Farewell (19 page)

Authors: Sergei Kostin

“Paul,” said Ferrant to introduce himself. The two men patted one another on the back, the Russian way, walked a little, and then Vetrov declared, “OK, let’s go for a drive.” They nonchalantly walked back to the Lada.

Once in the car, Ferrant started explaining his plan

5

based on the use of dead drops, as per the crash course he received from Nart in Paris. They drove to the new Lomonosov University complex on Lenin Hills. Kosygin Street bordered the university esplanade. At the level of the so-called “Stalinist style” skyscraper, there is an observatory area from which one can admire a panorama of Moscow. Below, sloping steeply to the Moscow River, a wood stretched out, crisscrossed by paths. The area was peaceful and very green. A lot of people came there to jog in the summer and ski in the winter.

The DST plan rested on this area. “Paul” would come here for his morning exercise. He would leave the car window cracked open so Vetrov could slip his documents inside.

Vetrov rejected the plan right away, not leaving Ferrant the time to explain the much more complex restitution procedure. Vladimir knew that this part of town was closely monitored by Soviet counterintelligence, who had already made several arrests of people caught red-handed exchanging documents. Independently of those facts, the place was a bad choice. On that same Kosygin Street there was a large piece of property surrounded by a blind wall. Fifteen years earlier or so, they had built dachas for Soviet leaders in this enclosed park. After the Communist bigwigs had moved out to government villages west of the capital, this infrastructure became a place reserved for distinguished guests on an official visit to Moscow. There were such visits almost constantly, and some presidents, prime ministers, or general secretaries of brother parties had reasons to fear an assassination attempt. Also, dozens of pairs of eyes were constantly monitoring any movement in the area, specifically cars with a diplomatic (CD) plate, which could well be used to transport weapons or explosives under the cover of extraterritoriality.

There were also lovers and old ladies, the “babushki,” walking in the park. According to Farewell, those babushki were the main danger. They could prove themselves to be fearsome informers, reporting on anything that seemed suspicious to them.

“Still, we need a liaison plan,” insisted Ferrant.

“No, that’s precisely the point—we don’t. We must stay away from all those techniques,” answered Vetrov. “What we must do is stay natural. Your dead drops thing, it works in the West because no one pays attention to what others are doing. Here, a guy shows up and drops a package, it’s not natural, and he would be spotted right away. What we must do is have fun, stand around, pat one another on the back, then walk to a bench while laughing. No one will find that unusual.”

Ferrant did not insist, and he accepted one by one Vetrov’s instructions. For information exchanges, “natural” simplicity was also the motto. Vetrov would hand over documents on Fridays, in the park behind the Borodino Battle Museum. At each meeting, they would set the date for the next one. If something cropped up, the third Friday of each month would be the backup meeting date.

As a good professional, Vetrov organized all the clandestine contacts on the route of his everyday comings and goings. The market once a week would be useful to have in his agenda. If he were to be tailed by KGB agents, the tailers should not wonder why he was in such place at such time. Since his wife worked at the Borodino Museum, it was normal for him to go there to pick her up after work, following his excursions in the Lada with his handling officer. Furthermore, he parked his car every evening in a covered parking garage three hundred meters away from the rendezvous spot.

The Borodino Battle Museum (circular building)…

…and the corner of Year 1812 and Denis-Davydov streets, behind the museum (see map in chapter 17). Vetrov approached Ferrant where a white Lada is parked on the sidewalk in this picture.

For his part, Ferrant did the same and worked out various ready-to-use explanations for his whereabouts. He found a shoe store, for instance, not far from the meeting point. He placed an order for very specific custom-made shoes. As a picky customer, he rejected the various models he was proposed, thus having a reason to visit the store once a week for a while. What else could be expected from a fashion-conscious Frenchman?

This first rendezvous had all the characteristics already noted by Ameil and Madeleine Ferrant, which stayed the same throughout the operation in Moscow. It was Vetrov who imposed his style of doing things. He essentially favored physical encounters over the use of dead drops, and he refused to go by traditional spying techniques. Ferrant never tried to impose anything on him. Volodia was the professional and, furthermore, he was playing on his turf, “at home.” Whether interacting with Ferrant or Ameil, the operation kept the same profile. It was a “self-operation.”

If Vetrov insisted on meeting his handlers in person, it was for a reason that had nothing to do with the operating mode of a master spy. The reason was his psychological state. Vetrov simply wanted to have the opportunity to talk with his handler, and not just to discuss the material he was transmitting. There were all those other subjects that would cross his mind, and he sure had a lot on his mind during that period. Vetrov was very frank about it during the first meeting with Ferrant. “What I want is being able to speak French with you. So, all this business with the dead drops, it’s not for me!”

