Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (57 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

5.

Ask if the patient knows what investigations have been performed (see investigations below).

6.

Ask about current and past treatment and how helpful this has been. Pituitary surgery and radiotherapy have a number of complications.

7.

As with any chronic illness, the effect of acromegaly on the patient’s life may be severe. Ask about occupation and ability to work.

The examination

FIGURE 10.6

Acromegalic appearance.

Investigations

1.

The preferred test is measurement of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I). Unlike growth hormone (GH) which is affected by exercise and diet, the level of IGF-I does not fluctuate and the absolute level reliably reflects the average GH level. There is physiological elevation of the level in pregnancy and during puberty, but otherwise elevation is very specific for acromegaly. The diagnosis is usually confirmed with a glucose tolerance test, where GH suppression (normal to <0.33μg/L – 1mIU/L) is measured in response to a glucose load. Failure of suppression is characteristic of acromegaly, but the test is non-specific and may be abnormal in renal impairment, thyrotoxicosis and diabetes.

2.

In 25% of acromegalic patients, the prolactin level is elevated and this can be associated with galactorrhoea. Other pituitary hormone levels may be low because of interference with normal pituitary function by the large mass of the tumour. Baseline pituitary function should be assessed with measurements of prolactin, cortisol, thyroxine, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinising hormone (LH) and free alpha subunit.

3.

Imaging is performed once an elevated IGF-I is confirmed. MRI scanning is the modality of choice as it provides excellent anatomical definition of the tumour (see

Fig 10.7

). If the tumour is close to the optic chiasm visual field assessment should be performed.

FIGURE 10.7

MRI of the brain showing a large pituitary tumour (arrow). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

Treatment

The aim of treatment is to prevent excess GH production without interfering with normal pituitary function. Early diagnosis makes treatment easier and more effective, and IGF-I testing makes the diagnosis easier.

Acromegaly is cured when the IGF-I level is normal and GH is suppressed to less than 1.2 mIU/L after an oral glucose load. However, symptomatic relief can be obtained without complete cure.

Medical treatment with long-acting somatostatin analogues is increasingly useful, both before surgery and afterwards if removal is incomplete. Overall, surgery remains the treatment of first choice.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

1.

Long-acting somatostatin analogues, such as octreotide LAR and lanreotide autogel, are available. These drugs mimic the inhibition of GH release by somatostatin. They have the advantage that they are long-acting enough to be effective when given by subcutaneous or intramuscular injection. The usual dose of octreotide LAR is 20 mg by intramuscular injection 4-weekly, but this can be increased or decreased depending on the GH and IGF-1 levels. Lanreotide autogel is given as a starting dose of 60 mg by s.c. injection 4-weekly. Unlike somatostatin, these drugs do not significantly inhibit insulin secretion. Unless surgery or radiotherapy has cured the disease, treatment must be continued indefinitely. Symptoms such as headache, arthralgia and sweating improve after a few weeks. Biochemical remission occurs in up to 70% of patients. The drugs sometimes cause a 50–70% reduction in the size of the tumour, which can make surgery easier. Side-effects of treatment are usually relatively mild and include discomfort at the injection site, diarrhoea, anorexia, abdominal bloating and cholelithiasis.

Long-acting depot injections are now available but expensive. For this reason, they are usually reserved for patients in whom other treatment has not been completely successful or is contraindicated.

2.

Cabergoline is also available for treating acromegaly. It causes a paradoxical suppression of GH release in acromegalics, but at tolerated doses remission is not usually obtained. Side-effects include nausea, anorexia and hypotension. The drug is most often used as adjunctive treatment after radiotherapy or surgery.

SURGERY

1.

Trans-sphenoidal pituitary surgery is effective at selectively resecting the benign adenoma and preserving pituitary function in 50–80% of surgically treated cases. If cure is defined as a return of IGF-I to the normal range, then surgical cure is less often obtained. Nevertheless, symptoms are almost always greatly relieved by surgical debulking of the tumour.

2.

The perioperative mortality rate should be less than 1%.

3.

Uncommon complications include cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea, diabetes insipidus and stroke. Hypopituitarism follows eventually in about 10% of patients.

RADIOTHERAPY

Radiotherapy is usually considered as a second-line treatment where surgery has not been completely effective.

1.

Conventional radiotherapy delivers about 5000 cGy to the pituitary over 5 weeks. It works only slowly. GH levels take a year to fall by 25%. Even after 10 years few patients achieve normal IGF-I levels. Hypopituitarism is common after radiotherapy, but other side-effects are rare.

