Emotional Design (12 page)

Authors: Donald A. Norman

The world of software is to be commended for its power and chameleon-like ability to transform itself into whatever function is needed. The computer provides for abstract actions. Computer scientists call these environments “virtual worlds,” and although they have many benefits, they eliminate one of the great delights of real interactions: the delight that comes from touching, feeling, and moving real physical objects.

The virtual worlds of software are worlds of cognition: ideas and concepts presented without physical substance. Physical objects involve the world of emotion, where you experience things, whether the comfortable sensuousness of some surfaces or the grating, uncomfortable feel of others. Although software and computers have become indispensable to daily life, too much adherence to the abstraction of the computer screen subtracts from emotional pleasure. Fortunately, some designers of many computer-based products are restoring the natural, affective pleasures of the real, tangible world. Physical controls are back in style: knobs for tuning, knobs for volume, levers for turning or switching. Hurrah!

Badly conceived behavioral design can lead to great frustration, leading to objects that have lives of their own, that refuse to obey, that provide inadequate feedback about their actions, that are unintelligible, and all in all, putting anyone who tries to use them into a big, gray funk. No wonder this frustration often erupts in rage, causes the user to kick, scream, and curse. Worse, there is no excuse for such frustration. The fault does not lie with the user; the fault lies with the design.

Why do so many designs fail? Mainly because designers and engineers are often self-centered. Engineers tend to focus upon technology,

putting into a product whatever special features they themselves prefer. Many designers fail as well through their fondness for the sophisticated use of images, metaphors, and semantics that win prizes in design competitions but create products that are inaccessible to users. Web sites fail here as well, for the creators focus either upon the technical sophistication of images and sounds, or upon making sure that each division of a company receives the recognition that its political power dictates.

putting into a product whatever special features they themselves prefer. Many designers fail as well through their fondness for the sophisticated use of images, metaphors, and semantics that win prizes in design competitions but create products that are inaccessible to users. Web sites fail here as well, for the creators focus either upon the technical sophistication of images and sounds, or upon making sure that each division of a company receives the recognition that its political power dictates.

None of these cases takes into account the concerns of the poor user, people like you and me, who use a product or web site to satisfy some need. You need to accomplish a task or to find some information. You don't know the organizational chart of the company on whose web site you seek information, nor do you wish to. You may enjoy flashy images and sounds briefly, but not when that cleverness and sophistication get in the way of getting your job done.

Good behavioral design should be human-centered, focusing upon understanding and satisfying the needs of the people who actually use the product. As I have said, the best way to discover these needs is through observation, when the product is being used naturally, and not in response to some arbitrary request to “show us how you would do x.” But observation is surprisingly rare. You would think that manufacturers would want to watch people use their products, the better to improve them for the future. But no, they are too busy designing and matching the features of the competition to find out whether their products are really effective and usable.

Engineers and designers explain that, being people themselves, they understand people, but this argument is flawed. Engineers and designers simultaneously know too much and too little. They know too much about the technology and too little about how other people live their lives and do their activities. In addition, anyone involved with a product is so close to the technical details, to the design difficulties, and to the project issues that they are unable to view the product the way an unattached person can.

Focus groups, questionnaires, and surveys are poor tools for learning

about behavior, for they are divorced from actual use. Most behavior is subconscious and what people actually do can be quite different from what they think they do. We humans like to think that we know why we act as we do, but we don't, however much we like to explain our actions. The fact that both visceral and behavioral reactions are subconscious makes us unaware of our true reactions and their causes. This is why trained professionals who observe real use in real situations can often tell more about people's likes and dislikesâand the reasons for themâthan the people themselves.

about behavior, for they are divorced from actual use. Most behavior is subconscious and what people actually do can be quite different from what they think they do. We humans like to think that we know why we act as we do, but we don't, however much we like to explain our actions. The fact that both visceral and behavioral reactions are subconscious makes us unaware of our true reactions and their causes. This is why trained professionals who observe real use in real situations can often tell more about people's likes and dislikesâand the reasons for themâthan the people themselves.

An interesting exception to these problems comes when designers or engineers are building something for themselves that they will use frequently in their own everyday lives. Such products tend to excel. As a result, the best products today, from a behavioral point of view, are often those that come from the athletic, sports, and craft industries, because these products do get designed, purchased, and used by people who put behavior above everything else. Go to a good hardware store and examine the hand tools used by gardeners, woodworkers, and machinists. These tools, developed over centuries of use, are carefully designed to feel good, to be balanced, to give precise feedback, and to perform well. Go to a good outfitter's shop and look at a mountain climber's tools or at the tents and backpacks used by serious hikers and campers. Or go to a professional chef's supply house and examine what real chefs buy and use in their kitchens.

