Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things (65 page)

Read Extraordinary Origins of Everyday Things Online

Authors: Charles Panati

Tags: #Reference, #General, #Curiosities & Wonders

In November 1914, a patent was awarded for the Backless Brassiere. Aided by a group of friends, Mary Jacobs produced several hundred handmade garments; but without proper marketing, the venture soon collapsed. By chance, she was introduced socially to a designer for the Warner Brothers Corset Company of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Mary Jacobs mentioned her invention, and when the firm offered $1,500 for patent rights, she accepted. The patent has since been valued at $15 million.

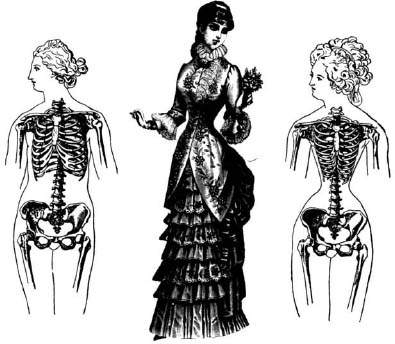

Before the bra. A nineteenth-century depiction of the harmful skeletal effects from tight corseting

.

Innovations on Mary Jacobs’s design followed. Elastic fabric was introduced in the ’20s, and the strapless bra, as well as standard cup sizes, in the ’30s. The woman largely responsible for sized bras was Ida Rosenthal, a Russian-Jewish immigrant who, with the help of her husband, William, founded Maidenform.

During the “flapper era” of the ’20s, fashion dictated a flat-chested, boyish look. Ida Rosenthal, a seamstress and dress designer, bucked the trend, promoting bust-flattering bras. Combining her own design experience and paper-patterns, she grouped American women into bust-size categories and produced a line of bras intended to lift the female figure through every stage from puberty to maturity. Her belief that busts would return to fashion built a forty-million-dollar Maidenform industry. Asked during the ’60s, when young women were burning bras as a symbol of female liberation, if the action signaled the demise of the brassiere business, Ida Rosenthal answered, “We’re a democracy. A person has the right to be dressed or undressed.” Then she added, “But after age thirty-five a woman hasn’t got the figure to wear no support. Time’s on my side.”

Hosiery: 4th Century

B.C

., Rome

Sock. Hose. Stocking. However we define these related words today, or choose to use them interchangeably in a sentence, one thing is certain: originally they were not the items they are now. The sock, for instance, was a soft leather slipper worn by Roman women and effeminate men. Hose covered the leg but not the foot. The word “stocking” does not appear in the vocabulary of dress until the sixteenth century, and its evolution up the leg from the foot took hundreds of years.

The history of men’s and women’s “socks” begins with the birth of garments that were “put on” rather than merely “wrapped around.”

The first “put on” items were worn by Greek women around 600

B.C

.: a low, soft sandal-like shoe that covered mainly the toes and heel. (See page 294.) Called a

sykhos

, it was considered a shameful article for a man to wear and became a favorite comic theater gimmick, guaranteed to win a male actor a laugh.

Roman women copied the Greek

sykhos

and Latinized its name to

soccus

. It, too, was donned by Roman mimes, making it for centuries standard comedy apparel, as baggy pants would later become the clown’s trademark.

The

soccus

sandal was the forerunner both of the word “sock” and of the modern midcalf sock. From Rome, the soft leather

soccus

traveled to the British Isles, where the Anglo-Saxons shortened its name to

soc

. And they discovered that a soft

soc

worn inside a coarse boot protected the foot from abrasion. Thus, from its home inside the boot, the

soc

was on its way to becoming the modern sock. Interestingly, the Roman

soccus

also traveled to Germany, where it was worn inside a boot, its spelling abbreviated to

socc

, which until the last century meant both cloth footwear and a lightweight shoe.

Hose

. In ancient times in warm Mediterranean countries, men wore wraparound skirts, having no need for the leg protection of pants. In the colder climates of Northern Europe, though, Germanic tribes wore loose-fitting trousers reaching from waist to ankle and called

heuse

. For additional warmth, the fabric was commonly crisscrossed with rope from ankle to knee, to shield out drafts.

This style of pants was not unique to Northern Europeans. When Gaius Julius Caesar led his Roman legions in the first-century

B.C

. conquest of Gaul, his soldiers’ legs were protected from cold weather and the thorns and briers of northwestern forests by

hosa

—gathered leg coverings of cloth or leather worn beneath the short military tunic. The word

hosa

became “hose,” which for many centuries denoted gathered leg coverings that reached down only to the ankles.

Logically, it might seem that in time, leg hose were stitched to ankle socks

to form a new item, stockings. However, that is not what happened. The forerunner of modern stockings are neither socks nor hose but, as we’re about to see,

undones

.

Stockings: 5th Century, Rome

By

A.D

. 100, the Romans had a cloth foot sock called an

udo

(plural,

udones

). The earliest mention of the garment is found in the works of the poet and epigrammatist M. Valerius Martialis, who wrote that in

udones

, the “feet will be able to take refuge in cloth made of goat’s hair.”

At that time, the

udo

fitted over the foot and shinbone. Within a period of one hundred years, Roman tailors had extended the

udo

up the leg to just above the knee, to be worn inside boots. Men who wore the stocking without boots were considered effeminate; and as these knee-length

udones

crept farther up the leg to cover the thigh, the stigma of effeminacy for men who sported them intensified.

