Edie (46 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

I’m a little nervous about saying anything about “the Artist? because it kind of sticks him right between the eyes, but he deserves it. Warhol really fucked up a great many people’s—young people’s—lives. My introduction to heavy drugs came through the Factory. I liked the introduction to drugs I received. I was a good target for the scene; I blossomed into a healthy young drug addict.

GERARD MALANGA

This is what I wrote about Edie in my diary on Monday, October 17,1966:

. . . Call Edie . . . Edie invites me over. I’ve never seen her more beautiful. She puts on a pair of red leotards and a red tight cotton top. I weed out the seeds and twigs from the pot and fI’ll one-eighth full Camel with the Acapulco Gold. We get extremely high. She tells me how she wanted to run away from the mad publicity for an entire year, how it all frightened her, how transparent it all was, and how some of them are so desperate for the faceless publicity—stark raving mad seeking acquisition they want so desperately. How sorry Edie feels for them. How composed she remains . . . I leave Edie falling asleep in her apartment. . . .

And here’s what I wrote two days later:

Got up at eleven, picked up silk screen transparencies and bring them up to Andy for inspection, visit Edie in Lenox HI’ll Hospital who two days earlier, having left her falling asleep, her apartment caught fire.

GEOFFREY GATES

At about eleven-thirty one night I got a call from Mary Ann Nordemann, who lived across the street—an old friend of mine—screaming in my telephone, “Get up, your house is on fire!” I yelled and jumped out of bed to run for my door. I saw smoke hanging around in my apartment. Just as I reached the door, it disintegrated. Fireman Hennessey, who seemed about eight feet tall, had been knocking on my door and simply decided to come on through, which he did. Just a shower of wood and a huge fireman there.

Apparently Edie had taken an overdose of something, let a cigarette go, and when the fire started, she was lucky enough to make it out of the apartment. It was a very intense fire. I don’t know what was burning in there—maybe the rhino. She had been taken off to the hospital. I found a

Social Register

in someone’s apartment and tried to reach a Sedgwick somewhere to tell them what had happened. From Santa Barbara I was given a very nervous brush-off by whoever answered the phone. Another Sedgwick in Massachusetts just totally freaked out. He just didn’t want to hear about it. “I have no interest whatsoever in this matter.” That was one of the nightmare aspects of the whole episode—calling up these known relatives and being told there was no interest whatsoever. Finally I reached her uncle, who happened to be here in New York from Boston. Minturn. He was pretty distressed, and dealt with the situation.

MINTURN SEDGWICK

I was in New York staying with friends and my hostess—a highly intelligent and very nice person—received the phone call; instead of rushing to my room, she took the precaution of calling the Lenox HI’ll Hospital beforehand to find out how Edie was. She was off the danger list. I went to the hospital the next morning to see her. She looked fine. She was lucky; just a bandage on the inside of her arm.

Edie looked very cute. Perfectly lovely. I asked, “Is there anything I can do for you?” She said, “Bring me my make-up.” She gave me a list as long as your arm.

I ordered it from the hospital pharmacy, paid for it, and sent it up. When I came back at five in the afternoon, she’d put it on—dark stuff here and there—and she suddenly looked like a death’s head.

JANE FIELD

I asked Mr. Gates, who lived opposite Miss Sedgwick, if I could put her furs and clothes in his apartment. I worked for Mr. Gates, but I’d come in from time to time—a few times a week—to clean up her apartment. Sometimes Miss Sedgwick would tell me her problems. She told me about one man—the man she was in love with. He’d walked into a nightclub with another woman. She had tears in her eyes when she told me about it. All I could do was tell her to pray.

Sometimes she’d have tears in her eyes and then I’d have tears in mine. I always felt helpless because I couldn’t help her. She was so generous. She paid me more than it was worth. I’d say, “Oh, you don’t have to do that!”

“Oh, take it, Jane.” She’d practically force it on me. “You’ve cleaned up. It was such a mess.”