2.

Newer, more promising techniques use computerised MRI to deliver larger doses accurately to the gland (‘stereotactic radiosurgery’).

SCREEN FOR COMPLICATIONS

1.

Cardiovascular; echocardiography 5- to 10-yearly (heart failure, valve disease).

2.

Gastrointestinal; colonoscopy for polyps – at diagnosis and as required for surveillance.

3.

Thyroid; thyroid examination and TFTs regularly.

4.

Metabolic; check blood pressure, check lipids annually, fasting BSL annually.

5.

Musculoskeletal; ask about symptoms; carpal tunnel, arthropathy.

Types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus

This is a common subject for the long case since patients with diabetes are always available. A large proportion of long-case patients have type 2 diabetes, often as part of the ‘metabolic syndrome’. Diabetes usually presents a management rather than a diagnostic problem. The examiners like this disease because it tests very practical management skills.

HINT

Candidates are often tempted to unleash a set piece

diabetes long case formula

on the examiners. Don’t do it! Tailor the presentation to the actual patient you have seen.

Juvenile diabetes (immune-mediated diabetes) is called type 1 and maturity-onset diabetes (non-immune-mediated diabetes) is called type 2. Most type 1 diabetes (type 1A) is associated with autoimmune destruction of islet cells, but a small proportion of these diabetics do not have these abnormalities (type 1B).

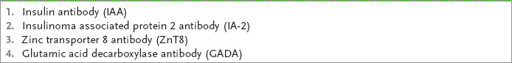

Table 10.9

lists the antibodies known to be associated with Type 1 diabetes. The cause of type 1B diabetes in these patients is not known, but it is more common in Asian populations. Type 2 diabetes is increasingly found in obese adolescents and children. More than 90% of diabetics have type 2 disease.

Table 10.9

Type 1 diabetes – associated antibodies

Don’t forget the criteria for diagnosis of diabetes mellitus – a fasting (overnight) blood sugar level (BSL) of 7.0 mmol/L or higher on at least two separate occasions or, in the absence of fasting hyperglycaemia, a 2-hour postprandial glucose level of 11.1 mmol/L or higher. Fasting blood glucose levels between 6.1 and 7.0 mmol/L are considered to represent impaired fasting glucose levels. In a patient with symptoms of diabetes a random BSL of >11.1mmol/L is diagnostic. There is evidence that complications of diabetes may occur in some populations when the fasting glucose level is over 6.1 mmol/L. An HbA1c level of >48 mmol/mol (>6.5%) is consistent with a diagnosis of diabetes.

The history

1.

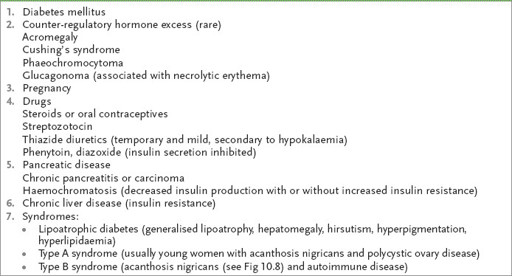

Ask about the age at which diabetes was diagnosed and its manner of presentation – thirst, polyuria and polydipsia, weight loss, infection, ketoacidosis, asymptomatic glycosuria. Remember, the rare causes of glucose intolerance (

Table 10.10

).

Table 10.10

Causes of glucose intolerance

2.

Ask about the treatment initiated at diagnosis and major changes that have occurred over time (insulin is required for survival in type 1 diabetes, which usually has an onset below age 30 years; in type 2 diabetes, control typically becomes more difficult with time).

3.

Ask about the diet prescribed (

Table 10.11

). The previous strict dietary rules using exchanges and portions have largely been abandoned, but some patients may still use them (one exchange = 15 g of carbohydrate = 60 calories = 250 kilojoules (kJs, but the definition does vary); e.g. for an average-sized male, three exchanges for each main meal and two exchanges for morning and afternoon tea and supper are required to provide an even carbohydrate distribution – 50% of the diet). Ask whether the patient knows about the glycaemic index (GI) factor. What has happened to the patient’s weight since the diagnosis was made?

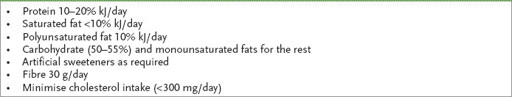

Table 10.11

Dietary recommendations for type 1 and type 2 diabetes