As time went by, Ferrant realized that these diversions had actually become the most important aspect of their meetings. “They seemed to lift his spirits and help him momentarily get out of the schizophrenic state he was living in,” he explains. This opportunity to talk freely was a luxury Vetrov had gotten accustomed to already with Ameil. As the operation evolved, he very reluctantly gave it up.

Many weeks later, for instance, the DST was eventually able to correct a serious shortcoming the operation had in its first phase. The use of a Minox, a miniature camera, put an end to the necessity of making photocopies or taking pictures of the documents transmitted by Farewell before returning them to him. This process doubled the number of encounters and, therefore, doubled the risks. The Minox, on the other hand, allowed Vetrov to hand over films instead of documents, which minimized the risks. This technical progress and the convenience of its use was very poorly received by Vetrov since it meant cutting in half the opportunities to have conversations with his handler. Fortunately, certain technical documents required explanations, which justified additional meetings; Vetrov got the technical details over with rapidly so he could move the conversation to the difficulties in his personal life.

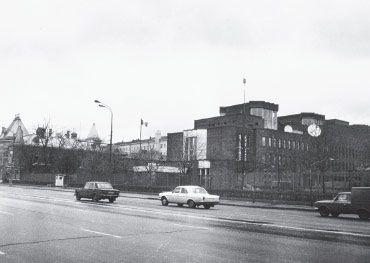

The French embassy in Moscow, where Ferrant worked. The French flag is peacefully floating in this administrative district, with the Soviet Ministry of Interior nearby. In the Western Bloc, France was a privileged partner of the Soviets.

Actually, Ferrant did not mind. Naturally curious about everything, congenial and accessible, Patrick Ferrant had the ideal psychological profile to handle a character such as Vetrov. In contrast with most Western diplomats posted in Moscow, and American diplomats more specifically, he was not living with an obsessive fear of the KGB. He favored direct contacts with the local population, in a way reminiscent of the colonial tradition of the French military. He viewed living in Moscow as a fascinating experience and a great opportunity. He made conversation with Muscovites every time he could, with the embassy guards, hitchhikers, even policemen. He knew Russian literature well, and he always had questions for the Russians he was talking to, whether about Gogol’s characters or the intrigue of a famous novel, showing his cultural attraction for this “Slavic soul” Russian people are so sensitive to. He also had a genuine affection for the people, admiring their legendary resilience. “I believe that these people deserve respect. They are so tough in the face of adversity and suffering,” he confided.

Besides Vetrov, Ferrant befriended the embassy chauffeur. The man had been the chauffeur for Marshal Rokossovsky, one of the greatest Red Army commanders during WWII. Ferrant would go with him for long drives through Moscow during which the old man recounted the time of “the Great Patriotic War.”

The House of France, the apartment building where the Ferrants lived with their five daughters. Patrick Ferrant used to stop at the sentry box to chat with the guard on duty.

His congeniality also helped place Ferrant above suspicion on the part of those who were keeping watch on him. As the person in charge of the building where the French embassy staff was living, Ferrant had a privileged relationship with the Soviet guards for any question regarding the security and tranquility of what was called the House of France. He never missed an opportunity to deepen his relations with them.

One evening, for instance, the Ferrants went out to have dinner with friends who had invited them over. The Soviet policeman scrupulously wrote down the time they left, but when they returned home, he was no longer at his post. The next day, Ferrant asked to talk to the officer on duty.

“Officer, I need to talk to you about a problem. I do not intend to file an official claim, but last night when I came back with my wife, the guard was not here. So he could not write down the time at which we returned. Which means, viewed from your perspective, my wife and I spent the night away from home, and as we speak, we are who knows where in the city.”

“I see…”

“Yes, but I do not like the idea that your superiors could believe it, do you understand?”

“I do, of course, sir. We are short on staff at the moment—it’s been difficult.”

“I understand, but I would appreciate if it does not happen again.”

Over the duration of his stay in Moscow, Ferrant never changed his attitude. Combining the natural and the casual, he always tried to establish some kind of a rapport with the person in front of him. “Coming home with my briefcase packed with the Farewell documents, I used to stop to say hello and joke with the guards. I think it was easier for them to monitor me that way. Their reports would have probably been more negative if I had been scornful or constantly suspicious of them.”