She had gobs and gobs of pills. One day I went in there to do some cleaning. What I saw made me close the door and go away. She was sitting on the floor with all these pills around her like in a half-circle . . . cross-legged in a sea of pills. She was in a dopey mood. I stayed there long enough to see her reaching for one, and I left.

While I was working in her apartment after the fire, these two men came creeping up the stairs and began rummaging through her closets and drawers. They had no underpants on and you could see their heinies through the holes in their blue jeans. They acted like leeches. Maybe they got away with some of her clothes and glass ashtrays.

JUDY FEIFFER

Edie claimed she was lighting candles when the drapes caught on fire. She lit candles every night . . . on the mantelpiece . . . like a child who doesn’t want to sleep in the dark.

I went to visit her in Lenox Hill. She was frantic to get out. She responded to that hospital like some mad, frenzied small animal. She was going to call the cops. At all cost, at any cost, whoever was on the board of directors, whatever her contacts were, whoever she knew, she was going to get out of that hospital, and that day. She began a high-pitched campaign and she got out. Twenty-four hours—that was it. She knew the way to get out.

EDIE SEDGWICK

(from

Ondine and Edie)

It’s

a wicked hospital. I got stuck in there with seven women, all Jewish, all old, all screaming: they wanted flowers, cookies; they wanted their children to come and visit. And waking up with someone having an operation right next to me. I couldn’t move because I had the tube in my mouth and the tube in my fluid evacuation. They wouldn’t give me anything to put me to sleep. You get used to these things. I had to hear them all night. One of them recited . . . it was like a tiger licking.

JUDY FEIFFER

After she got out of the hospital, she said to me, “I have an accident about every two years, and one day it won’t be an accident.”

BOB NEUWIRTH

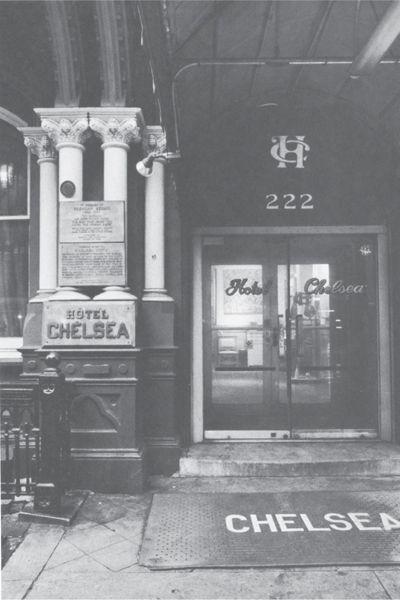

After the fire, Edie moved to the Chelsea Hotel on West Twenty-third. I think she went there because of its sense of tradition and historical impact, and also the artistic milieu. I’m sure her family wanted her to live uptown at the Barbizon Hotel for Women. There were other people in town who wanted her to live at the Sherry Netherland. But the Chelsea gave her a sense of freedom, of artistic license. She knew everybody who lived on her floor, and on all the other floors. She was a star there . . . like Kay Thompson when she lived at the Plaza and wrote

Eloise.

Edie was the genius in residence.

VIRGIL THOMSON

The lobby of the Chelsea used to have very large, exuberant pictures of the Hudson River landscape school. It had perfectly enormous black furniture with leather upholstery. In the middle was a round settee with a pyramid in the center and a palm on the top of it. Of course, now the lobby is falling apart . . . pretty dingy.

Everybody’s lived here at one time or another—usually when they were young but not famous. Tennessee Williams, Thomas Wolfe, Dylan Thomas, Arthur Miller, Edgar Lee Masters, who was my next-door neighbor, and Gore Vidal. All were here, most of them unknown, at different times. I met Bob Dylan here once. That’s when I discovered, much to my surprise, that though he sounds in recordings like a real lowdown Southern mountaineer, he is a perfectly nice Jewish high-school graduate from Hibbing, Minnesota, who speaks correctly and with manners. His public personality is one purely assumed on his part.

For a long time the traveling rock bands stayed here. You could tell they were rock bands because they wore their concert clothes—purple velvet pants—all day long to get them dirty.

