Edie (56 page)

Authors: Jean Stein

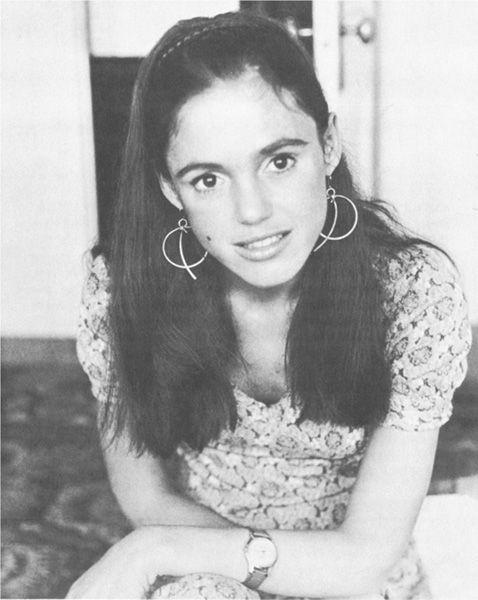

I was hanging out on the streets of Isla Vista. I met Edie and we just kind of clicked . . . both Aries, and we got off on each other—getting really spaced, just partying and having a good time. The first time I met her she wasn’t dressed like the others, who were wearing East Indian tablecloths for dresses and raggedy Levi’s. She wore high heels, short skirts, big earrings, and a hat like out of a fashion magazine. But then she started wearing what the others wore. She had a real pretty, innocent face, out of character there . . . like a debutante wearing biker clothes . . . Levi jackets. I fell in love with her at first sight. Man, look at this person—she’s perfect! She was so friendly. Ready for anything. Unreal. In the mornings she’d watch the soap operas on TV and I’d watch

her.

The entrance to Rancho La Laguna

People on the street weren’t too much into staying clean or healthy. Drugs were the first thing. A lot of people liked to drink. And then the eating would be jelly doughnuts. The streets were basically a bunch of people who couldn’t make it anywhere else and ended up there getting spaced.

She was always doing just what she wanted. We’d walk into the Sun and Earth together, over to the juice counter, and she’d ask: “I wonder what this tastes like?” She’d open up a bottle and take a drink—”Eeeech!“—put it back, and walk out. Things like that just shocked me. Very presumptuous.

She was flighty like . . . she’d just run off with some other guy. Once in the mountains we went to a party where everybody got real drunk on wine. Edie kept running off with this other dude, and I’d get real pissed. She’d try to tell me, “Hey, it’s cool, man.” “Ifs not cool!” “Ifs cool.” It really blew my mind. There was this guy Bob Brown, a musician, big guy who wore clogs and blond hair down to here—a one-man-band type of musician who played all these things at the same time and sang—who came along this night when Edie and I were hanging out, both tripping our brains out on acid, and he said, “Edie, why don’t you come away with me and 111 straighten you out.” She said, “Okay,” and they were gone. Shit, I was really bugged. I couldn’t argue. The guy was about three times my size. Not that he would have fought me. But I was so stoned I couldn’t even talk. Too much of that sunshine and you can’t say anything.

We’d party in people’s apartments—square and white and ugly, mattresses on the floor, lots of loud music, Led Zeppelin, things like that, and Edie right in the middle of it and loving every minute. Everyone getting loud and freaky and loose. Yet Edie was different. She could be kind of polished and cultured when she wanted to be—we heard she was born with millions.

JONATHAN SEDGWICK

I came in on her once when she was in a typical Isla Vista apartment—two sliding doors, no furniture because it must’ve been wrecked, a bed on the floor, with Edie lying on it, retching. Around her were all these nice groveling drug addicts trying to help her . . . it was sort of like a Hieronymus Bosch feeling.

Only once did I help Edie through an overdose of speed. She was vibrating so much I started shaking like a thousand tons of coffee in

me. Finally I said, “Edie, I just don’t have the power to stop what’s inside you right now.”

Finally she got into this trip of deciding she had to be stopped; since she couldn’t stop herself and her drug-freak friends couldn’t either, she decided she was going to be busted by the cops. I talked with her and said, “Hey, you don’t want to do it that way, man. it’s going to be a bummer for everybody.” She said, “No, I’m going to do it.”

About a week later people came running up. “Hey, did you hear what happened to Edie? She got busted. Edie got busted, man I”

How? Well, this is the way three people told me, so I believe it. While she was walking along the street, she dropped her purse and a whole bunch of reds and things fell out, right? A cop car pulled up. “What ya doing?” And then the cops get the idea that she was carrying drugs on her. So they got out and threw her up against the car, her hands up over the hood, at which point her purse spilled open again and there’re whites, there’re reds falling everywhere I The cop who had pushed her against the car turned around and began picking up the stuff, so she wheeled around and gave him a kick in the ass, man, with all the energy and hate she could, and that sent him flying over the hood of the car. She said, “You fucker, man! Don’t you touch my purse!” Everybody standing along the street was blown out when they saw that. They cheered and clapped. Edie smiled. The cops were really uptight. They grabbed Edie. The cop who’d been kicked was really hurting. Oh, she just blew out a lot of people. She had a lot of energy, man. She only weighed about eighty pounds and he weighed about two hundred pounds, that cop.

It may not have been like that, but that’s what I heard.

HENRY PETERS

The court put Edie on probation for five years. After the drug bust she became a patient at the Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara. It was ironic in a way. She was born there. Her father died there. Now she was twenty-six—it was August 1969—and she had been placed in the Cottage Hospital on her psychiatrist, Dr. Mercer’s, recommendation. She had privileges of sorts—which meant that occasionally she could leave when she wanted to.

