Epic Historial Collection (127 page)

Read Epic Historial Collection Online

Authors: Ken Follett

“I've missed this,” Jack said in her ear, and his voice was hoarse with lust and some other emotion, sadness perhaps.

Aliena's throat was dry with desire. She said: “Are we going to break our promise?”

“Now, and forevermore.”

“What do you mean?”

“We're not going to live apart. We're leaving Kingsbridge.”

“But what will you do?”

“Go to a different town and build another cathedral.”

“But you won't be master. It won't be your design.”

“One day I may get another chance. I'm young.”

It was possible, but the odds were against it, Aliena knew; and Jack knew it too. The sacrifice he was making for her moved her to tears. Nobody had ever loved her like this; nobody else ever would. But she was not willing to let him give up everything. “I won't do it,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“I'm not going to leave Kingsbridge.”

He was angry. “Why not? Anywhere else, we can live as man and wife, and nobody will care. We could even get married in a church.”

She touched his face. “I love you too much to take you away from Kingsbridge Cathedral.”

“That's for me to decide.”

“Jack, I love you for offering. The fact that you're ready to give up your life's work to live with me isâ¦it almost breaks my heart that you should love me so much. But I don't want to be the woman who took you away from the work you loved. I'm not willing to go with you that way. It will cast a shadow over our entire lives. You may forgive me for it, but I never will.”

Jack looked sad. “I know better than to fight you once you've decided. But what will we do?”

“We'll try again for the annulment. We'll live apart.”

He looked miserable.

She finished: “And we'll come here every Sunday and break our promise.”

He pressed up against her, and she could feel him becoming aroused again. “Every Sunday?”

“Yes.”

“You might get pregnant again.”

“We'll take that chance. And I'm going to start manufacturing cloth, as I used to. I've bought Philip's unsold wool again, and I'm going to organize the townspeople to spin and weave it. Then I'll felt it in the fulling mill.”

“How did you pay Philip?” Jack said in surprise.

“I haven't, yet. I'm going to pay him in bales of cloth, when it's made.”

Jack nodded. He said bitterly: “He agreed to that because he wants you to stay here so that I'll stay.”

Aliena nodded. “But he'll still get cheap cloth out of it.”

“Damn Philip. He always gets what he wants.”

Aliena saw that she had won. She kissed him and said: “I love you.”

He kissed her back, running his hands all over her body, greedily feeling her secret places. Then he stopped and said: “But I want to be with you every night, not just on Sundays.”

She kissed his ear. “One day we will,” she breathed. “I promise you.”

He moved behind her, drifting in the water, and pulled her to him, so that his legs were underneath her. She parted her thighs and floated down gently into his lap. He stroked her full breasts with his hands and played with her swollen nipples. Finally he penetrated her, and she shuddered with pleasure.

They made love slowly and gently in the cool pond, with the rush of the waterfall in their ears. Jack put his arms around her bump, and his knowing hands touched her between her legs, pressing and stroking as he went in and out. They had never done this before, made love this way, so that he could caress her most sensitive places at the same time, and it was sharply different, a more intense pleasure, different the way a stabbing pain is different from a dull ache; but perhaps that was because she felt so sad. After a while she abandoned herself to the sensation. Its intensity built up so quickly that the climax took her by surprise, almost frightening her, and she was racked by spasms of pleasure so convulsive that she screamed.

He stayed inside her, hard, unsatisfied, while she caught her breath. He was still, no longer thrusting, but she realized he had not reached a climax. After a while she began to move again, encouragingly, but he did not respond. She turned her head and kissed him over her shoulder. The water on his face was warm. He was weeping.

1152-1155

A

FTER SEVEN YEARS

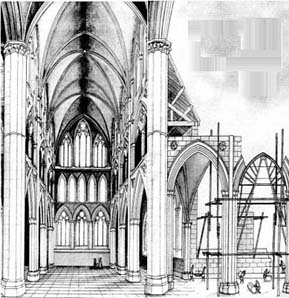

Jack had finished the transeptsâthe two arms of the cross-shaped churchâand they were everything he had hoped for. He had improved on the ideas of Saint-Denis, making everything taller and narrowerâwindows, arches, and the vault itself. The clustered shafts of the piers rose gracefully through the gallery and became the ribs of the vault, curving over to meet in the middle of the ceiling, and the tall pointed windows flooded the interior with light. The moldings were fine and delicate, and the carved decoration was a riot of stone foliage.

And there were cracks in the clerestory.

He stood in the high clerestory passage, staring out across the chasm of the north transept, brooding on a bright spring morning. He was shocked and baffled. By all the wisdom of the masons the structure was strong; but a crack showed a weakness. His vault was higher than any other he had ever seen, but not by that much. He had not made the mistake of Alfred, and put a stone vault on a structure that was not built to take the weight: his walls had been designed for a stone vault. Yet cracks had appeared in his clerestory in roughly the same place where Alfred's had failed. Alfred had miscalculated but Jack was sure he had not done the same thing. Some new factor was operating in Jack's building and he did not know what it was.

