Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (27 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

This gives a result in mmHg/L/min or Wood units. The normal is 1.7 mmHg/L/ min.

Treatment

1.

Treatment of pulmonary hypertension that is secondary to an underlying respiratory or cardiac condition begins with an attempt to optimise treatment or fix the underlying condition.

a.

COPD:

bronchodilators, steroids, continuous oxygen.

b.

ILD:

oxygen. Aggressive treatment of an underlying connective tissue disease may halt or slow progression of the pulmonary pressures.

c.

Pulmonary embolus:

anticoagulation, vena caval filter and occasionally pulmonary embolectomy.

d.

Mitral stenosis:

valvotomy or replacement.

e.

Mitral regurgitation:

repair or replacement if left ventricular function remains reasonable.

f.

Atrial septal defect:

surgery or, if suitable, closure in the catheter laboratory (e.g. with an Amplatzer closure device). There must be evidence of reversibility of the pulmonary pressure if it is close to systemic.

g.

Eisenmenger’s syndrome:

repair of the defect responsible for the shunt is not usually possible once reversal of shunting has occurred. Consider heart and lung transplant if conservative treatment (diuretics, digoxin and sometimes ACE inhibitors) has failed.

2.

General measures include continuous oxygen, diuretics, digoxin and spironolactone for problems with right heart failure. Use of the newer endothelin receptor antagonists (bosentan), prostoglandins (iloprost) or phosphodiesterase inhibitors (sildenafil) is generally indicated for IPH and pulmonary hypertension secondary to connective tissue disease and pulmonary embolism. Bosantan has also been approved for use in Eisenmenger’s syndrome.

IDIOPATHIC (PRIMARY) PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

Treatment of this progressive and debilitating condition involves the general measures outlined above. Untreated patients have a poor survival rate: 2 to 3 years median survival from the time of diagnosis.

1.

If a vaso reactivity test is positive (response on right heart catheterisation to a short acting vasodilator), a trial of a calcium channel blocker prior to trying the newer agents in generally recommended.

2.

Bosentan has been approved for use for patients with IPH. This drug is an endothelin receptor antagonist. Endothelin-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor whose levels have been shown to be elevated in patients with IPH. Modest improvements in functional capacity and pulmonary artery pressures have been demonstrated after treatment of patients with IPH and those with underlying connective tissue disease. The drug is only available for patients with class III symptoms and a right atrial pressure of >8 mmHg. Its side-effects include teratogenicity, an increase in liver enzyme levels and possibly male infertility. Prostacyclin analogues, such as iloprost, which are taken by inhalation, can also be effective. Continuous IV epoprostenol has been shown to improve symptoms and prognosis in a number of small randomised trials for IPH patients at least. Sildenafil (a phosphodiesterase inhibitor) is a vasodilator that must not be used in combination with nitrates because of the risk of severe and prolonged hypotension.

3.

Warfarin is usually recommended because of the demonstrated risk of the formation of in situ thrombus in the pulmonary arteries.

4.

Suitable patients (severe unresponsive disease, right heart failure, young patient) should be considered for transplant. Successful outcomes have been shown with heart–lung, double lung or single lung transplants. IPH has not been found to recur

in the transplanted lung. The prognosis depends on the NYHA-WHO functional class: class I–II, 6 years; class III, 2.5 years; class IV, 6 months.

Sarcoidosis

This chronic, systemic, granulomatous disease is relatively common and patients occasionally require admission to hospital for investigation or treatment. It is an unusual lung disease in that it is less common in smokers. Although most patients present between the ages of 20 and 40 years, children and elderly people are sometimes affected. There are cases of familial sarcoidosis. At presentation 90% of patients have pulmonary involvement and 40% have other organs affected. The disorder results from an exaggerated T-helper lymphocyte response that occurs for unknown reasons and is responsible for granuloma formation and fibrosis.

The history

1.

Ask whether the patient has been admitted to hospital and if so, why. The patient may already know the diagnosis and be an outpatient undergoing further investigations or treatment, or the diagnosis may be suspected because of lymphadenopathy or changes on chest X-ray (see

Fig 6.10

). Most patients present with asymptomatic hilar adenopathy (see

Table 6.15

).

Table 6.15

Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis

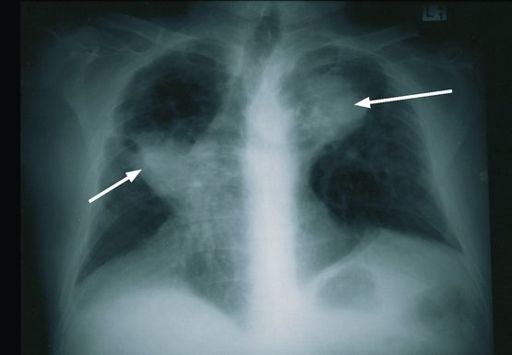

FIGURE 6.10

Massive bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (arrows). Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

2.

Ask about acute or subacute symptoms, as sarcoidosis develops in this way in about one-third of cases. The patient may have fever, weight loss, loss of appetite and malaise. The occurrence of erythema nodosum, joint symptoms and bilateral hilar adenopathy on the chest X-ray suggests an acute presentation. A combination of fever, facial nerve palsy, parotid enlargement and anterior uveitis may occur.