EILEEN BENSON

Edie was happy in the hospital, but she wanted to get out every day. I was doing social work in Isla Vista and would come and pick her up. She was usually careful about getting back on time—which was ten p.m. in the psychiatric ward. She loved to eat oysters. Once a week we’d go down to the Reindeer Room in Santa Barbara. She’d survive on chocolate milk and candy bars, especially if she’d been speeding. Visitors brought her drugs and she used to save her sleeping pills so she had extra.

She was good company. She told me about a lot of her troubles. She was very frank. I found her easy to be with. She’d get dressed up and wear her wigs. She had wigs hidden about the ward. She spent her week’s allowance of eighty dollars on padded bras—twenty of them, black and white, that she’d bought at Robinson’s. She hid them because she thought someone might steal them. She told me she was a kleptomaniac

and she’d show me things she’d stolen from the hospital gift shop—little pieces of jewelry, planters without plants, cigarette lighters, little figurines.

HENRY PETERS

she’d sometimes talk about the past. Warhol! She was trying to get him out of her system. She hated the Factory because of the dope. “I hate them. I hate them!” She said he got people screwed up until they were automatons, robots, doing what he wanted them to do, and discarded diem. she said: The

way

those sons-of-bitches took advantage of me. Warhol is a sadistic faggot.” Big black boots and a motorcycle jacket and a whip . . . which is what she said he was like.

PETER DWORKIN

Everybody in Cottage had a kind of ambivalence about Edie . . . an angel in a lot of ways, and it was difficult not to love her. When you come upon an extraordinary person, you allow them a lot more latitude than you do an ordinary person. Edie was very elusive . . . trying hard not to let anybody ever get close to her in any real sense; she would throw up these giant clouds of camouflage. I don’t think she knew that people realized what she was doing. She would have been devastated if she knew people weren’t falling for it. it was poignant to see that people loved Edie for being edie but that she couldn’t accept that: she always had to feed diem something else—that she was “Edie the Model,” “Edie the Movie Star.”

She had a looseleaf notebook with photographs of herself . . . newspaper dippings and cut-outs, mostly from fashion magazines. I remember being saddened by that. She’d show it to the patients so that they could be made sure that she’d been a model and been in movies, and that she was

Edie Sedgwick.

She talked about that stupid horse sculpture that the state bought from her father and then gave to the Earl Warren Showgrounds. She was putting him down but at the same time letting people know that she was somebody.

She insisted on being die center of attention. She’d make noise if people weren’t paving attention to her: she’d shriek and laugh and joke and do outrageous things like eat seven meals at one sitting. She would eat all the food of die patients who weren’t there. It was almost a ward joke: “Edie’s eating!” She’d really shovel the food in. It was frightening because there seemed to be so much anger involved—just forcing this food down herself.

I was very fat then. I weighed about three hundred pounds. I was very unhappy and felt very unattractive. Edie, of course, was exactly the opposite. She made jokes about how skinny she was—that she was a concentration-camp victim. I used to give her back rubs sometimes—in her room or mine. I remember being really fascinated by her body—she didn’t have any breasts, and it was strange to look at her. We had a sexual experience, but it was minimal. It was not such a big deal. We just kind of goofed around. It was exploratory on a lot of different levels. We were caught at it. Somebody walked in and out, and then we put on clothes. It was talked about: “Why don’t you

not

do that . . “

Edie, 1969

MICHAEL POST

I’d just gotten in. The first day. The nurse said, This is your room and this is your roommate, blah, blah, blah.” It was about ten-thirty in the morning. I lay down on the bed, put my hands behind my head, and was just about to take a deep breath and go

Ahhhh,

when Edie came in. She was wearing one of those white cloth things that they make you wear for X-rays. She came in smoking a cigarette—this horrible, raspy cough—and she looked as light as a feather . . . like she was walking on air . . . and she sort of came down and lighted on one side of the bed. She held my wrist. I thought, “Oh, wow, this chick really looks like she’s been through the war! The

war.”

She said, “I’m Edie Sedgwick.” “My goodness,” I thought, “this sure is a friendly hospital.” I said I’d read something about her in the paper not too long before . . . about her father being a sculptor. We went on like that . . . just kind of small talk, really. Down the hall she was in a private room, alone. She walked me down there. Two beds. She had so much junk strewn over the other bed—shoeboxes full of photographs, letters, stuffed animals, drawings, cosmetics, clothing, cigarettes, comic books. ZAP comic books. Have you ever read ZAP comic books? Oh, God! And

Mr. Natural.

That’s how I met her. There wasn’t anything sexual between us while I was in the hospital. I didn’t want to be another statistic on the boards. I saw her go through a number of guys. I totally divorced myself from any sort of sexual association with her because I thought it was a total drunken rip-off. Like once a guy named Preacher came in—filthy jeans, black leather jacket, Hell’s Angels-type guy—and I thought, “What is she doing with

him?”

Before that, it was somebody who’d just gotten out of prison—notorious as the Santa Barbara cat burglar. He would steal people blind while they were right in bed sleeping . . . take the rings and watches off their fingers. He was with her. I didn’t want that. Besides, I had made a vow to myself that

I would not make love to anyone before I was twenty-one. But I thought Edie was fascinating.

I was in Cottage Hospital to quit the drug world. To get away from it. But even in the hospital I couldn’t. People in the corridors kept coming at me to ask, “Can you get me this? Can you get me that?” I would say, “But I’m a patient here. How in the world am I going to get that?” They wanted me to get, like, hundreds of thousands of pills. I’d tell them: “That sort of thing put me in here, and I’m here to come down from it as slowly as possible so that it won’t rip my brains apart. I don’t want to have anything to do with it any more.”