Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (15 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

“Rudolph” was reprinted as a Christmas booklet sporadically until 1947. That year, a friend of May’s, Johnny Marks, decided to put the poem to music. One professional singer after another declined the opportunity to record the song, but in 1949, Gene Autry consented. The Autry recording rocketed to the top of the

Hit Parade

. Since then, three hundred different recordings have been made, and more than eighty million records sold. The original Gene Autry version is second only to Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” as the best-selling record of all time.

Rudolph became an annual television star, and a familiar Christmas image in Germany, Holland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, England, Spain, Austria, and France—many of the countries whose own lore had enriched the international St. Nicholas legend. Perhaps most significantly, “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer” has been called by sociologists the only new addition to the folklore of Santa Claus in the twentieth century.

At the table

Table Manners: 2500

B.C

., Near East

Manners are a set of rules that allow a person to engage in a social ritual—or to be excluded from one. And table manners, specifically, originated in part as a means of telling a host that it was an honor to be eating his or her meal.

Etiquette watchers today claim that dining standards are at an all-time low for this century. As a cause, they cite the demise of the traditional evening meal, when families gathered to eat and parents were quick to pounce on errant behavior. They also point to the popularity of ready-to-eat meals (often consumed quickly and in private) and the growth of fast-food restaurants, where, at least among adolescents, those who display table manners can become social outcasts. When young people value individual statement over social decorum, manners don’t have a chance.

Evidence of the decline comes from surprisingly diverse quarters. Army generals and corporate executives have complained that new recruits and MBA graduates reveal an embarrassing confusion about formal manners at the table. This is one reason cited for the sudden appearance of etiquette books on best-seller lists.

The problem, though, is not new. Historians who chart etiquette practices claim that the deterioration of formal manners in America began a long time ago—specifically, and ironically, with Thomas Jefferson and his fondness for equality and his hatred of false civility. Jefferson, who had impeccable manners himself, often deliberately downplayed them. And during

his presidency, he attempted to ease the rules of protocol in the capital, feeling they imposed artificial distinctions among people created equal.

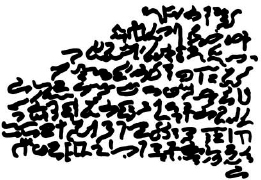

From

The Instructions of Ptahhotep,

c. 2500 B.C., history’s first code of correct behavior. To ingratiate one to a superior, the author advises: “Laugh when he laughs

.”

But before manners can be relaxed or abused, they have to be conceived and formalized, and those processes originated centuries ago.

Early man, preoccupied with foraging for food, which was scarce, had no time for manners; he ate stealthily and in solitude. But with the dawn of agriculture in the Near East, about 9000

B.C

., man evolved from hunter-gatherer to farmer. He settled down in one place to a more stable life. As food became plentiful, it was shared communally, and rules were developed for its preparation and consumption. One family’s daily habits at the table became the next generation’s customs.

Historical evidence for the first code of correct behavior comes from the Old Kingdom of Egypt, in a book,

The Instructions of Ptahhotep

(Ptahhotep was grand vizier under the pharaoh Isesi). Written about 2500

B.C

., the manuscript on manners now resides in a Paris antiquities collection.

Known as the “Prisse papyrus” —not that its dictates on decorum are prissy; an archaeologist by that name discovered the scrolls—the work predates the Bible by about two thousand years. It reads as if it was prepared as advice for young Egyptian men climbing the social ladder of the day. In the company of one’s superior, the book advises, “Laugh when he laughs.” It suggests overlooking one’s quiddities with a superior’s philosophy, “so thou shalt be very agreeable to his heart.” And there are numerous references to the priceless wisdom of holding one’s tongue, first with a boss: “Let thy mind be deep and thy speech scanty,” then with a wife: “Be silent, for it is a better gift than flowers.”

By the time the assemblage of the Bible began, around 700

B.C

, Ptahhotep’s two-thousand-year-old wisdom had been well circulated throughout the Nile delta of Egypt and the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia. Religious scholars have located strong echoes of

The Instructions

throughout the Bible, especially in Proverbs and Ecclesiastes—and particularly regarding the preparation and consumption of food.

Fork: 11th Century, Tuscany

Roman patricians and plebeians ate with their fingers, as did all European peoples until the dawning of a conscious fastidiousness at the beginning of the Renaissance. Still, there was a right and a wrong, a refined and an uncouth, way to go about it. From Roman times onward, a commoner grabbed at his food with five fingers; a person of breeding politely lifted it with

three

fingers—never soiling the ring finger or the pinkie.

Evidence that forks were not in common use in Europe as late as the sixteenth century—and that the Roman “three-finger rule” still was—comes from an etiquette book of the 1530s. It advises that when dining in “good society,” one should be mindful that “It is most refined to use only three fingers of the hand, not five. This is one of the marks of distinction between the upper and lower classes.”

Manners are of course relative and have differed from age to age. The evolution of the fork, and resistance against its adoption, provides a prime illustration.

Our word “fork” comes from the Latin

furca

, a farmer’s pitchfork. Miniatures of these ancient tools, the oldest known examples, were unearthed at the archaeological site of Catal Hoyuk in Turkey; they date to about the fourth millennium

B.C

. However, no one knows precisely what function miniature primitive pitchforks served. Historians doubt they were tableware.

What is known with certainty is that small forks for eating first appeared in eleventh-century Tuscany, and that they were widely frowned upon. The clergy condemned their use outright, arguing that only human fingers, created by God, were worthy to touch God’s bounty. Nevertheless, forks in gold and silver continued to be custom made at the request of wealthy Tuscans; most of these forks had only two tines.

