Edie (53 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

RICHARD LEACOCK

I called Edie in August, 1967, and asked her to play the part of Lulu in the film sequences for Alban Berg’s opera, which Sarah Caldwell of the Boston Opera Company had asked me to do. I bought Edie an airplane ticket and she arrived first-class with a bandaged bare foot and what looked like a nightgown on. She was absolutely desperate because she had been on some drug, and if she withdrew from it she would have convulsions. Everybody had to run around like crazy to get what it was she needed. About four in the morning she decided she wanted a chocolate milkshake with two scoops of ice cream and an extra blob of something else. I adored her from afar. For those closer to her it was more complicated. I asked Bobby Neuwirth to come along with us on this filming—in a sense I saw him as a nurse, which was not really fair because it drove him crazy. I remember him saying, “Don’t ask me to be a nursemaid. I can’t do it. I can’t take it.”

Edie had never read the script, never heard of

Lulu

, had no idea what it was all about. I was certainly taking advantage of the fact that she was living through this.

SARAH CALDWELL

Ricky Leacock and I wanted to try to use some of the techniques of the Czechoslovakian film and theater—of the actors walking from the stage and onto the screen and off the screen and onto the stage. But mostly we wanted to capture the essence of Lulu in a way that is very difficult to do without the use of closeups. The unreal images of Lulu, the frightening things that one didn’t even want to talk about, could be shown more clearly on the film than they could be shown in life.

Ricky went to find Sedgwick and we used five or six film sequences in the opera which he did with her. He started shooting them as very literal film and then he filmed the images reflected on Mylar, which produced a strange image that came and went. So the deeper one got into Lulu, and the stranger her whole relationship to the world became, the further out the film was.

Before the opera, when the public began to come in, the actors turned on some films and sat down to watch. Animalistic films. We had an incredible film of a snake swallowing a rat. There was a scene of a lioness chewing some raw meat which is just one of the most “ugh” kind of things. One member of the animal kingdom feeding on another. And a few nice death scenes. It was brutality.

We were trying to set a mood. The opera starts with a ringmaster in a circus who announces that this is a play about animals. And then

the animals turn into people. Each character has its animal correspondent. They are tigers, bears, monkeys, lizards, and earthworms. Lulu is a serpent.

Sometimes the audience got very involved and went up on stage to ask the actors why they were showing the films. They would answer: “Why do you think we’re doing it? Would you like to see that again?” And the actors would turn back and show something particularly horrible. The audience is watching a horrible play unfold. But enjoying it. Enjoying it as Lulu destroys each one of the men in her life until finally she is destroyed. But there’s no question that in the audience there’s a sense of almost relish as these things happen, which is another frightening comment on the piece and how it affects people.

Lulu ends up as a prostitute in London, where Schigolch, the old man who pretends to be her father—he’s really the first man in her life—becomes her pimp. After Lulu solicits Jack the Ripper, a closeup of his face on the screen reveals that he is Dr. Schön—the man who earlier in the opera gave Lulu a gun and tried to get her to commit suicide. . . . She killed him instead. The final scene is very dark, but I remember vividly his killing her and cutting her into nice little pieces. On the screen the audience could see the shimmering, distorted image of Edie’s head with a red wig on a greenish-white sheet, and then slowly a huge pool of blood spreads around her head.

Lulu is finally destroyed. But you can’t wipe out the Lulus of the world. They go on.

BOBBY ANDERSEN

After

Lulu,

Edith returned to New York. I knew she wanted to see her father before he died—all those trumped-up fantasies about going out to California to visit him when she lived with me at Margouleff’s. She kept telling me how they had kept him alive for a year on depressants and painkillers and he was withering away with cancer.

Edith would ask her mother if she could talk to her father, but he wouldn’t come to the phone. Mrs. Sedgwick would say, “Your father has to do this . . . he has to do that . . . he isn’t feeling well. Edith, you don’t know what you’re doing to your father.” All she ever got was “your father, your father, your father.” Just hammered up her back.