I have found it interesting to compare the electronic equipment sold for consumers with the equipment sold to professionals. Although much more expensive, the professional equipment tends to be simpler and easier to use. Video recorders for the home market have numerous flashing lights, many buttons and settings, and complex menus for setting the time and programming future recording. The recorders for the professionals just have the essentials and are therefore easier to use while functioning better. This difference arises, in part, because the designers will be using the products themselves, so they know just what is important and what is not. Tools made by artisans for themselves all have this property. Designers of hiking or mountain climbing

equipment may one day find their lives depending upon the quality and behavior of their own designs.

equipment may one day find their lives depending upon the quality and behavior of their own designs.

When the company Hewlett Packard was founded, their main product was test equipment for electrical engineers. “Design for the person on the next bench,” was the company motto, and it served them well. Engineers found that HP products were a joy to use because they fitted the task of the electrical engineer at the design or test bench perfectly. But today, the same design philosophy no longer works: the equipment is often used by technicians and field crew who have little or no technical background. The “next bench” philosophy that worked when the designers were also users fails when the populations change.

Good behavioral design has to be a fundamental part of the design process from the very start; it cannot be adopted once the product has been completed. Behavioral design begins with understanding the user's needs, ideally derived by conducting studies of relevant behavior in homes, schools, places of work, or wherever the product will actually be used. Then the design team produces quick, rapid prototypes to test on prospective users, prototypes that take hours (not days) to build and then to test. Even simple sketches or mockups from cardboard, wood, or foam work well at this stage. As the design process continues, it incorporates the information from the tests. Soon the prototypes are more complete, sometimes fully or partially working, sometimes simply simulating working devices. By the time the product is finished, it has been thoroughly vetted through usage: final testing is necessary only to catch minor mistakes in implementation. This iterative design process is the heart of effective, user-centered design.

Reflective DesignReflective design covers a lot of territory. It is all about message, about culture, and about the meaning of a product or its use. For one,

it is about the meaning of things, the personal remembrances something evokes. For another, very different thing, it is about self-image and the message a product sends to others. Whenever you notice that the color of someone's socks matches the rest of his or her clothes or whether those clothes are right for the occasion, you are concerned with reflective self-image.

it is about the meaning of things, the personal remembrances something evokes. For another, very different thing, it is about self-image and the message a product sends to others. Whenever you notice that the color of someone's socks matches the rest of his or her clothes or whether those clothes are right for the occasion, you are concerned with reflective self-image.

FIGURE 3.6

Reflective design through cleverness.

Reflective design through cleverness.

The value of this watch comes from the clever representation of time: Quick, what time is represented? This is

Time by Design's

“ Pie ” watch showing the time of 4:22 and 37 seconds. The goal of the company is to invent new ways of telling time, combiing “art and time telling into amusing and thought provoking clocks and watches.” This watch is as much a statement about the wearer as it is a timepiece.

Time by Design's

“ Pie ” watch showing the time of 4:22 and 37 seconds. The goal of the company is to invent new ways of telling time, combiing “art and time telling into amusing and thought provoking clocks and watches.” This watch is as much a statement about the wearer as it is a timepiece.

(Courtesy of Time by Design.)

Whether we wish to admit it or not, all of us worry about the image we present to othersâor, for that matter, about the self-image that we present to ourselves. Do you sometimes avoid a purchase “because it wouldn't be right” or buy something in order to support a cause you prefer? These are reflective decisions. In fact, even people who claim a complete lack of interest in how they are perceivedâdressing in whatever is easiest or most comfortable, refraining from purchasing new items until the ones they are using completely stop workingâmake statements about themselves and the things they care about. These are all properties of reflective processing.