Unfortunately, history does not record when and why the opprobrium of effeminacy attached to men wearing stockings disappeared. But it went slowly, over a period of one hundred years, and Catholic clergymen may well have been the pioneering trendsetters. The Church in the fourth century adopted above-the-knee stockings of white linen as part of a priest’s liturgical vestments. Fifth-century church mosaics display full-length stockings as the vogue among the clergy and laity of the Roman Empire.

Stockings had arrived and they were worn by men.

The popularity of form-fitting stockings grew in the eleventh century, and they became trousers known as “skin tights.” When William the Conqueror crossed the English Channel in 1066 and became the Norman king of England, he and his men introduced skin tights to the British Isles. And his son, William Rufus, wore French stocking pants (not much different in design from today’s panty hose) of such exorbitant cost that they were immortalized in a poem. By the fourteenth century, men’s tights so accurately revealed every contour of the leg, buttocks, and crotch that churchmen condemned them as immodest.

The rebellious nature of a group of fourteenth-century Venetian youths made stocking pants even more scandalous, splitting teenagers and parents into opposing camps.

A fraternity of men calling themselves La Compagna della Calza, or The Company of the Hose, wore short jackets, plumed hats, and motley skin tights, with each leg a different color. They presented public entertainments, masquerades, and concerts, and their brilliant outfits were copied by youths throughout Italy. “Young men,” complained one chronicler of the period, “are in the habit of shaving half their heads, and wearing a close-fitting cap.” And he reported that decent people found the “tight-fitting hose…to be positively immodest.” Even Geoffrey Chaucer commented critically on the attire of youth in

The Canterbury Tales

. Skin-tight, bicolored stockings

may indeed have been the first rebellious fashion statement made by teenagers.

From a fourteenth-century British illustration of an attendant handing stocking to her mistress. It’s the first pictorial evidence of a woman wearing stockings

.

The stockings discussed so far were worn by priests, warriors, and young men. When did women begin to roll on stockings?

Fashion historians are undecided. They believe that women wore stockings from about

A.D

. 600. But because long gowns concealed legs, there is scant evidence in paintings and illustrated manuscripts that, as one eighteenth-century writer expressed it, “women had legs.”

Among the earliest pictorial evidence of a woman in stockings is an illustrated 1306 British manuscript which depicts a lady in her boudoir, seated at the edge of the bed, with a servant handing her one of a pair of stockings. The other stocking is already on her leg. As for one of the earliest references to the garment in literature, Chaucer, in

The Canterbury Tales

, comments that the Wife of Bath wore stockings “of fine skarlet redde.”

Still, references to women’s stockings are extremely rare up until the sixteenth century. Female legs, though undoubtedly much admired in private, were something never to be mentioned in public. In the sixteenth century, a British gift of silk stockings for the queen of Spain was presented with full protocol to the Spanish ambassador, who drawing himself haughtily erect, proclaimed: “Take back thy stockings. And know, foolish sir, that the Queen of Spain hath no legs.”

In Queen Elizabeth’s England, women’s stockings fully enter history, and

with fashion flair. In extant texts, stockings are described as colored “scarlet crimson” and “purple,” and as “beautified with exquisite embroideries and rare incisions of the cutters art.” In 1561, the third year of her reign, Elizabeth was presented with her first pair of knitted silk stockings, which converted her to silk to the exclusion of all other stocking fabrics for the remainder of her life.

It was also during Elizabeth’s reign that the Reverend William Lee, in 1589, invented the “loome” for machine-knitting stockings. The Reverend Lee wrote that for the first time, stockings were “knit on a machine, from a single thread, in a series of connected loops.” That year, the hosiery industry began.

Nylon Stockings: May 15, 1940, United States

Because of the public-relations fanfare surrounding the debut of nylon stockings, there is no ambiguity concerning their origin. Perhaps there should have been skepticism, though, of the early claim that a pair of stockings would “last forever.”

The story begins on October 27, 1938, when the Du Pont chemical company announced the development of a new synthetic material, nylon, “passing in strength and elasticity any previously known textile fibers.” On the one hand, the breakthrough meant that the hosiery industry would no longer be periodically jeopardized by shortages of raw silk for silk stockings. But manufacturers also feared that truly indestructible stockings would quickly bankrupt the industry.

While the “miracle yarn” was displayed at the 1939 World’s Fair, women across America eagerly awaited the new nylon stockings. Test wearers were quoted as saying the garments endured “unbelievable hours of performance.”

Du Pont had shipped selected hosiery manufacturers spools of nylon yarn, which they agreed to knit according to company specifications. The mills then allotted nylon stockings to certain stores, on the promise that none be sold before “Nylon Day,” slated as May 15 of that year, 1940.

The hysteria that had been mounting across the country erupted early on that mid-May morning. Newspapers reported that no consumer item in history ever caused such nationwide pandemonium. Women queued up hours before store doors opened. Hosiery departments were stampeded for their limited stock of nylon stockings. In many stores, near riots broke out. By the close of that year, three million dozen pairs of women’s nylons had been sold—and that number could have been significantly higher if more stockings were available.

At first, the miracle nylons did appear to be virtually indestructible. Certainly that was true in comparison to delicate silk stockings. And it was also true because, due to nylons’ scarcity, women doubtless treated the one or two pairs they managed to buy with greater care than they did silk stockings.

In a remarkably short time, silk stockings were virtually obsolete. And nylon stockings became simply “nylons.” Women after all had legs, and never before in history were they so publicly displayed and admired.