Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (58 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

4.

Ask whether oral hypoglycaemic drugs have been used or are being taken.

5.

Ask about insulin treatment – how much and when taken. The usual dose is 0.5 units/kg/day, with 40% of the dose comprising a long-acting insulin. Also ask where the insulin is injected and by whom, and find out the type of insulin syringe used (e.g. a pen injector).

6.

Ask about the progress of the disease:

a.

assessment of control adequacy – does the patient use a home blood glucose monitoring meter? If the patient is blind, is the glucometer a talking version? Which glucose reagent strip is used and which meter? (Remember that different meters require different reagent strips.) Enquire how often the test is done, the usual results, at what time of day the test is performed (pre- or postprandial or both) and whether the dose is adjusted at other times (e.g. gastrointestinal upset). Ask about recent glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1

c

) results. Ask about symptoms of poor control:

i.

hyperglycaemia – polyuria, thirst, weight loss, intermittent blurring of vision, hospital admissions with ketoacidosis (type 1 diabetes only)

ii.

hypoglycaemia/hypoglycaemia awareness – ask the patient to describe the symptoms and how they are managed; ask specifically about morning headaches, morning lethargy and night sweats (symptoms suggestive of nocturnal hypoglycaemia), weight gain and seizures; ask about the time of day in relation to food, alcohol, exercise and insulin injection

b.

involvement of other systems:

i.

vascular system – ischaemic heart disease, intermittent claudication, cerebrovascular disease

ii.

nervous system – peripheral neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy (causing erectile dysfunction, fainting, nocturnal diarrhoea), amyotrophy

iii.

eyes – regular visits to an ophthalmologist or retinal photography at the diabetes clinic and treatment received (ask especially about laser treatment)

iv.

renal system – dysuria, nocturia, oedema, hypertension; is the patient taking an ACE inhibitor or AR blocker for renal protection; has there been proteinuria?

v.

skin – boils, vaginitis and balanitis,

Candida

, necrobiosis lipoidica.

7.

Ask about drug history – steroids, thiazides, oral contraceptives, beta-blockers.

8.

Ask about associated other diseases – history of pancreatitis, Cushing’s syndrome, acromegaly.

9.

Enquire about social background – type of work, living conditions (living alone or with family), coping with giving insulin (associated blindness etc.), eating habits, financial situation, driving (type of licence held).

10.

Ask about variations in weight and a regular exercise program. Have diet and exercise led to a fall in weight since the diabetes was diagnosed?

11.

Ask about cardiovascular risk factors, including family history, serum cholesterol level, smoking and hypertension, and drug and non-drug attempts at control of these factors (except family history).

12.

Enquire about family history of diabetes and obstetric history (e.g. big babies, stillbirths), and other risk factors for type 2 diabetes (see

Table 10.12

).

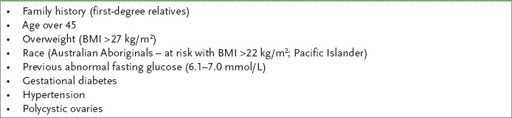

Table 10.12

Risk factors for type 2 diabetes

13.

Ask whether the patient has an ‘action plan’ for hypoglycaemic symptoms and what this involves.

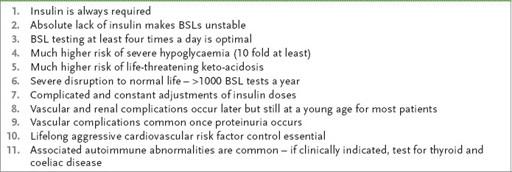

Table 10.13

Particular considerations for type 1 diabetes

The examination

Detailed examination is essential, looking specifically for complications of the disease (

Figs 10.8

and

10.9

). In particular, don’t forget to look at the retina. Inspect the feet and assess for peripheral neuropathy. Test the urine. If the patient is obese, assess BMI and waist circumference.

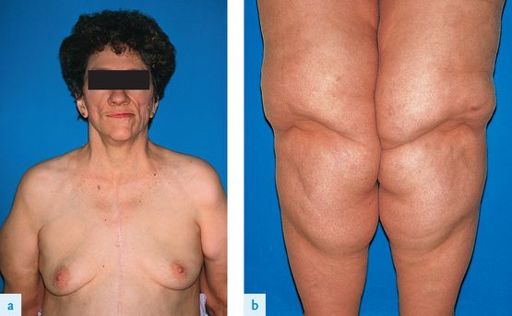

FIGURE 10.8

Acanthosis nigricans (a) View of the axillar region. (b) View of the neck and anterior chest wall. I Tonguc, S Cenc, D Iscen, K Yildiz. Acanthosis nigricans and an alternative for its surgical therapy.

Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery

, 2008, 62(1):148–150, with permission.

FIGURE 10.9

Partial lipodystrophy, acquired. (a) Face (b) hypertrophy of subcutaneous fat on the lower half of the body. W D James, T Berger, D Elston.

Andrews’ diseases of the skin: clinical dermatology

. 11th edn. Fig 23-9. Saunders, Elsevier, 2011, with permission.

Management

The general aim is to regulate diet, exercise and insulin so as to allow the patient to lead a normal life while avoiding short- and long-term complications.

In adults with type 1 diabetes, multiple injection regimens are preferred because the improved control prevents or retards the progression of complications.

THE NEWLY DIAGNOSED PATIENT WITH DIABETES

The major management decision here is whether insulin is required. In some cases this will be obvious (e.g. for the type 1 patient with ketoacidosis), but for many elderly obese diabetics the position is not so clear. If insulin is not indicated at presentation, attempt to gain control first by weight loss and diet, followed by oral hypoglycaemic agents.

1.

Weight loss

. Weight loss to achieve ideal body weight increases insulin sensitivity. Abdominal obesity (waist–hip ratio >0.9 for women and >0.8 for men) increases the risk of metabolic complications. Realise that there is some disagreement about the ideal diet, but achieving ideal weight is essential.

2.

Diet

. The recommended diet (see

Table 10.11

) should be tailored to the patient’s requirements and activities. For example, kilojoule recommendations for a 20-year-old man undertaking normal activities are 175 kJ/kg of body weight and for a 75-year-old man are 140 kJ/kg. Distribution of carbohydrate should be worked out on an individual basis. Fat intake should be kept to ≤30% of kilojoules for patients who are not overweight and considerably less for obese patients. The distribution of kilojoules is more important for insulin-requiring patients, who should usually have about 20% for breakfast, 35% for lunch, 30% for dinner and 15% for supper. Patients who use short-acting insulin before each meal may be able to vary the insulin dose to suit the meal. The diet should include high-fibre foods and monounsaturated fats. Polyunsaturated fats can raise triglyceride levels but monounsaturates tend to reduce them. Patients with nephropathy may be advised to restrict protein intake, usually to about 10% of kilojoule intake.

3.

Oral hypoglycaemic agents

. The use of oral hypoglycaemic agents is first line treatment for type 2 patients where diet has not been successful.

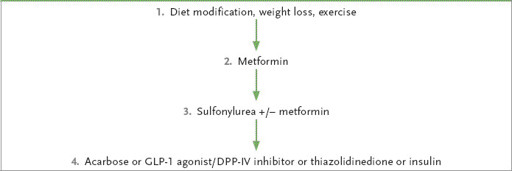

Table 10.14

shows the NHMRC treatment chart for type 2 diabetes.

Table 10.14

Major secondary causes of osteoporosis

a.

Metformin is the only available biguanide and is regarded as the agent of choice in the obese patient with type 2 diabetes. They are contra-indicated for patients with an eGFR < 30mL/min/1.73m². Side-effects of biguanides include:

i.

diarrhoea, anorexia, nausea and occasionally vomiting

ii.

vitamin B

12

malabsorption

iii.

lactic acidosis (the risk is increased in the elderly and in patients with cardiovascular, liver and kidney disease); the drug is contraindicated in heart failure

iv.

interaction with radiocontrast materials; the drug should be stopped on the day of a procedure requiring contrast and for 48 hours afterwards

v.

Metformin rarely causes hypoglycaemia and there is a synergistic effect when it is used in combination with sulfonylureas.

b.

Sulfonylureas include first-generation drugs (e.g. chlorpropamide and tolbutamide) and second-generation drugs (e.g. gliclazide, used for obese patients; glipizide, used for thin patients; and glibenclamide). Second-generation drugs are as effective as the first-generation ones and are associated with fewer drug interactions. The mechanism of action of sulfonylureas is to increase insulin action peripherally and to increase insulin secretion. Side-effects of sulfonylureas include:

i.

possibly an increase in the cardiovascular death rate – this fear seems not to have been well founded, as the UKPDS (see below) did not find any increase in cardiovascular mortality for patients on these drugs

ii.

prolonged hypoglycaemia – this is greatest with glibenclamide, which is therefore not recommended for those over the age of 60; gliclazide and glipizide are as effective and are safer