Consider two watches. The first one, by “Time by Design” (

figure 3.6

), exhibits reflective delight in using an unusual means to display time, one that has to be explained to be understood. The watch is also viscerally attractive, but the main appeal is its unusual display. Is the time more difficult to read than on a traditional analog or digital

watch? Yes, but it has an excellent underlying conceptual model, satisfying one of my maxims of good behavioral design: it need only be explained once; from then on, it is obvious. Is it awkward to set the watch because it has but a single control? Yes, but the reflective delight in showing off the watch and explaining its operation outweighs the difficulties. I own one myself and, as my weary friends will attest, proudly explain it to anyone who shows the slightest bit of interest. The reflective value outweighs the behavioral difficulties.

figure 3.6

), exhibits reflective delight in using an unusual means to display time, one that has to be explained to be understood. The watch is also viscerally attractive, but the main appeal is its unusual display. Is the time more difficult to read than on a traditional analog or digital

watch? Yes, but it has an excellent underlying conceptual model, satisfying one of my maxims of good behavioral design: it need only be explained once; from then on, it is obvious. Is it awkward to set the watch because it has but a single control? Yes, but the reflective delight in showing off the watch and explaining its operation outweighs the difficulties. I own one myself and, as my weary friends will attest, proudly explain it to anyone who shows the slightest bit of interest. The reflective value outweighs the behavioral difficulties.

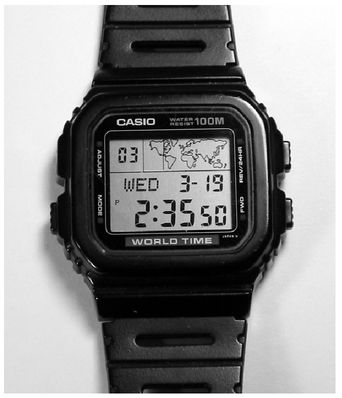

FIGURE 3.7

Pure behavioral design.

Pure behavioral design.

The

Casio

“G-Shock” watch is pure behavioral design; efficient and effective, with no claims to beauty and low in such measures of reflective design as prestige and status. But consider the behavioral aspects: two time zones, a stopwatch, a countdown timer, and an alarm. Inexpensive, easy to use, and accurate.

Casio

“G-Shock” watch is pure behavioral design; efficient and effective, with no claims to beauty and low in such measures of reflective design as prestige and status. But consider the behavioral aspects: two time zones, a stopwatch, a countdown timer, and an alarm. Inexpensive, easy to use, and accurate.

(Author's collection.)

Now contrast this reflective design with the practical, sensible, plastic digital watch by Casio (

figure 3.7

). This is a practical watch, one emphasizing the behavioral level of design without any attributes of visceral or reflective design. This is an engineer's watch: practical, straightforward, multiple features, and low price. It isn't particularly attractiveâthat isn't its selling point. Moreover, the watch has no special reflective appeal, except perhaps through the reverse logic of being proud to own such a utilitarian watch when one can afford a much more expensive one. (For the record, I own both these watches, wearing the Time by Design one for formal affairs, the Casio otherwise.)

figure 3.7

). This is a practical watch, one emphasizing the behavioral level of design without any attributes of visceral or reflective design. This is an engineer's watch: practical, straightforward, multiple features, and low price. It isn't particularly attractiveâthat isn't its selling point. Moreover, the watch has no special reflective appeal, except perhaps through the reverse logic of being proud to own such a utilitarian watch when one can afford a much more expensive one. (For the record, I own both these watches, wearing the Time by Design one for formal affairs, the Casio otherwise.)

A number of years ago I visited Biel, Switzerland. I was part of a small product team for an American high-technology company, there

to talk with the folks at Swatch, the watch company that had transformed the Swiss watchmaking industry. Swatch, we were proudly told, was not a watch company; it was an emotions company. Sure, they made the precision watches and movements used in most watches around the world (regardless of the brand displayed on the case), but what they had really done was to transform the purpose of a watch from timekeeping to emotion. Their expertise, their president boldly proclaimed, was human emotion, as he rolled up his sleeves to display the many watches on his arm.

to talk with the folks at Swatch, the watch company that had transformed the Swiss watchmaking industry. Swatch, we were proudly told, was not a watch company; it was an emotions company. Sure, they made the precision watches and movements used in most watches around the world (regardless of the brand displayed on the case), but what they had really done was to transform the purpose of a watch from timekeeping to emotion. Their expertise, their president boldly proclaimed, was human emotion, as he rolled up his sleeves to display the many watches on his arm.

Other books

Classified Woman by Sibel Edmonds

The Cowboy’s Runaway Bride (BBW Romance - Billionaire Brothers 1) by Roseton, Jenn

Break Me Open by Amy Kiss

Silent Night by Rowena Sudbury

Interest by Kevin Gaughen

A Pirate's Heart (St. John Series) by Lora Thomas

Jacob's Ladder by Donald Mccaig

The Inconvenient Bride by J. A. Fraser

The Vampire and the Virgin by Kerrelyn Sparks

Rise Again by Ben Tripp