Edie (54 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

ANN MORRISON

Toward the end Duke became much more Catholic in feeling. In fact, a Catholic priest, Father Virgil, saw him just before he died and gave him the last rites. There was a big Catholic service in the Santa Barbara Mission.

JANE WYATT

Duke died on October 24, 1967. Father Virgil officiated at his funeral service. The Santa Barbara Mission was absolutely jammed to the very last pew. They had a perfectly beautiful service. The priest said wonderful things about Duke—about all the different facets of being a husband, a writer, a financier, a painter, a sculptor, a rancher, and so on. The music came from a man up in the choir loft. They thought of having monks singing from up there, but they had a single man with either a harmonica or a guitar playing cowboy laments—There’s a Long, Long Trail,” or “Get Along, Little Dogies.” The tears were just rolling down everyone’s face.

SUKY SEDGWICK

Mummy was absolutely stoical . . . in fact, Mummy is that way. Since that time I’ve gone back, and she reads Shakespeare and cries, and that just distresses me, because I know if Mummy can cry that means the dam is overflowing. She’ll be all right, but she’s got so much behind her that . . . that it just topples over the top of that tremendously enormous barrier.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

My father asked me to do three things. One, to take care of my mother; two, to scatter his ashes on the ranch . . . I can’t remember what the third was. I got part of it done—spreading

the ashes. I traveled across the mountain with this little box that used to be my father which weighed about fifteen pounds. I had the awareness that he was there with me. I found a place where I could do it, and I threw the ashes into (he wind. Into the wind, man, and a lot of it came back into my face, in my mouth, and I was

eating

my father. That was the weirdest trip I’ve ever been through in my life. I couldn’t get it all out! It was like tons of it went in my mourn. It was weird. Of those three things he asked me to do . . . well, I didn’t do anything but scatter the ashes. I wish I could remember what that third thing was.

RENÉ RICARD

Edie was in Gracie Square Hospital when her father died. Everyone said, “Fuzzy’s dead . . . finally. Thank God. Now maybe Edie can breathe.” But it didn’t have that effect on her. It was a heavier weight. She kept going in and out of hospitals.

One of my theories is that Edie never had to worry about what she was doing or what was going to happen to her because she always knew the bins were there in which to collapse. I never heard her speak badly about the bins, you know. That’s the sad thing. She was convinced that they were necessary and helpful.

L. M. KIT CARSON

I had written a film called

August September

about a rock ‘n’ roll assassination and I wanted Edie to be in it. A lot of good people were involved in the film. Michael Pollard, who had just made

Bonnie and Clyde,

was in the film. He had met Edie in California and he was in love with her, mostly because he knew Edie had been involved with Bobby Dylan. Michael was in a semi-Dylan phase at the time. By the time she was in Gracie Square other people in the film were in love with her—the director, the producer’s lawyer—a guy named Bob Levine who is a very straight kind of lawyer. One day he brought her flowers and then stepped out of the room, dashing tears from his eyes because she was so beautiful and there was so much obviously there.

When they let her out, we began living together. One thing I remember . . . well, how she smelled. In sex your body takes on a certain odor. Edie had a particular smell that came out in lovemaking . . . a sweet but somewhat sickly smell, like orchids. I always thought it had something to do with her burns and the chemicals involved in reconstituting her body. To fuck her was like fucking a very strong child, a twelve-year-old girl . . . athletic and coltish.

We finally moved into the Warwick Hotel, registering there as Mr. and Mrs. Carson because she was afraid they wouldn’t let her in under her own name. She thought she was on a hotel blacklist for burning her room in the Chelsea. She had kept me up for about a week straight. Then one day in the back of the toilet I found the little plastic top they put on hypodermic needles, and I realized she was on speed. I really got pissed off. I had a kind of messianic Jesus Christ complex . . . getting involved with girls who are victims and trying to save them. So I got the drugs and took them away from her. We stayed there for two more days without her being allowed to shoot up, and I watched her disintegrate. I had to hold her down on the bed; she writhed; she bounced off the walls. She turned from being Edie, this beautiful woman, into a monkey. It got very violent. We were both being violent, threatening to jump out the windows and kI’ll each other. I told her I was going to kI’ll myself if she didn’t stop it. I guess I was trying to make myself into the victim that she would have to save, turning into Edie Sedgwick, doing an Edie Sedgwick number. She got insulted because I was threatening her.

