Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (93 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

Eyes

‘Please examine this man’s eyes.’

Method (see

Table 16.48

)

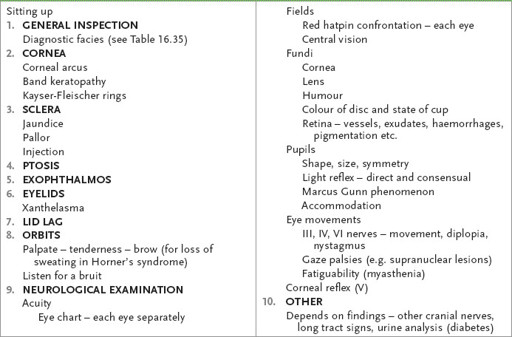

Table 16.48

Medical eye examination

1.

Always inspect the eyes first, with the patient sitting over the end of the bed facing you at eye level if possible. Note any corneal abnormalities, such as band keratopathy (in hypercalcaemic states) or Kayser-Fleischer rings (Wilson’s disease). Look at the sclerae for colour (e.g. jaundice, blue in osteogenesis imperfecta), pallor, injection and telangiectasia. Inspect carefully for subtle ptosis or strabismus. Look for exophthalmos from behind and above the patient, as well as in front.

2.

Proceed then as for the cranial nerve eye examination, testing acuity, fields and pupils, and then performing fundoscopy.

3.

Begin fundoscopy by examining the cornea and lens, and then the retina. Note any corneal, lens or humor abnormalities. Look for retinal changes of diabetes mellitus (see

Table 16.43

) and hypertension (see

Table 16.7

). Also carefully inspect for optic atrophy, papilloedema, angioid streaks (see p. 381), retinal detachment, central vein or artery thrombosis and retinitis pigmentosa.

FIGURE 16.43

Diffuse goitre. G Medeiros-Neto, R Y Camargo, E K Tomimori. Thyroid disorders and diseases: approach to and treatment of goiters.

Medical Clinics of North America

, 2012. 96(2):351–368, Fig 3.

4.

Test eye movements. Also look for fatiguability of eye muscles by asking the patient to look up at your hatpin for half a minute (myasthenia gravis). Alternatively ask the patient to close the eyes tightly; if positive (the peek sign), within 30 seconds the lid margin will begin to separate, showing the sclera. Test for lid lag if you suspect hyperthyroidism.

5.

Test the corneal reflex.

6.

Palpate the orbits for tenderness and auscultate the eyes with the bell of the stethoscope (the eye being tested is shut, the other is open and the patient is asked to stop breathing).

7.

Do not forget that the patient may have a glass eye. Suspect this if visual acuity is zero in one eye and no pupillary reaction is apparent. Lengthy attempts to examine the fundus of a glass eye are embarrassing (and not uncommon).

One-and-a-half syndrome

This is rare but important to recognise. These patients have a horizontal gaze palsy when looking to one side (the ‘one’) plus impaired adduction on looking to the other

side (the ‘and-a-half’). Other features often include turning out (exotropia) of the eye opposite the side of the lesion (paralytic pontine exotropia). The one-and-a-half syndrome can be caused by a stroke (infarct), plaque of multiple sclerosis or tumour in the dorsal pons.

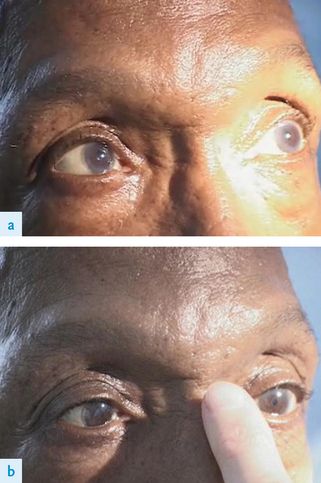

Horner’s syndrome

If you find a partial ptosis and a constricted pupil (which reacts normally to light), Horner’s syndrome is likely (see

Table 16.49

,

Fig 16.85

). Proceed as follows.

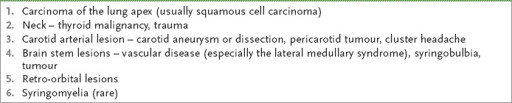

Table 16.49

Causes of Horner’s syndrome

FIGURE 16.85

Horner’s syndrome (right eye abnormal). M Yanoff, J S Duker.

Ophthalmology

, 3rd edn. Fig 9.19.7. Mosby, Elsevier, 2008, with permission.