Edith begged. Cried. Quite a few times. He would

not

speak to her. She had so many mixed, tortured emotions about that man. She loved him, she worshiped him; she hated him.

Her mother would say, “He can’t come to the phone. Edith, please, don’t put me through this.”

Sometimes Edith would wait until she’d hung up and then she’d cry. Sometimes she’d get really furious and outraged and scream about it. She’d turn cold and clinical as she’d describe her childhood and the things they’d done to her.

She told me that her father once tried to punish her by taking her

out to the corral, tying her to a post, and whipping her in front of all the servants and the ranch help. She made her father sound like a sadistic Bluebeard, how incredibly unbearable and cruel he was . . . I’m sure she was exaggerating, because people on amphetamine tend to do that a lot. For example, she showed me all these fabulous equestrian sculptures that I now understand her father did and said that

she

had done them . . . pulling out these photographs of enormous sculptures to show me. In those days I just didn’t think it was possible for people to sit and fabricate things like that, so I was very impressed and awed. I kept saying: “You really did that? You did that yourself? With your little hands and your little body and your little person?” She kept saying, “Oh, and you should have seen some of the other things I’ve given away to doctors at the hospitals where I’ve stayed.” Well, that’s an amphetamine thing . . . to fib. It could show a desire to duplicate her father in herself, couldn’t it?

She had her children’s books with her . . . her name inside in scratchy little handwriting. Nursery storybooks . . . most of them English imports from these smart little California bookshops. She cherished them. This is from this time of my life . . . these are from my childhood when I was a little girl.”

She showed me other photographs. “This is my home, this is from my childhood, this is my father’s . . . this is my mother’s . . .” Home, home, home, home. All I heard about was the name of the ranch: Laguna, Laguna, Laguna. Her horses. How big and wonderful it all was.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

The ranches always seemed to have one great fat oak tree that was the center of things—the houses sort of curled around them. Incredible trees. We figured they went back to the time of Columbus. At Rancho Laguna, the tree there had wide branches that sheltered Edie’s room. It had periwinkle underneath it, very green, which the dogs loved to romp in. It was beautiful. It was like the centerpiece of the family. I know fuzzy pumped a lot of money into keeping that tree alive. William Kennedy, the butler, told me he spent twenty thousand dollars. One time when I came back from Groton, my father and I were walking by the tree. Just then my father looked up: “You know, when that tree dies, 111 die.” That stuck in my mind. I tend to see symbolism in things. When I went back to the old ranch at Corral de Quati, I noticed the tree there had been tremendously pruned—big limbs were missing.

SAUCIE SEDGWICK

My father was rushed to the Cottage Hospital in the middle of the night with what they thought was a kidney stone. They did an operation and found out he had cancer of the pancreas. It’s known as “silent cancer” because by the time you have any symptoms it’s too late. The cancer had eaten through some tubes that work the kidneys. The following summer he needed another operation.

He did another sculpture: St. Francis receiving the stigmata. Everyone said he was absolutely heroic. Kate told me that he kept trying to do those exercises of his. It must have been like watching an animal whose back is broken. She said it was painful to see because he didn’t have the strength to do much except to keep going as best he could.

What stopped him was his sons’ deaths. I think he was just eaten alive with guilt. He abused them both terribly, but he must have thought that they would survive and become what he wanted them to be. He had always kept illness at bay, but the moment the real thing—death—got into his family, he died.

HARRY SEDGWICK

Fuzzy suddenly realized he’d destroyed people. He sent out a Christmas card with some Greek saint, or some character in song and story, who apparently had destroyed his children. Killed them all. Alice stopped the mailing but a few did get out. I know there was great talk in the family about it.

MINTURN SEDGWICK

I went to stay with Francis and Alice near the end of Francis’ life. I heard him say, “You know, my children all believe that their difficulties stem from me. And I agree. I think they do.” I can see him saying it just casually to me—I think there may even have been other people there. He stated it; he felt it; he knew it.