It was not dangerous, not in the short term. The cracks had been filled with mortar and they had not yet reappeared. The building was safe. But it was weak; and for Jack the weakness spoiled it. He wanted his church to last until the Day of Judgment.

He left the clerestory and went down the turret staircase to the gallery, where he had made his tracing floor, in the corner where there was a good light from one of the windows in the north porch. He began to draw the plinth of a nave pier. He drew a diamond, then a square inside the diamond, then a circle inside the square. The main shafts of the pier would spring from the four points of the diamond and rise up the column, eventually branching off north, south, east and west to become arches or ribs. Subsidiary shafts, springing from the corners of the square, would rise to become vaulting ribs, going diagonally across the nave vault on one side and the aisle vault on the other. The circle in the middle represented the core of the pier.

All Jack's designs were based on simple geometrical shapes and some not-so-simple proportions, such as the ratio of the square root of two to the square root of three. Jack had learned how to figure square roots in Toledo, but most masons could not calculate them, and instead used simple geometric constructions. They knew that if a circle was drawn around the four corners of a square, the diameter of the circle was bigger than the side of the square in the ratio of the square root of two to one. That ratio, root-two to one, was the most ancient of the masons' formulas, for in a simple building it was the ratio of the outside width to the inside width, and therefore gave the thickness of the wall.

Jack's task was much complicated by the religious significance of various numbers. Prior Philip was planning to rededicate the church to the Virgin Mary, because the Weeping Madonna worked more miracles than the tomb of Saint Adophus; and in consequence they wanted Jack to use the numbers nine and seven, which were Mary's numbers. He had designed the nave with nine bays and the new chancel, to be built when all else was finished, with seven. The interlocked blind arcading in the side aisles would have seven arches per bay, and the west facade would have nine lancet windows. Jack had no opinion about the theological significance of numbers but he felt instinctively that if the same numbers were used fairly consistently it was bound to add to the harmony of the finished building.

Before he could finish his drawing of the plinth he was interrupted by the master roofer, who had hit a problem and wanted Jack to solve it.

Jack followed the man up the turret staircase, past the clerestory, and into the roof space. They walked across the rounded domes that were the top side of the ribbed vault. Above them, the roofers were unrolling great sheets of lead and nailing them to the rafters, starting at the bottom and working up so that the upper sheets would overlap the lower and keep the rain out.

Jack saw the problem immediately. He had put a decorative pinnacle at the end of a valley between two sloping roofs, but he had left the design to a master mason, and the mason had not made provision for rainwater from the roof to pass through or under the pinnacle. The mason would have to alter it. He told the master roofer to pass this instruction on to the mason, then he returned to his tracing floor.

He was astonished to find Alfred waiting for him there.

He had not spoken to Alfred for ten years. He had seen him at a distance, now and again, in Shiring or Winchester. Aliena had not so much as caught sight of him for nine years, even though they were still married, according to the Church. Martha went to visit him at his house in Shiring about once a year. She always brought back the same report: he was prospering, building houses for the burgers of Shiring; he lived alone; he was the same as ever.

But Alfred did not appear prosperous now. Jack thought he looked tired and defeated. Alfred had always been big and strong, but now he had a lean look: his face was thinner, and the hand with which he pushed the hair out of his eyes was bony where it had once been beefy.

He said: “Hello, Jack.”

His expression was aggressive but his tone of voice was ingratiatingâan unattractive mixture.

“Hello, Alfred,” Jack said warily. “Last time I saw you, you were wearing a silk tunic and running to fat.”

“That was three years agoâbefore the first of the bad harvests.”

“So it was.” Three bad harvests in a row had caused a famine. Serfs had starved, many tenant farmers were destitute, and presumably the burgers of Shiring could no longer afford splendid new stone houses. Alfred was feeling the pinch. Jack said: “What brings you to Kingsbridge after all this time?”

“I heard about your transepts and came to look.” His tone was one of grudging admiration. “Where did you learn to build like this?”

“Paris,” Jack said shortly. He did not want to discuss that period of his life with Alfred, who had been the cause of his exile.

“Well.” Alfred looked awkward, then said with elaborate indifference: “I'd be willing to work here, just to pick up some of these new tricks.”

Jack was flabbergasted. Did Alfred really have the nerve to ask him for a job? Playing for time, he said: “What about your gang?”

“I'm on my own now,” Alfred said, still trying to be casual. “There wasn't enough work for a gang.”

“We're not hiring, anyway,” Jack said, equally casually. “We've got a full complement.”

“But you can always use a good mason, can't you?”

Jack heard a faint pleading note and realized that Alfred was desperate. He decided to be honest. “After the life we've had, Alfred, I'm the last person you should come to for help.”

“You are the last,” Alfred said candidly. “I've tried everywhere. Nobody's hiring. It's the famine.”

Jack thought of all the times Alfred had mistreated him, tormented him, and beaten him. Alfred had driven him into the monastery and then had driven him away from his home and family. He had no reason to help Alfred: indeed, he had cause to gloat over Alfred's misfortune. He said: “I wouldn't take you on even if I was needing men.”

