Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training (91 page)

Read Examination Medicine: A Guide to Physician Training Online

Authors: Nicholas J. Talley,Simon O’connor

Tags: #Medical, #Internal Medicine, #Diagnosis

FIGURE 16.75

X-ray of the feet of a patient with early psoriatic arthritis. Note the large erosions and absence of osteoporosis. There is already some joint deformity, and a spiculated bony growth is visible. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 16.76

X-ray of the feet of a patient with severe psoriatic arthritis:

arthritis mutilans

. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 16.77

X-ray of the feet of a patient with severe gouty arthritis. Note the relative preservation of the joint spaces with erosions and overhanging edges. The area of the junction of the forefoot and midfoot has numerous erosions, which is a common finding. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 16.78

X-ray of the feet of a patient with diabetic arthropathy. Note the gross joint destruction – Charcot’s joints. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

The back

‘This 47-year-old man has had back pain for many years. Please examine him.’

Or

‘This 47-year-old man has ankylosing spondylitis. Please examine him and assess the severity of his disease.’ (

Fig 16.79

)

FIGURE 16.79

Ankylosing spondylitis. Note the occiput-to-wall distance.

Method

1.

The initial inspection confirms that this is a case of ankylosing spondylitis (see

Table 16.46

). Ask the patient to undress to his underpants and stand up. Look for deformity, inspecting from both the back and the side, particularly for loss of kyphosis and lumbar lordosis. Palpate each vertebral body for tenderness and palpate for muscle spasm.

Table 16.46

The seronegative spondyloarthropathies

| | HLA-B27 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 95% |

| Psoriatic spondylitis | 50% |

| Reactive arthritis, including Reiter’s syndrome | 80% |

| Enteropathic arthritis | 75% |

2.

Test movement next. Measure the finger–floor distance (inability to touch the toes suggests early lumbar disease).

3.

Next look at extension, lateral flexion and rotation of the back. Get him to run each hand down the corresponding thigh to test lateral flexion.

4.

Ask whether you may perform a modified Schober’s test. This involves identifying the level of the posterior iliac spine on the vertebral body (approximately at L5). Place a mark 5 cm below this point and another 10 cm above this point. Ask the patient to touch his toes. There should normally be an increase of 5 cm or more in the distance between the marks. In ankylosing spondylitis there will be little separation of the marks, since all the movement is taking place at the hips.

HINT

Small adhesive paper or plastic strips are popular as markers: do not mark the patient with a pen.

5.

Next test the occiput-to-wall distance. Ask the patient to place his heels and back against the wall and ask him to touch the wall with the back of his head without raising his chin above the carrying level; inability to touch the wall suggests cervical involvement and the distance from occiput to wall is measured.

HINT

It is a good idea to know why testing of occiput-to-wall distance is performed: it is to assess progression of the disease at clinic visits.

6.

Before asking the patient to lie down, test for active sacroiliac disease by springing the anterior superior iliac spines. Pain felt in the region of the sacroiliac joints suggests activity. A simple (and unreliable) test for sacroiliac disease is to push with the heel of the hand on the sacrum and note the presence of tenderness in either sacroiliac joint on springing. (

Note:

Usually there is bilateral disease in ankylosing spondylitis.)

7.

Ask the patient to lie on his stomach. Examine the heels for Achilles tendinitis and plantar fasciitis, which are characteristic of the spondyloarthropathies. Evaluate the other large joints, particularly the knees, hips and shoulders.

8.

Examine the chest for decreased lung expansion (chest expansion of less than 3 cm at the nipple line suggests early costovertebral involvement) and for signs of apical fibrosis. Examine the heart for aortic regurgitation, mitral valve prolapse and evidence of conduction defects, and the eyes for uveitis.

9.

Examine the gastrointestinal system for evidence of inflammatory bowel disease and for signs of amyloid deposition (e.g. hepatosplenomegaly, abnormal urine analysis results). Remember also to check for signs of psoriasis and Reiter’s syndrome, which may cause spondylitis and unilateral sacroiliitis. Rarely, patients with ankylosing spondylitis have a cauda equina compression. X-ray changes are described in

Table 16.47

and illustrated in

Figs 16.80

–

16.82

.

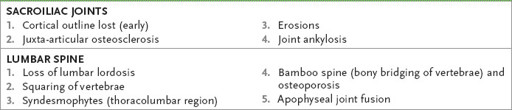

Table 16.47

X-ray changes in ankylosing spondylitis

FIGURE 16.80

X-ray of the pelvis of a patient with Reiter’s syndrome. Note the loss of joint space in the two sacroiliac joints and lumbar spine ankylosis. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.

FIGURE 16.81

Lateral chest X-ray of a patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Note the loss of joint space and squaring of the vertebrae. Figure reproduced courtesy of The Canberra Hospital.