Enemy on the Euphrates (27 page)

Read Enemy on the Euphrates Online

Authors: Ian Rutledge

Long live Independence.

Liberty is the daughter of Independence.

No Liberty without Independence and no Honour without Liberty.

We want Independence and we will not have independence except

under the shade of the Arab Flag and with the Arab Union.

The Life of the Arabs is in the Union.

Demand your Independence until death.

25

Although many of the barely literate citizens of Baghdad could not themselves read the leaflets, their very existence attracted great curiosity. Therefore they were usually taken to one of the hundreds of coffee shops around the city, where someone who could read was called upon to make a public recitation of the subversive patriotic or religious slogans.

In addition to this literature of resistance and rebellion emanating from the nationalists at the Ahliyya school, two additional currents of anti-British propaganda began to swirl around the city. The first of these represented the views of a sizeable body of men who believed that the Iraqi resistance should establish close links with Mustafa Kemal’s growing nationalist movement in Anatolia with a view to creating a new, reformed pan-Islamic state. With British, French, Italian and Greek troops occupying large areas of Turkey including the capital Istanbul, between 4 and 11 September 1919, Mustafa Kemal and his allies held a momentous conference at Sivas in south-east Anatolia, where they pledged to free their country from foreign occupation. Among those attending were a number of anti-British Arab notables including the redoubtable paramount chief of the Muntafiq, ‘Ajaimi Sa‘dun, who had commanded part of the mujahidin at the battle of Shu’ayba and now led a small army of Arab horsemen in the no-man’s-land of north-west Iraq.

Ja‘far Abu al-Timman, one of the principal nationalists in Baghdad,

c.

1920

Any lingering hostility between Turks and Arabs which had developed during the war had, by now, considerably diminished as the two nationalities and co-religionists recognised they once again had a powerful common enemy. In Baghdad the pro-Turkish faction held a number of meetings in May attended mainly by former Ottoman military and police officers, and other former Ottoman government officials. They formally rejected the British mandate and demanded either a Turkish mandate or complete independence and proposed the establishment of a political organisation, Fida’ al-Watan (Self-sacrifice for the Homeland), to campaign for these objectives.

However, the pro-Turkish resistance faction in Baghdad faced a number of difficulties. Firstly, the Kemalists had already renounced all claims to former Ottoman territories containing Arab majorities, although the Kurds were specifically claimed as Turks. Since the province of Mosul with a large Kurdish population was therefore designated as ‘Turkish’, the Kemalists laid claimed to sovereignty over it. This presented a serious difficulty for the pro-Turkish resistance faction and a point of friction with the other resistance groups (and indeed, popular sentiment throughout the other two provinces, Baghdad and Basra). Both al-‘Ahd and Haras al-Istiqlal wanted Mosul to remain within a unified Iraq. Secondly, hundreds of miles to the north, in Anatolia, the Kemalists were themselves desperately embattled: even if they had wished to provide military support for an anti-British uprising in Iraq, or in Mosul alone, they simply did not have the resources. Indeed, by early 1920 they were urgently seeking (and receiving) arms from the Bolsheviks, who by now were successfully counter-attacking the White Russian armies and their British, French, American and Japanese interventionist supporters.

It was Bolshevik support for the Turkish nationalists, together with news from Persia of Bolshevik advances in the north in alliance with Persian nationalists, that led to a growing curiosity among some of the younger Iraqi nationalists – not only in Baghdad but also within the Shi‘i holy cities – about

balshafiyya

(Bolshevism), this strange new political phenomenon which appeared to be successfully challenging European imperialism throughout the region.

By mid-1919 the Bolsheviks had already established an organisation called Jam‘iyya al-Takhlis al-Sharq al-Islami (Organisation for the Liberation of the Muslim East) under the aegis of the Eastern Department of Narkomindel (Peoples’ Commissariat for Foreign Affairs) with the object of supporting and encouraging the struggle of the Muslim peoples against European domination.

