and somebody might throw a bomb in the wrong window.

MARIO AMAYA

It was a typical scene, people drifting in and out. There wasn’t any structure to the afternoon. I was impatient. I’d stayed on another two or three days in New York just to see Andy about the possibility of doing a retrospective abroad, and, as usual, he was very tentative about everything. So I hung around, smoking cigarettes. Several people came in and out; one of them was this woman. Nobody was in there at the time except Fred Hughes and Andy, who was over by the windows. It was a very warm day; the huge windows were all open, and I remember undoing my tie. New York had a lot of snipers at the time—we’d been reading about them in London—so when I heard these shots, I assumed that someone was shooting at us through the windows. I dropped to the ground. I heard Andy shout out: “Oh, no I Oh, not Valerie, oh, no I” I thought, “Oh, God, that girl he was talking to must have been shot!”

The next thing I remember was looking up from where I’d fallen to the ground to see what was going on, and this woman was standing over me with the gun pointed straight at me. She was wearing trousers, a jacket, and her hair was down. Luckily, she was a bad aim and the bullet grazed my back, going in and out in a very freak way, and by a miracle it missed my spine by a millimeter.

Anyway, I didn’t know what had happened. I didn’t even know I had been shot. Very odd. I remember thinking, “Oh, isn’t that lucky, she’s using BB’s instead of real bullets.” Crazy things go through your head to guard against your own fear or hysteria or whatever’s happening in your mind. Actually, the gun looked so little. Like a dinner gun . . . a woman’s gun. When those ladies were going to murder their lovers, they’d arrive in a great, long gown and a little evening purse, out of which they’d pull this tiny little gun. I looked around and saw these double doors in the back of the Factory. I said to myself, “If I can get through those doors, I’ll be all right.” Luckily, they weren’t locked.

Paul Morrissey was in the hall. He seemed very spaced out. “What’s going on? What’s going on?” He was absolutely ashen.

I said, “A crazy woman is shooting.”

We looked out through a glass window in the doors and saw the woman pointing the gun at Fred Hughes. It was absolutely terrifying. Afterwards Fred told me that he had said, “Valerie, please don’t shoot me. I’m innocent,” whatever

that

meant.

Just then the elevator which opened up into the whole space of the Factory appeared, empty—we didn’t know why or how, whether by accident or chance, or whether she pushed the button—and she beat a retreat into it.

We came out from the back, and there was Andy lying on the floor laughing. Sometimes when you’re hurt badly, you have a reverse reaction . . . an hysterical kind of laugh.

It seemed to take forever for the ambulance to arrive. They didn’t have a stretcher. Andy said something very odd: “Don’t make me laugh, it hurts too much.” No one was making any jokes. God! We finally got him down into the ambulance, and it wasn’t until then that I realized I had been shot. Someone said, “My God! Look, your coat’s torn!” I took it off, and it was soaked with blood. I thought if I was stI’ll standing I must be all right, but anyway I went in the ambulance. By this time, Andy was unconscious. He’d lost an awful lot of blood. The ambulance driver said to me, “If we sound the siren, it’ll cost five dollars extra.”

I said, “Go ahead and sound it. Leo Castelli wI’ll pay.”

The girl handed herself in. In Times Square. She claimed Andy had promised her a starring role in his next film. She headed up this thing called SCUM, the Society to Cut Up Men. She had some sort of lawyer who tried to make it a fern-lib case, saying that she had been treated badly by these awful men. Andy and I used to say that we were the first feminist casualties.

ANDY WARHOL

I was always frightened of strange people. I always thought she was strange, but one of the Women’s Lib people said she was so talented we thought, “Well, well invite her over.” I guess it was a mistake, because she was just sort of nuts.

HENRY GELDZAHLEE

When Andy was shot, my mother called me in East Hampton and asked, “Have you heard Andy was shot?” I said, “Oh, how awful! Is he all right?” She said, “They said on the radio he was in a hospital. He was shot by a girl named Valerie Solanis. Do you know her?” And I said, “Yes.” She said, “I wish you didn’t.” I said, “It’s too late, Ma.” Mothers are divine.

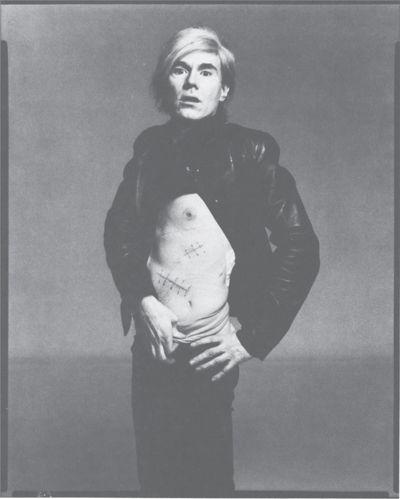

Andy Warhol, artist, New York City, 8/20/69 Photograph by Richard Avedon

Valerie Solanis was an activist early on. She’d written a script for a movie that she thought Andy should produce. When that door was slammed in her face, she just nipped.

BILLY NAME

I was in the darkroom and I heard this big bang. I came out and saw Andy lying on the floor. I was really upset. I hovered over him. I had this protector complex for Andy. I just loved him so much. When he went to the hospital, I used to go and stand outside the hospital window. I just felt like he was my own wizard.

BARBARA ROSE

On June 3, 1968, I was on the phone with Emile de Antonio and he said, “Andy’s been shot.”