For at least a hundred years, the fork remained a shocking novelty. An Italian historian recorded a dinner at which a Venetian noblewoman ate with a fork of her own design and incurred the rebuke of several clerics present for her “excessive sign of refinement.” The woman died days after the meal, supposedly from the plague, but clergymen preached that her death was divine punishment, a warning to others contemplating the affectation of a fork.

In the second century of its Tuscan incarnation, the two-prong fork was introduced to England by Thomas à Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury and British chancellor under Henry II. Renowned for his zeal in upholding ecclesiastical law, Becket escaped England in 1164 to avoid trial by the lay courts; when he returned six years later, after pardon by the king, the archbishop was familiar with the Italian two-tined dining fork. Legend has it that noblemen at court employed them preferentially for dueling.

By the fourteenth century, the fork in England was still nothing more than a costly, decorative Italian curiosity. The 1307 inventory of King

Edward I reveals that among thousands of royal knives and hundreds of spoons, he owned a mere seven forks: six silver, one gold. And later that century, King Charles V of France owned only twelve forks, most of them “decorated with precious stones,” none used for eating.

People were picking up their food in a variety of accepted ways. They speared it with one of a pair of eating knives, cupped it in a spoon, or pinched it with the correct three fingers. Even in Italy, country of the fork’s origin, the implement could still be a source of ridicule as late as the seventeenth century—especially for a man, who was labeled finicky and effeminate if he used a fork.

Women fared only slightly better. A Venetian publication of 1626 recounts that the wife of the doge, instead of eating properly with knife and fingers, ordered a servant to “cut her food into little pieces, which she ate by means of a two-pronged fork.” An affectation, the author writes, “beyond belief!” Forks remained a European rarity. A quarter century later, a popular etiquette book thought it necessary to give advice on something that was not yet axiomatic: “Do not try to eat soup with a fork.”

When, then, did forks become the fashion? And why?

Not really until the eighteenth century, and then, in part, to emphasize class distinction. With the French Revolution on the horizon, and with revolutionaries stressing the ideals of “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity,” the ruling French nobility increased their use of forks—specifically the four-tined variety. The fork became a symbol of luxury, refinement, and status. Suddenly, to touch food with even three bare fingers was gauche.

An additional mark distinguishing classes at the dining table was individual place settings—each aristocrat present at a meal received a full complement of cutlery, plates, and glasses. Today, in even the poorest families, separate dining utensils are commonplace. But in eighteenth-century Europe, most people, and certainly the poorer classes, still shared communal bowls, plates, and even drinking glasses. An etiquette book of that period advises: “When everyone is eating from the same dish, you should take care not to put your hand into it before those of higher rank have done so.” There were, however, two table implements that just about everyone owned and used: the knife and the spoon.

Spoon: 20,000 Years Ago, Asia

Spoons are millennia older than forks, and never in their long history did they, or their users, suffer ridicule as did forks and their users. From its introduction, the spoon was accepted as a practical implement, especially for eating liquids.

The shape of early spoons can be found in the origin of their name. “Spoon” is from the Anglo-Saxon

spon

, meaning “chip,” and a spoon was a thin, slightly concave piece of wood, dipped into porridge or soupy foods not liquid enough to sip from a bowl. Such spoons have been unearthed

in Asia dating from the Paleolithic Age, some twenty thousand years ago. And spoons of wood, stone, ivory, and gold have been found in ancient Egyptian tombs.

Upper-class Greeks and Romans used spoons of bronze and silver, while poorer folk carved spoons of wood. Spoons preserved from the Middle Ages are largely of bone, wood, and tin, with many elaborate ones of silver and gold.

In Italy during the fifteenth century, “apostle spoons” were the rage. Usually of silver, the spoons had handles in the figure of an apostle. Among wealthy Venetians and Tuscans, an apostle spoon was considered the ideal baptismal gift; the handle would bear the figure of the child’s patron saint. It’s from this custom that a privileged child is said to be born with a silver spoon in its mouth, implying, centuries ago, that the family could afford to commission a silver apostle’s spoon as a christening gift.

Knife: 1.5 Million Years Ago, Africa and Asia

In the evolution to modern man,

Homo erectus

, an early upright primate, fashioned the first standardized stone knives for butchering prey. Living 1.5 million years ago, he was the first hominid with the ability to conceive a design and then labor over a piece of stone until the plan was executed to his liking. Since that time, knives have been an important part of man’s weaponry and cutlery. They’ve changed little over the millennia, and even our word “knife” is recognizable in its Anglo-Saxon antecedent,

cnif

.

For centuries, most men owned just one knife, which hung at the waist for ready use. One day they might use it to carve a roast, the next to slit an enemy’s throat. Only nobles could afford separate knives for warfare, hunting, and eating.

Early knives had pointed tips, like today’s steak knives. The round-tip dinner knife, according to popular tradition, originated in the 1630s as one man’s attempt to put an end to a commonplace but impolite table practice.

The man was Armand Jean du Plessis, better known as Duc de Richelieu, cardinal and chief minister to France’s Louis XIII. He is credited with instituting modern domestic espionage, and through iniquitous intrigues and shrewd statesmanship he catapulted France to supreme power in early seventeenth-century Europe. In addition to his preoccupation with state matters and the acquisition of personal authority, Richelieu stressed formal manners, and he bristled at one table practice of the day. During a meal, men of high rank used the pointed end of a knife to pick their teeth clean—a habit etiquette books had deplored for at least three hundred years. Richelieu forbade the offense at his own table and, according to French legend, ordered his chief steward to file the points off house knives. Soon French hostesses, also at a loss to halt the practice, began placing orders for knives like Richelieu’s. At least it is known factually that by the close of

the century, French table settings often included blunt-ended knives.