Finally I called her doctor and said, “She’s driving me crazy.” I told him I was losing a lot of weight, and that I was a wreck. I was over the edge. “What can I do?” I told him I couldn’t take care of her and she wouldn’t voluntarily commit herself anyplace any more.

He said, “Leave. Get out!”

I was at that state where that was all I could do. I called Warhol and got a hold of Ondine to come and take care of her. Andy wouldn’t do it. He just couldn’t handle it. But Ondine was enough of a monster to handle Edie, who was another monster. One speed freak knows a lot about another. So he got on the phone and he screamed at her and she screamed at him, but they were having a great game: she was finally being handled by somebody who knew exactly what she was up to.

Then three minor Warhol people came up to the room, but not Ondine. They got all the dope she had in the room and laid it out on the bed. They had a funny way of handling it . . . opening up the

capsules on the bed and tasting the stuff and saying how great it was, really good speed, and chiding her for not letting them know that she had all this stuff. They were packing it up to use—right? They said to me, “Okay, well take care of her. Go ahead and leave.” Edie was delighted, because she thought she was among friends; I guess she’d gotten tired of pushing me around and playing tricks on me.

So I left. I got on a plane and went back to Texas and went to sleep for a couple of days. Three or four days later the police came to the house in Texas and said they’d gotten a call from the manager of the Warwick Hotel in New York saying that my wife was in Bellevue Hospital.

New York Post, May 2, 1968

EDIE SEDGWICK: WHERE THE ROAD LED

by Helen Dudar

It’s hard to keep track of the leading ladies on the pop scene—they come and go so fast that nobody ever stops to wonder what happened to last year’s girl. Or even last week’s girl.

Like, who has lately thought “Whatever happened to Edie Sedgwick?” Edie Sedgwick, the 1965 girl. After Baby Jane Holzer and before Viva. Youthquaker! Superstar! The girl Andy Warhol was never without. The one with great brown liquid eyes, who silvered her hair to match his and flickered through half his movies and went to all the good parties with him.

It was Viva, this moment’s Warhol superstar who mentioned in a

New York

magazine interview that Edie was “in the hospital,” and had been for a long time. Viva said she had visited her there.

Later, on the telephone, Viva identified “there” as Gracie Square Hospital, a small, private, discreet establishment on the Upper East Side, whose patients are usually well-to-do and desirous of private, discreet care. . . .

Gracie Sq. Hospital: The switchboard operator reports “She’s not here.” WI’ll not say whether she had ever been there.

Chelsea Hotel: . . . She left nine months ago. No forwarding address.

Viva: Then a.m. call awakened her, and her voice is a suffering whisper. “None of us know where she is now.”

Andy Warhol: I don’t really know where she is. We really were never that close. She left us a long time ago.”

The caller, remembering pictures of Andy and Edie at this, that and the other thing, persists, “But there was a time when she was with you a lot.”

“Yeah, but then she went on her own and we never saw her any more.”

“Do you know of any friends who might know where she is?”

“Well, she went with Albert Grossman, you know, Dylan’s manager. That’s a whole different crowd. But I never really knew her very well.”