3.

Symptoms suggesting a more insidious onset include persistent cough and dyspnoea. If the patient has chronic sarcoidosis, it is still important to find out how he or she originally presented, as the insidious onset is more often associated with chronic sarcoidosis and the development of damage to the lungs (up to 15% develop progressive pulmonary fibrosis – ILD) and other organs.

4.

Ask about skin eruptions (e.g. erythema nodosum, plaques, maculopapular lesions and subcutaneous nodules). Erythema nodosum, fever and migratory polyarthralgias, when found in combination with hilar lymphadenopathy, may indicate Lofgren’s syndrome.

5.

Eye symptoms occur in about one-quarter of patients. The patient may have noticed blurred vision, excess tears and light sensitivity as a result of uveitis. Involvement of the lacrimal glands can cause the sicca syndrome, resulting in dry, sore eyes.

6.

Ask about nasal stuffiness, as the nasal mucosa is involved in about one-fifth of patients. Occasionally, a hoarse voice or even stridor may result from sarcoid involving the larynx.

7.

Renal involvement is uncommon but occasionally nephrolithiasis can result because of hypercalcaemia.

8.

Ask about neurological symptoms – facial nerve palsy is the most common manifestation, but psychiatric disturbances and fits may occur.

9.

Almost half the patients at some time in the course of the disease have arthralgia; even frank arthritis can occur.

10.

The patient may be aware of cardiac abnormalities. Conduction problems, including complete heart block and ventricular arrhythmias, occur in about 5% of patients. Cardioverter defibrillators are occasionally required.

11.

If the patient is female, ask about pregnancies. Sarcoidosis tends to abate in pregnancy but then flare up in the postpartum period.

12.

Enquire about gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. dysphagia from hilar adenopathy), although these are very rare. Liver involvement is common but rarely causes symptoms. The patient may know about abnormal liver function tests (usually a cholestatic picture).

13.

Ask how the diagnosis was made. The CT scan has a characteristic appearance and may have been the only investigation performed, although in most cases the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy. Specifically determine whether a lymph node biopsy or lung biopsy has been performed. Sometimes a skin or conjunctival biopsy may have been obtained to make the diagnosis. Bronchial or transbronchial lung biopsies are used to make the diagnosis in most cases. Occasionally, mediastinoscopy with lymph node biopsy is needed to make the diagnosis. Cardiac MRI can be used to look for myocardial involvement.

14.

Ask about treatment. Find out whether the patient has been receiving steroids and what dose is currently being taken. Various other treatments may have been tried, including NSAIDs, cyclosporin and cyclophosphamide.

The examination

1.

Begin with an examination of the skin.

a.

You might be lucky enough to find erythema nodosum. These raised red or purple lesions are most commonly found on the lower limbs. They resolve spontaneously after 3 or 4 weeks.

b.

Look at the face, back and extremities for maculopapular eruptions. These are elevated spots less than 1 cm in diameter that have a waxy, flat top. There may also be lupus pernio on the face (see

Fig 6.11

). These are purple swollen nodules with a shiny surface, which particularly affect the nose, cheeks, eyelids and ears. They may make the nose appear bulbous; occasionally the mucosa of the nose may be involved and the underlying bone can be destroyed. Lupus pernio sometimes also involves the fingers and knees. Pink nodules may be found in old scars.

FIGURE 6.11

Lupus pernio. The nose shows typical scaly violaceous swelling. F Ferri, Sarcoidosi–lupus perni.

Ferri’s color atlas and text of clinical medicine

. Fig 11.4. Elsevier, 2009, with permission.

2.

Examine the eyes for signs of uveitis. Yellow conjunctival nodules may be present. Examine the fundi for papilloedema. Feel the parotids. Uveoparotid fever presents with uveitis, parotid swelling and seventh cranial nerve palsy.

3.

Next examine the respiratory system. Most commonly, physical examination of the chest reveals no abnormality. Look particularly for signs of interstitial lung disease; basal end-inspiratory crackles may be present. Pleural effusions occur rarely.

4.

Next examine all the lymph nodes. Lymphadenopathy is sometimes generalised.

5.

Now examine the abdomen for hepatomegaly (20%) and splenomegaly (up to 40%).

6.

Examine the joints for signs of arthritis, which is almost always non-deforming.

7.

Examine the nervous system. Look particularly for facial nerve palsy.

8.

Feel the pulse (heart block or arrhythmia) and look for signs of right ventricular failure or cardiomyopathy. Note the presence of a pacemaker or defibrillator box.

Investigations

1.

A full blood count may reveal lymphocytopenia and sometimes eosinophilia.

2.

The ESR is often raised. There may be hyperglobulinaemia.

3.

The ACE level is raised in about two-thirds of patients with active sarcoidosis but unfortunately is not diagnostic; ACE is also sometimes elevated (5%) in healthy persons or those with primary biliary cirrhosis, leprosy, atypical mycobacterial infection, miliary tuberculosis, silicosis, acute histoplasmosis and hyperparathyroidism. ACE is not elevated in patients with malignancies (e.g. lymphoma). Hypercalcaemia and, more commonly, hypercalciuria may be present.