“I thought you might,” Alfred said with bullheaded persistence. “After all, my father taught you everything you know. It's because of him that you're a master builder. Won't you help me for his sake?”

For Tom. Suddenly Jack felt a twinge of conscience. In his own way, Tom had tried to be a good stepfather. He had not been gentle or understanding, but he had treated his own children much the same as Jack, and he had been patient and generous in passing on his knowledge and skills. He had also made Jack's mother happy, most of the time. And after all, Jack thought, here I am, a successful and prosperous master builder, well on the way to achieving my ambition of building the most beautiful cathedral in the world, and there's Alfred, poor and hungry and out of work. Isn't that revenge enough?

No, it's not, he thought.

Then he relented.

“All right,” he said. “For Tom's sake, you're hired.”

“Thank you,” Alfred said. His expression was unreadable. “Shall I start right away?”

Jack nodded. “We're laying foundations in the nave. Just join in.”

Alfred held out his hand. Jack hesitated momentarily, then shook it. Alfred's grip was as strong as ever.

Alfred disappeared. Jack stood staring down at his drawing of a nave plinth. It was life-size, so that when it was finished a master carpenter could make a wooden template directly from the drawing. The template would then be used by the masons to mark the stones for carving.

Had he made the right decision? He recalled that Alfred's vault had collapsed. However, he would not use Alfred on difficult work such as vaulting or arches: straightforward walls and floors were his metier.

While Jack was still pondering, the noon bell rang for dinner. He put down his sharpened-wire drawing instrument and went down the turret staircase to ground level.

The married masons went home to dinner and the single ones ate in the lodge. On some building sites dinner was provided, as a way of preventing afternoon lateness, absenteeism and drunkenness; but monks' fare was often Spartan and most building workers preferred to provide their own. Jack was living in Tom Builder's old house with Martha, his stepsister, who acted as his housekeeper. Martha also minded Tommy and Jack's second child, a girl whom they had named Sally, while Aliena was busy. Martha usually made dinner for Jack and the children, and Aliena sometimes joined them.

He left the priory close and walked briskly home. On the way a thought struck him. Would Alfred expect to move back into the house with Martha? She was his natural sister, after all. Jack had not thought of that when he gave Alfred the job.

It was a foolish fear, he decided a moment later. The days when Alfred could bully him were long past. He was the master builder of Kingsbridge, and if he said Alfred could not move into the house, then Alfred would not move into the house.

He half expected to find Alfred at the kitchen table, and was relieved to find he was not. Aliena was watching the children eat, while Martha stirred a pot on the fire. The smell of lamb stew was mouth-watering.

He kissed Aliena's forehead briefly. She was thirty-three years old now, but she looked as she had ten years ago: her hair was still a rich dark-brown mass of curls, and she had the same generous mouth and fine, dark eyes. Only when she was naked did she show the physical effects of time and childbirth: her marvelous deep breasts were lower, her hips were broader, and her belly had never reverted to its original taut flatness.

Jack looked affectionately at the two offspring of Aliena's body: nine-year-old Tommy, a healthy red-haired boy, big for his age, shoveling lamb stew into his mouth as if he had not eaten for a week; and Sally, age seven, with dark curls like her mother's, smiling happily and showing a gap between her front teeth just like the one Martha had had when Jack first saw her seventeen years ago. Tommy went to the school in the priory every morning to learn to read and write, but the monks would not take girls, so Aliena was teaching Sally.

Jack sat down, and Martha took the pot off the fire and set it on the table. Martha was a strange girl. She was past twenty years old, but she showed no interest in getting married. She had always been attached to Jack, and now she seemed perfectly content to be his housekeeper.

Jack presided over the oddest household in the county, without a doubt. He and Aliena were two of the leading citizens of the town: he the master builder at the cathedral and she the largest manufacturer of cloth outside Winchester. Everyone treated them as man and wife, yet they were forbidden to spend nights together, and they lived in separate houses, Aliena with her brother and Jack with his stepsister. Every Sunday afternoon, and on every holiday, they would disappear, and everyone knew what they were doing except, of course, Prior Philip. Meanwhile, Jack's mother lived in a cave in the forest because she was supposed to be a witch.

Every now and again Jack got angry about not being allowed to marry Aliena. He would lie awake, listening to Martha snoring in the next room, and think: I'm twenty-eight years oldâwhy am I sleeping alone? The next day he would be bad-tempered with Prior Philip, rejecting all the chapter's suggestions and requests as impracticable or overexpensive, refusing to discuss alternatives or compromises, as if there were only one way to build a cathedral and that was Jack's way. Then Philip would steer clear of him for a few days and let the storm blow over.

Aliena, too, was unhappy, and she took it out on Jack. She would become impatient and intolerant, criticizing everything he did, putting the children to bed as soon as he came in, saying she was not hungry when he ate. After a day or two of this mood she would burst into tears and say she was sorry, and they would be happy again, until the next time the strain became too much for her.

Jack ladled some stew into a bowl and began to eat. “Guess who came to the site this morning,” he said. “Alfred.”