Farewell (21 page)

Authors: Sergei Kostin

Marcel Chalet was not mistaken about the impact of the file he had transmitted. When Ronald Reagan was eventually informed by his friend William Casey about the importance of the dossier, he was totally astounded. “This is the biggest fish of that kind caught since the war!” he acknowledged, even though this admission was obviously not to the advantage of American secret services.

14

This dossier, indeed, made it necessary to revise many of the certitudes held by the free world. The American president, who was no fan of communist regimes, was thus encouraged to be yet more forceful with the Eastern Bloc.

Ronald Reagan’s opinion of François Mitterrand changed radically. By sharing the information he had, the socialist president clearly demonstrated his attachment to the Western camp and its values. The obscure KGB lieutenant colonel who, at the same time, was perhaps about to drive to his dacha in a village without electricity, contributed to bringing the new French president to the fore of the international stage, making him, in no time, a major political figure of the West. Moreover, he was viewed as a man one could trust. From then on, his relations with Ronald Reagan would be frequent and friendly.

Both presidents and their respective services developed a series of measures designed to make the most, while minimizing the risks, out of the revelations made by the Russian mole in the interests of the West. They were still a long way from the massive exploitation of the information provided by Farewell. Nevertheless, already the West was forced to quietly rethink its battle order starting with the radar coverage system designed to protect the U.S. territory from a surprise attack.

Was it necessary for Mitterrand to share with another country the exploitation of the intelligence data from a source still in full operation, while every new person filled in on the case was significantly increasing the risks to “burn” the source?

Two circumstances had dictated that decision. First, one can hardly imagine a secret service hiding from the head of state pieces of information of such a capital importance, all the more when the very survival of that service was at stake.

15

Secondly, the desire of the new French president to bring a tangible proof of the fidelity of his country to the Western Bloc came, apparently, before any other consideration.

However, outside any political considerations, one can completely share the DST chief’s opinion, according to which “in any affair of this type, and whatever its scope, one is forced to evaluate the risks versus the urgency of the measures to be taken.”

16

The use of the Farewell dossier “had meaning only if the disclosed intelligence was leading to concrete measures; the arrest of the identified agents, reinforced protection of exposed targets, rethinking of compromised programs, review of security measures which appeared to be ineffective, increased surveillance of designated intelligence officers, implementation of restrictive measures aiming at crippling their activity, etc.”

17

Being in that business, Farewell had to know that political interests take precedence over the personal safety of a mole. The mole’s safety is spared only if the immediate advantages of using the provided intelligence are considered less important than the information the mole is still capable of delivering in the future. He probably was also very aware that should the information received be of a scope beyond the French interests, it would be shared with the concerned NATO country. There was nothing he could do about that. Those were the rules of the game, and by choosing to take the plunge, he was giving himself body and soul to his new masters.

As those important international events were developing, Vetrov was spending his last summer at his dacha in Kresty. During the period when the heads of state of two great powers in the West were pondering over his dossier, the only president he was meeting with regularly was Victor Kalinin, who presided over the local kolkhoz.

Vladimir would get up early, grab two buckets, and walk to the river Tvertsa to get water. After breakfast, equipped with a hammer and a saw, he would work all day till night. Then, either his neighbor Maria Makarovna came to visit, with her endless supply of stories, or Zhenia came, the simpleton from the neighboring village of Telitsyno, who grazed the kolkhoz herd behind their house. From time to time, Vladimir and Svetlana socialized with the Rogatins around a bottle or two, at the table they had in the yard.

The Vetrovs were in great need of others’ company. Svetlana and Vladimir were not on speaking terms, uttering just a few words when absolutely necessary. Vetrov spent his time with Vladik. They had undertaken the construction of a terrace. As he was nailing a board down, he told his son an important secret.

“You know, I won’t be coming back here. But the veranda will be finished.”

Vladik put the hammer down and looked at him inquiringly.

“I can’t take it anymore; I am leaving,” continued Vladimir.

His son, who knew about Vetrov’s mistress, was nevertheless stunned by the news.

“To go live with…with her?”

“Yes.”

Realizing the distraught look on his son’s face, Vetrov hastened to reassure him. “It won’t change a thing between us, you’ll see! You’re my son; I’ll help you and all. But I have to go away.”

Yet, two days later, he stopped by the Rogatins’ “ranch.” As an experienced handyman, he inspected the latest improvements they’d made to their house. The basement was of special interest to him. His was three meters deep, and he was wondering what he could do with it. They also needed to work on the second floor, which could make a very romantic attic room.

“I still have two more years to go,” said Vetrov. “Then, I will retire and come live here. It’s going to be great!”