26

The Jam‘iyya had a secret base in Anatolia, protected by the forces of Mustafa Kemal and charged with spreading anti-British subversion, a task made considerably easier by the now widely known details of the infamous Sykes–Picot Agreement that the Bolsheviks had published.

By January 1920 the British police in Baghdad were beginning to receive reports of ‘Bolshevik talk’ in the coffee shops and mosques of Baghdad, and of the circulation of a pamphlet entitled

Bolshevism and Islam

, written by an Indian Muslim with strong Bolshevik leanings called Muhammad Barkatullah. His pamphlet was a curious and discordant mixture of pro-Communist, Pan-Islamist, and pro-Young Turk propaganda whose principal objective was to create sympathy among the Muslim peoples for the Bolshevik revolution. Beginning with an uncompromising declaration of praise for the Young Turk revolution of 1908, it went on to blame the Western Powers for ‘extinguishing’ it through war, exalting the CUP government for its resistance and denouncing the Sharif of Mecca for treachery. ‘Today’, the pamphlet stated, ‘not a single Muslim state remains independent’. However, ‘There is no cause for despair! Following on the long dark nights of Tsarist autocracy, the dawn of human freedom has appeared on the Russian horizon, with Lenin as the shining sun giving light and splendour this day of human happiness.’

27

Whatever the Muslims of Baghdad made of this remarkable declaration – and as we shall see, there is a evidence to show that at least some among the educated

were

favourably impressed – the British were already becoming near-hysterical about what they saw as a vast Bolshevik–Kemalist threat to their interests in the Middle East. Not only was there a growing fear of Bolshevik agents infiltrating from Persia, but the presence of Bolshevik-armed Turkish nationalist forces in eastern and southern Anatolia, only a few hundred miles north of Mosul, was giving rise to the wildest imaginings of the British authorities in Iraq, such as a report of the presence of a mysterious ‘Colonel Koloff’ at Kemalist-controlled Diyarbakir, supposedly ‘a prominent personage’ in something called ‘the Bolshevist Green Army’.

28

Similarly, in the words of the Baghdad magistrate Thomas Lyell, Mustafa Kemal had ‘joined the Bolshevik Headquarters in Asia Minor’ and ‘it is well known … that no small proportion of the Red Army of Bolshevik Russia is Muslim.’

29

Likewise, for Gertrude Bell, there was ‘no lack of evidence to show that a league of conspiracy, organised by the Bolsheviks in cooperation with the Turkish Nationalists (has) long been in touch with extremist Arab political societies’.

30

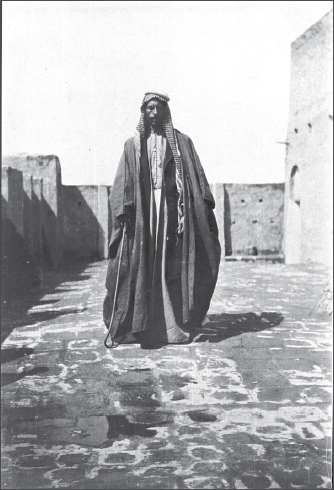

Sheikh ‘Abd al-Wahid al-Sikar of the Fatla Tribe, 1918. One of the principal Arab tribal leaders during the uprising.

Perhaps surprisingly, the one source of political influence in Baghdad which appears to have been fading at this time was that of al-‘Ahd. Although the party had a branch in Baghdad including civilian members, the organisation had always been stronger in Mosul, partly because of its closer proximity to the al-‘Ahd HQ in Damascus.

31

Moreover, the official line of the Baghdad branch of the party that an independent Iraq would seek ‘technical assistance’ from the British – a position which was strongly opposed by Haras al-Istiqlal – seemed increasingly out of tune with popular sentiment whose antipathy towards the British occupation was approaching the point of explosion.

32

In an attempt to heal the rift between al-‘Ahd and the Istiqlal, the Damascus headquarters of al-‘Ahd sent two leading Iraqi members, Jamil al-Midfa‘i and Ibrahim Kamal, to Baghdad, where, for a time, they managed to bring the two organisations into a common front,

33

but not long after they had returned to Syria, the schism re-emerged.