I said, “Oh, D, cut it out.”

He said, “I swear, Andy’s been shot.”

I said he was crazy.

A couple of days later we were on the phone again.

I asked, “What is it?”

He said, “Bobby Kennedy’s been shot.”

I said, “That’s not possible.”

I was home alone with the baby. I couldn’t go out. My husband, Frank Stella, came back from the studio with the papers. Kennedy was critical, Andy was critical. Frank said, “Bobby’s going to the and Andy’s going to live. That’s the way the world is.”

I said, “Oh, Frank, how can you say that?”

“You’ll see,” he said. That was his essential intuition: he saw the whole thing as an American parable—a kind of real American story.

DAVID BOURDON

Andy was in the hospital with a fifty-fifty chance of survival. As soon as he was out of intensive care I got a telephone call—Andy calling me from his room. He wanted to talk. He wanted to find out what sort of press coverage he’d been getting. He knew that I was about to do an article on him for

Life

magazine, and he wanted to know how

that

was coming along. Actually, the piece had been finished and it was in the house before Andy was shot. We had all the photographs, the layout, everything. Then Andy was shot. The

Life

editors were ecstatic. It was going to be a lead story—eight or ten pages—a major space in the following issue.

But then Robert Kennedy got shot. Andy’s story was killed, and the cover story came out on the Senator . . . which was the obvious choice. The following week the Andy story was much less exciting to the editors, and they said to me, “Well, the only reason to run the story now would be if Andy . . . you know . . . died.”

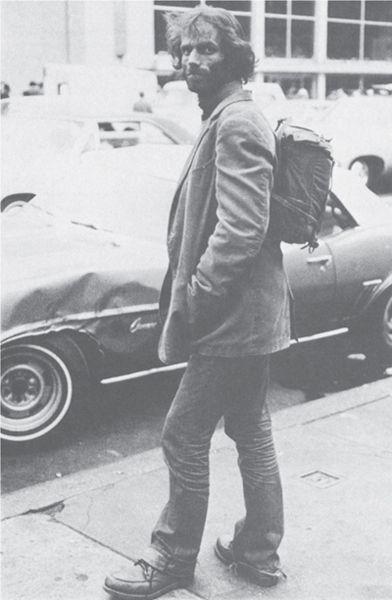

Billy Name leaving the Factory

So Andy kept calling me up: “Are they going to run the story this week?”

I told him, “Andy, they’re very mean. They’ll only run the story if you die. I’d much rather have you alive, even if it means that my story doesn’t get published.”

Andy wouldn’t believe me. He kept saying, “Oh-h-h, can’t you get it in anyway?” He wanted it both ways.

PATRICK O’HIGGINS

I saw the scars on his stomach. Avedon took a picture of them and they show up black on white. But when you actually see them, these ghastly tracks and scars and holes are white on white—white on that pale stomach of his. No red welts. Pale, pale as could be. Not a hair. I think he’s an albino.

BARBARA KOSE

He became another person after the shooting. He didn’t take another risk after that. Up until that time he lived a life of extreme risk. There’s no question the shooting was a suicide attempt; he provoked it. He was waiting to be shot. Oh, the whole thing was set up for Andy to be killed. It was part of the kind of closet theater that went on there. It was inevitable, absolutely inevitable.

JEAN STEIN

When Henry Geldzahler and I went to visit Andy at the Factory we talked for a while about the Sixties. Andy said, “We saw so much of the Vietnam War because it came up and down Forty-seventh Street. The demonstrations went right past the Factory on the way to the United Nations.” I asked him about sin. Andy sat quietly staring at the table: “I don’t know what sin is.” He paused, then turned to Henry, “What is sin, Henry?”

TAYLOR MEAD

Andy died when Valerie Solanis shot him. He’s just somebody to have at your dinner table now. Charming, but he’s the ghost of a genius. Just a ghost, a walking ghost.

PATTI SMITH

They always talk about the end. I guess that’s when they pulled the silver down from the wall.

JOEL SCHUMACHER

After Edie split with Andy and the Dylan thing collapsed, she desperately wanted to model. She looked so incredible at that period . . . not unlike Twiggy, but much sexier and much more the American girl.

She was the total essence of the fragmentation, the explosion, the uncertainty, the madness that we all lived through in the Sixties. The more outrageous you were, the more of a hero you became. With clothes, it was almost a contest to see who could come out with the most outrageous thing next. “I’m going to make a dress out of neon signs.” “Oh, well, I’m going to make one out of tin cans!” “Oh, yeah? You

are

? I’m going to make one out of sponges I” “Oh, yeah? Well, I’m going to make one out of a

toilet.

”

And then everyone would fight over who was going to wear these things. I remember we opened a Paraphernalia shop in Cleveland, Ohio, and for the opening fashion show I had done a dress of mirrors. There was another dress with the word love cut out down the front of it. A couple of the girls began fighting over who was going to wear what. Marisa Berenson was very upset she wasn’t going to wear the mirror dress.

So you had to show these things off, and not only that, but you had to do it all night. You had to dance . . . and you had to dance fabulously. And everything you read—every paper, magazine—told

you how fabulous it was to be young; youth was

it

. And so you had your mother and your grandmother wearing tin-can garbage dresses with red metallic fishnet hose, and they were trying to go out all night and do that sort of thing, too.