From time to time there do appear the most sensational Negro pimps, very tall, and with high heels, slender, with the most beautiful tailoring, and picture hats, wide picture hats. Every now and then they get put out. If they get themselves into the dope trade, they always get put out.

Of course, one of the happier attributes of the Hotel Chelsea was that it was so inexpensive. The St. Regis was about forty dollars a room in the Sixties. A single room in the Chelsea could be had then for twenty dollars. It would have been a good place for someone with financial problems.

BOB NEUWIRTH

Edie got cut off about the time she started living in the Chelsea—no more allowance—so we got her a professional money manager, Seymour Rosen. He advised her . . . not a young guy, but a middle-aged man who took care of money matters for a lot of show-business people. He got her bills in order; he lined up her creditors and got them not to sue. He tried to get her family to contribute to the easing of the financial situation, but at that point they weren’t ready to trust anybody.

So she had no money coming in. The only people she had to turn to were people from her own social circle; some of them were generous and some weren’t. To give Edie a check for a thousand dollars was like giving most people ten. Very hard to envy Seymour Rosen his job. He really adored her.

SEYMOUR ROSEN

I visited Edie from time to time, and then she would come by to see me, depending on her needs. Maybe two or three times a week she’d come by to say hello, and to steal fountain pens, just for a lark, apparently: she had a thing about them; she stole all the fountain pens off my desk.

I remember those times when we went down to the Fiduciary Trust. She looked like a twelve-year-old boy. Asexual. We took the wrong elevator at the bank one day and ended up in the record-keeping department. Everybody was working at the accounting machines and calculators. She was dressed in her usual style. We walked through there; everything stopped. She was wearing what came to be called Capri pants. Nobody was wearing them yet. The hip-huggers. Bare midriff. People weren’t even wearing them on the beaches. Really stopped traffic at the bank. We met with an officer. We were sitting across from his desk, and he kept staring at

me.

He couldn’t look at her, he was so embarrassed. They’re a very conservative, straight-line, Wasp organization . . . really old-line.

She couldn’t travel on public transportation. Just couldn’t handle it. Only by limousine. I took her on a bus one day just to try to get her to learn how to use it. She got off after a few blocks and called for the limo. Not even a cab! Bill’s Limo Service. She was clutching me. Very, very uncomfortable and nervous.

So I would take care of Bill’s Limo. I tried to keep the creditors in line by doling out as little as I could to keep them happy. Some of them were very nice. Cambridge Chemists. Lovely, lovely people: souls of compassion. Also the place across from Lincoln Center, the Ginger

Man. They, too. She was into them for quite a bit. We worked out a payment. People were nice to her. I think it was those eyes.

Occasionally Edie would throw a fit. She’d call up, screaming hysterically on the phone, to ask for one hundred fifty to two hundred dollars

instantly.

Conceivably, she was fighting with her connection. Once there was a big scene in a hotel lobby—big, messy scene—and I had to send somebody over there with a few hundred dollars to quiet things down.

Her mother was very concerned about Edie’s welfare. Once I met with her when she came to see Edie in the Chelsea. The Chelsea’s a very depressing place, to begin with. Her mother wanted her out of there. I remember she kept talking about the ranch: why didn’t Edie come out? I thought her mother was a hell of a nice lady. She was very solicitous toward Edie, plumping pillows, smoothing her hair, and Edie was reacting the way most daughters do when a mother is solicitous.

BOB NEUWIRTH.

She’d been in the Chelsea for a few months when she went home to Santa Barbara for the Christmas of 1966—a magical time for all loonies anyway—to visit her parents. It was an unfortunate idea. They had some queer old New England Wasp family idea of, well, it’s okay if she spends thirty thousand dollars the first year and forty thousand dollars the second year as long as she gets married the third year and gets herself suitably taken care of for the rest of her life. But when it appeared that she was not going to get herself a nice young polo player, and didn’t want to either, it became a question of her parents’ not being able to afford to have her independent.