Although Haras al-Istiqlal was essentially a Baghdad-based organisation, by the spring of 1920 it had established branches in nearby Kadhimayn and in some important localities in the mid-Euphrates – Najaf, Hilla and Shamiyya. On 22 April two emissaries from this region arrived in Baghdad. They were Hadi al-Zwayn, a prominent sayyid from the mid-Euphrates town of Hilla, and ‘Abd al-Muhsin Shilash, a leading Najafi merchant with widespread dealings among the Euphrates tribes. Abu al-Timman swiftly convened a gathering of Istiqlal followers and sympathisers including Muhammad al-Sadr, Yusuf Suwaydi and other prominent members of the organisation. As the two messengers related their news the Baghdad nationalists must have listened with growing excitement. The emissaries’ report was startling. Only the previous day, most of the leading sheikhs and sada had met with the Grand Mujtahid Taqi al-Shirazi in Karbela’ and agreed to take an oath on the Qur’an at the mosques of Husayn and ‘Abbas committing them to rejecting British authority.

34

They were ready to take up arms against the occupation provided the religious leadership in Najaf and Karbela’ gave the word. Moreover, although the emissaries’ bitter complaints against the British – excessive taxation, forced labour, a particularly brutal PO in one division – Diwaniyya – were primarily local grievances, they were now becoming articulated in the language of ‘national independence’.

At the close of the meeting at Abu al-Timman’s home it was decided that Ja‘far himself should be sent to Karbela’ to observe and evaluate the extent of the tribal mobilisation in the surrounding region and establish a permanent link between the Baghdad nationalists and the Shi‘i holy places.

35

So on 4 May 1920, in the golden-domed city of Karbela’, Abu al-Timman was ushered into a secret congregation of sheikhs and sada in the presence of the Grand Mujtahid Mirza Muhammad Taqi al-Shirazi and his son Mirza Muhammad Ridha.

36

The meeting was held in the Dar al-Hujja (House of Religious Debate) in Karbela’. Shirazi, a diminutive figure in a large white turban, was seated on a low couch supported by pillows and by his side sat Mirza Muhammad Ridha, himself already grey-bearded, wearing a smaller white turban. By now Ridha was the

intellectual driving force behind the independence movement in the mid-Euphrates. He was president of al-Jam‘iyya al-‘Iraqiyya al-‘Arabiyya which advocated collaboration with both the Kemalists and the Bolsheviks and he believed that some, at least, of the political principles of the latter were compatible with the values of Shi‘i Islam.

37

In fact, he had already been accused by the British of openly disseminating the contents of an Arabic book entitled

Mabadi’ al-Balshafiyya

(The Principles of Bolshevism). According to British police reports, Ridha was actually ‘in touch with the Bolsheviks, who, in an open telegram, proclaimed him to be the head of the movement of liberation from the British’, and he was ‘mentioned by name in a wireless message issued by the Bolsheviks at Resht [in Persia] as working for the Bolshevik cause at Karbela’.

38

Along each side of the Dar al-Hujja sat the invited mujtahidin, sheikhs and sada, carefully seated on their own low couches with their feet tucked under them; among them ‘Abd al-Wahid Sikar, sheikh of the al-Fatla tribe, a thin-faced man with high cheekbones, moustached but beardless, wearing a black cloak and the white kufiyya with black mesh patterning typical of the Shi‘is; present also was Sha’lan Abu al-Jun, sheikh of the Dhawalim section of the Bani Huchaym, an older, burly man, black bearded but similarly attired. The contingent of green-turbaned tribal sada, their black cloaks draped over their shoulders in the customary manner, included Sayyid Hadi al-Zwayn, one of the two emissaries to Baghdad, and Sayyid Nur al-Sayyid ‘Aziz, both men of high status in a society which accepted and greatly valued their claim of descent from the line of Husayn and the Prophet.

39