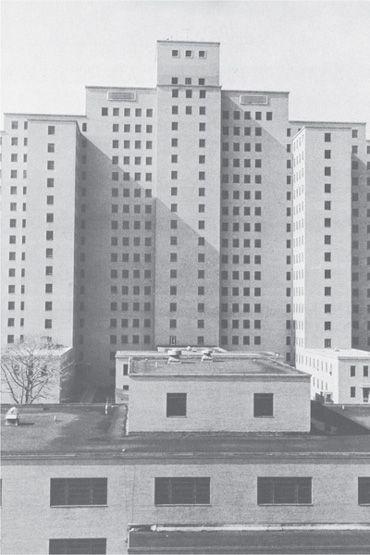

Manhattan State Hospital

Manhattan State Hospital

EDIE SEDGWICK

(from tapes for the movie

Ciao!Manhattan) “The Siege of the Warwick Hotel.” I was left alone with a substantial supply of speed. I started having strange, convulsive behavior. I was shooting up every half-hour . . . thinking that with each fresh shot Td knock this nonsense out of my system. I’d entertain myself hanging on to the bathroom sink with my hind feet stopped up against the door, trying to hold myself steady enough so I wouldn’t crack my stupid skull open. I entertained myself by making a tape

. . . a

really fabulous tape in which I made up five different personalities. I realized that I had to get barbiturates in order to stop the convulsions, which lasted eight hours.

Something was spinning in my head.

. . . I

just kept thinking that if I could pop enough speed I’d knock the daylights out of my system and none of this nonsense would go on. None of this flatting around and moaning, sweating like a pig, and

whew!

It was a heavy scene. When I finally cooled down to what I thought was pretty good shape, I slipped on a little muu-muu, ran down the stairs of the Warwick, barefoot, to the lobby. My eye caught a mailman’s jacket and a sack of mail hanging across the back of a chair in the hallway entrance, and before I knew what I was doing, I whipped on the jacket, flipped the bag over my shoulder, and flew out the door, whistling a happy tune. Suddenly I thought: “My God! This is a federal offense. Fooling around with the mail.” So I turned around and rushed back and

BAM

!

the manager was waiting for me. He ordered me into the back office. They telephoned an ambulance from Bellevue and packed me into it. Five policemen. I was back into convulsions again, which was really a drag, and I tried to tell the doctors and the nurses and the student interns that I’d run out of barbiturates and overshot speed.

. . . I

could speak sanely, but all my motor nerves were going crazy wild. It looked like I was out of my mind. If you had seen me, you wouldn’t have bothered to listen, and none of them did.

Oh, God, it was a nightmare. Finally six big spade attendants came and held me down on a stretcher. They terrified me . . . their force against mine. I got twice as bad. I just flipped. I told them if they’d just let go of me, I would calm down and stop kicking and fighting. But they wouldn’t listen and they started to tell each other what stages of hallucinations I was in . . . how I imagined myself an animal. All these things totally unreal to my mind and just guesses on their part. Oh, it was insane. Then they plunged a great needle into my butt and

BAM

! I

out I went for two whole days.

When I woke up, wow I Rats all over the floor, waiting and screaming.

We ate potatoes with spoons. The doctors at Bellevue finally contacted my private physician, and after five days he came and got me out. They sent me back to Grade Square, a private mental hospital that cost a thousand dollars a week. I was there for five months. Then I ran away with a patient and we went to an apartment in the Seventies somewhere which belonged to another patient in the hospital, who gave us the keys. The guy I ran away with was twenty, but he’d been a junkie since the age of nine, so he was pretty emotionally retarded and something of a drag. I didn’t have any pills, so, kind of ravaging around, I went to see a gynecologist and a pretty well-off one. He asked me if I would like to shoot up some acid with him. I hadn’t much experience with acid, but I wasn’t afraid. He closed his office at five, and we took off in his Aston Martin and drove up the coast . . . no, what’s the name of that river? The Hudson.

We stopped at a motel and he gave me three ampules of liquid Sandoz acid, intravenously, mainlining, and he gave himself the same amount and he completely flipped, I was hallucinating and trying to tell him what I was seeing. I’d say, “I see rich, embroidered curtains, and 1 see people moving in the background. Its the Middle Ages and I am a princess” and I told him he was some sort of royalty.