As he was two days earlier with his son, he seemed sincere. But if he was talking nonsense, it was apparently because he did not know what he was going to do.

One evening, he came alone to visit the Rogatins. He was bored; it had been raining nonstop for two days. Since there was light inside, he knocked at the window, and Galina rushed up to open the door. That summer, the Rogatins had friends over, a couple, Alina and Nikolai Bocharov. They were eating, and Vladimir gladly accepted their invitation to join them.

Alina Ivanovna’s account has the value of a snapshot. Compared to photography requiring posing by the subject, or compared to painted portraits, it is the first impression conveyed by a snapshot which is of interest. This first impression is not affected by the past actions of a familiar individual, nor by his or her future behavior. All the same, as for any testimony, some reservation is necessary. The impression is also dependent on the medium of the print. Director of a fashion atelier, like her friend Galina, Alina was a fairly simple woman. Without questioning her objectivity, it is important to understand that, to her, Vetrov was somehow from another planet.

Fifteen years later, Alina remembered vividly this handsome man who charmed her immediately. He had a strong build, a pleasant voice, was always elegantly dressed, even in this village in the middle of nowhere, and his manners and way of speaking were those of a well-educated man. Vladimir had what she would call the “polish” of somebody who had lived in the West.

Alina was, first of all, struck by the candor of this late guest, even though she knew he was a KGB officer. During a general conversation where the guests were jumping from one subject to another, Vetrov revealed that, supposedly, Lenin died from syphilis, and he made no bones about criticizing Andropov, the big boss of the KGB. In one hour, he said more than would have been needed to put him away for “anti-Soviet propaganda.” Maybe because he realized that he was talking too freely, he advised the people at the table to never mention such topics in Moscow, where all it took was to run an additional wire to the lamppost across the street to tap any “seditious” conversations.

Progressively, Alina realized that Vladimir was not his normal self. He seemed under the weight of a tremendous emotional burden. This uneasy feeling got worse once they were alone. It was getting late, and Galina invited Vetrov to stay overnight. Then, everybody went to bed, but Vladimir and Alina stayed behind to chat a little longer.

Clearly, Vetrov needed to talk. Alina remembers him sitting on a wooden bench, between two dogs, the Rogatins’ boxer and the Bocharovs’ poodle. As he was petting them, he told her about Ludmila, with whom he was madly in love. This even surprised Alina. Who could this woman be who managed to ensnare a handsome, intelligent man, with such a beautiful spouse like Svetlana? In fact, instead of making him happy, this love affair seemed to be a permanent source of stress. At some point, Vladimir broke into tears in Alina’s presence. She was, after all, not a close friend of his. This struck her all the more because they had been drinking only tea the entire evening. More and more, she thought there was something wrong with him psychologically.

A few days later, she had confirmation that Vetrov did not know what he was doing. The elegant man she had seen the other night showed up with only the lining of a shapka (a Russian fur hat) on his head. This was really weird. Even peasants, who had no problem wearing their grandfathers’ grimy caps, would not have worn this thing. Alexei Rogatin vaguely suggested that it could be nice to grill meat on skewers outside. Vetrov left on the spot, soon to return with a live sheep he had bought in the village. A neighbor killed it and cut it up, but the urbanites did not feel like eating an animal that one hour earlier was bleating outside the window. Vetrov did not want it either, and he took the meat away, packed in a bucket. Obviously, the man was jumping on any opportunity that presented itself to be entertained and to keep his anxiety at bay.

On July 31, Alexei Rogatin celebrated his fiftieth birthday. All their friends came from Moscow to stay with them in the country. There must have been half a dozen cars parked in front of their izba. Like kids, the men played soccer, cheered on by their wives, and by the people of Telitsyno who, although separated from the group by the river, were watching from their porches. The Vetrovs were invited, but they showed up only at the end of a sumptuous meal, and not together. Svetlana arrived first, on a neighbor’s scooter, holding both of their dogs in her arms. Vladimir appeared shortly after, staggering along, already seriously drunk.

The next day, when the hosts and their guests were about to leave to go back to Moscow, he reappeared just by himself. He wanted to take advantage of the coach, which was taking most of the group back to town.

“Galya, I am at the end of my rope,” he said, taking the lady of the house aside.

Galina knew about his torments.

“What do you want me to do? I can give you a drink if you have a hangover. But for the rest, it is for you to solve your problems with women.”

“I know. I just need somebody to talk to.”

“OK, come see us in Moscow, then.”

Vetrov seemed relieved.

“Thanks. Didn’t you mention a drink?”