1.

Test for a difference in sweating over each brow with the back of your finger (even though your brow is usually more sweaty than the patient’s); this occurs only when the lesion is proximal to the carotid bifurcation. Absence of sweating differences does not exclude the diagnosis of Horner’s syndrome.

2.

Next, examine the appropriate cranial nerves to exclude the lateral medullary syndrome:

a.

nystagmus (to the side of the lesion)

b.

ipsilateral fifth (pain and temperature), ninth and tenth cranial nerve lesions

c.

ipsilateral cerebellar signs

d.

contralateral pain and temperature loss over the trunk and limbs.

3.

Ask the patient to speak and note any hoarseness (which may be caused by recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy from a chest lesion or a cranial nerve lesion).

4.

Look at the hands for clubbing. Test finger abduction to screen for a lower trunk brachial plexus (C8, T1) lesion.

5.

If there are signs of hoarseness or a lower trunk brachial plexus lesion, proceed to a respiratory examination, concentrating on the apices for signs of lung carcinoma.

6.

Examine the neck for lymphadenopathy, thyroid carcinoma and a carotid aneurysm or bruit (e.g. fibromuscular dysplasia causing dissection).

7.

As syringomyelia may rarely cause this syndrome, finish off the assessment by examining for dissociated sensory loss. Remember, this lesion may cause a

bilateral

Horner’s syndrome (a trap for the unwary).

Notes on the cranial nerves

First (olfactory) nerve (p. 409)

CAUSES OF ANOSMIA

Bilateral

1.

Upper respiratory tract infection (most common).

2.

Meningioma of the olfactory groove (late).

3.

Ethmoid tumours.

4.

Head trauma (including cribriform plate fracture).

5.

Meningitis.

6.

Hydrocephalus.

7.

Congenital – Kallmann’s syndrome (hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism).

Unilateral

1.

Meningioma of the olfactory groove (early).

2.

Head trauma.

Second (optic) nerve (p. 409)

LIGHT REFLEX

Constriction of the pupil in response to light is relayed via the optic nerve and tract, the superior quadrigeminal brachium, the Edinger-Westphal nucleus and its efferent parasympathetic fibres, which terminate in the ciliary ganglion. There is no cortical involvement.

ACCOMMODATION REFLEX

Constriction of the pupil with accommodation originates in the cortex (in association with convergence) and is relayed via parasympathetic fibres in the third nerve.

CAUSES OF ABSENT LIGHT REFLEX BUT INTACT ACCOMMODATION REFLEX

1.

Midbrain lesion (e.g. Argyll Robertson pupil).

2.

Ciliary ganglion lesion (e.g. Adie’s pupil).

3.

Parinaud’s syndrome.

4.

Bilateral anterior visual pathway lesions (i.e. bilateral afferent pupil deficits).

CAUSES OF ABSENT CONVERGENCE BUT INTACT LIGHT REFLEX

1.

Cortical lesion (e.g. cortical blindness).

2.

Midbrain lesions (rare).

Pupil abnormalities

CAUSES OF CONSTRICTION

1.

Horner’s syndrome.

2.

Argyll Robertson pupil.

3.

Pontine lesion (often bilateral, but reactive to light).

4.

Narcotics.

5.

Pilocarpine drops.

6.

Old age.

CAUSES OF DILATION

1.

Mydriatics, atropine poisoning or cocaine.

2.

Third nerve lesion.

3.

Adie’s pupil.

4.

Iridectomy, lens implant, iritis.

5.

Post-trauma, deep coma, cerebral death.

6.

Congenital.

Visual field defects (see

Fig 16.86

)

Adie’s syndrome

CAUSE

Lesion in the efferent parasympathetic pathway.

SIGNS

1.

Dilated pupil.

2.

Decreased or absent reaction to light (direct and consensual).

3.

Slow or incomplete reaction to accommodation with slow dilation afterwards.

4.

Decreased tendon reflexes.

5.

Patients are commonly young women.

Argyll Robertson pupil (

Fig 16.87

)

CAUSE

Lesion of the iridodilator fibres in the midbrain, as in:

FIGURE 16.87

Argyll Robertson pupil. (a) Lack of pupillary constriction to light. (b) Pupillary constriction to accommodation. T A Aziz, R P Holman. The Argyll Robertson pupil.

American Journal of Medicine

, 2010. 123(2):120–121, Fig 1. Elsevier, with permission.