SARA THOMAS

He never sounded afraid or in despair. When Duke talked on the phone, he always sounded like himself. Once in a while when I called him, he’d say, “It’s not a good time.” But he always had a vaguely jaunty way of talking about things like that, so it didn’t embarrass me to talk with him about it. You never got the feeling that he was afraid of dying. Or. that he didn’t believe he was going to.

But he did worry about his wife. He said, “I don’t know what’s going to happen when I’m not there to organize the ranch. I hate to leave her. She tells me she won’t leave it. I don’t want her to stay there with all those memories.”

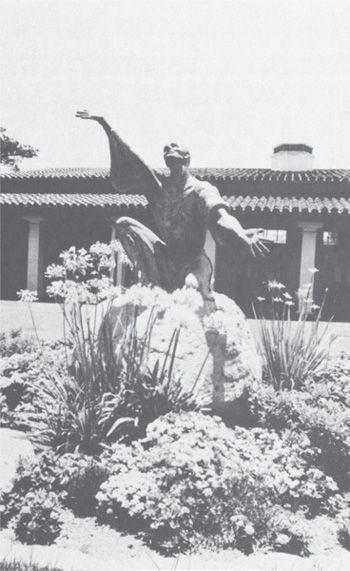

The statue of St. Francis by Francis Sedgwick at Mission Santa Barbara

HELEN BRANSFORD

He may have had

some

concern for Mrs. Sedgwick—I mean, obviously he would—but he was the same old Duke to the end. Friends of the Sedgwicks were shocked because he took up with a young married woman, Ann Morrison, from a first-generation Catholic background. Her father is now a successful businessman in Santa Barbara.

HOLLY HAVERHILL

Ann Morrison saw a lot of Duke toward the end of his life. She’s really smart as a whip. What was involved with Ann and Duke I had no idea. Naturally everyone in a small town like Santa Barbara has a different story. She’s extremely attractive. She’s always gone directly after what she’s wanted. Sexual energy. She’s terribly interested in clothes—able to be chic, or easy and casual in blue jeans. They never made any pretense about their interest in each other—Duke and Ann. You’d meet them having lunch together, walking down the street arm in arm. She was obviously a person who made him

feel

better; he had fun talking to her.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

In one year my father aged forty years. Just a shrunken little old man. Absolutely white hair! When I went to the hospital, I had no feeling, man. He wouldn’t let me give him love! So what could I do? I wasn’t going to sit there and just say, “Well, the weather’s fine today.” So I said, “Ah, that must be a bummer having nothing inside you but tubes.” He went, “Yeah.” I wanted to say, “Why the hell are you trying to stay alive?” I could talk to him square-out. No love. Like, when I first knew he had cancer and we were out riding, I said, “Must be really strange to know you’re going to the in a couple of months.” He said, “Yeah. It’s pretty heavy.” That’s all he said.

In the hospital he wanted Ann. My mother was shut out. The person who cared the most was Ann. She had access to my father at any hour. My sister Pamela tried to keep her out, but couldn’t. She went and read to him every day.

ANN MORRISON

We read short stories—Balzac, Stendhal. He loved to read. He was always correcting my English. He could tell stories, stories about people he knew all over the world, and he would tell them in a very Harvard-like way, every sentence structured beautifully so it made the listener chuckle and laugh.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

My father’s way of letting out his pain was with laughter or by telling people his troubles . . . just blurting them out. It embarrassed and upset my mother, because she didn’t like family things to be heard by everybody. He’d tell everybody, with a sort of nervous laugh, that Minty had hung himself and that Bobby had destroyed himself on a motorcycle. Then, just before my father died, he gave this sculpture to the mission in Santa Barbara. It was of St. Francis receiving the double stigmata. St. Francis was really him. He never liked his name, Francis. So maybe he was purifying it by putting the “Saint” in front of it. He dedicated that statue to the memory of my two brothers. I think it was a way of purging his guilt. Even though you build up a lot of bad karma, you can get rid of it by giving.