Yet, he kept whining the whole trip. Every once in a while, Vasily, one of the guests, also a former KGB operative, who was dozing off as a consequence of the libations that took place the day before, would lift his head and mumble somberly, “Stop the babbling!”

This reprieve on the banks of the Tvertsa ended with Vetrov’s vacation. In the last days of August, Vladimir came back to Moscow and his problems. They did not get solved on their own while he was away. Ludmila requested that he leave Svetlana. And his mortal game with the French was about to resume.

His journey with no compass was entering its decisive stage.

“Touring” Moscow

By the end of July, Patrick Ferrant was back in Moscow. During their first post-vacation meeting, the two officers defined their method of contact. At each rendezvous, they confirmed the date of the next meeting, a date that might change if circumstances demanded it.

Actually, the frequency of their meetings depended on the files that landed on Vetrov’s desk at Directorate T. Farewell could tell Ferrant in advance what was in the pipeline, and thus plan their meetings more accurately. As a general rule, the procedure was always the same: the documents received by Ferrant were copied, then returned without delay. Vetrov’s worst fear was that his handler might not be able to return the documents on time, and Ferrant remembers that logistics were not always optimum to fulfill that requirement.

On August 25, for instance, Vetrov brought a cardboard box filled with documents to be returned the next morning at nine without fail. But at that time of the year, the embassy was closed for a couple of weeks, so it was impossible to use the photocopier without attracting the KGB’s attention. “OK, I’ll take it,” said the French officer without flinching. He then went directly to the military mission and gathered all the rolls of film he could find, then bought a few more and went home with the box of documents. “I got everything together and, that evening with my wife in the apartment hallway, using a bedside lamp and my Canon camera, we shot maybe twenty 24x36 rolls of film. My wife turned the pages; she had loud music on because we did not know where the hidden mics were, and you could hear the clicking noise from the camera.”

In the fall of 1981, Vetrov met seven times with Ferrant, on the first and the third Friday of each month; September 4 and 18, October 2 and 16, November 6 and 20, and December 4.

1

The time was usually seven p.m., and the place almost always the same, with few variations, behind the Borodino Battle Museum.

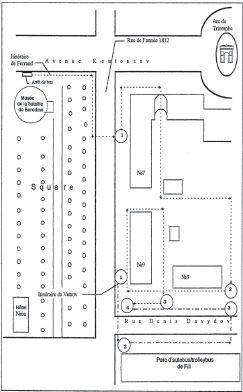

A career soldier, “Paul” was very punctual. At seven o’clock sharp, Vetrov could spot his tall figure as he turned into Year 1812 Street. Ferrant came by bus or trolley. One day, he told his mole that he had parked his car in front of the Arbat restaurant on Kalinin Avenue (from which Kutuzov Avenue runs on). Depending on the season, “Paul” was wearing a long, pistachio-green raincoat or a parka of the same color with zipped pockets, over brown corduroys. On cold days, he wore a gray wool hat. Before meeting face to face, the two men followed an intricate security route to make sure neither of them was tailed (

see Figure 3

).

2

Despite the many advantages offered by the operation using “Paul,” the DST still had some reservations about its mole’s sincerity. You cannot change your own character; French counterintelligence was so experienced in the tricks of the trade, it saw double-dealings and traps everywhere.

Thus, on their second meeting in September, Ferrant conveyed regards to Farewell from a “Monsieur Maurice.” From that conversation, Vetrov thought the man was one of Paul’s bosses supervising the operation from Paris. Since Patrick Ferrant’s code name started with the same letter as his first name, one could assume by analogy that “Maurice” was no other than Marcel Chalet.

Figure 3. Security routes followed by Ferrant and Vetrov, respectively. 1–3: visual contacts; 4: meeting point.

The message started with kind words. “Maurice” was very concerned about Farewell’s safety, and he was asking him to take all the necessary precautions. And by the way, could Farewell take that opportunity to tell him what prompted him to contact the French secret service and provide them with confidential information?

This was not an issue for Vetrov. On the next meeting, Vladimir handed Ferrant the following note, in broken French:

3

Dear Maurice,

Thank you for worrying about my safety. I will do everything I can in this regard.

You are asking why I took this step. I could explain as follows. Sure, I like France very much, a country that marked my soul deeply, but apart from this, I detest and am appalled by the regime in place in our country. This totalitarian order crushes individuals and promotes discord between people. There is nothing good in our life; in short it’s rotten through and through.

Vetrov’s letter had the expected effect; the French never questioned his sincerity again.

Ferrant often asked him precise questions. Sometimes, Vetrov could answer immediately. If not, he came to the next meeting with a sheet of paper, with the answers he had typed in his office. Usually, it was just one page handed over to “Paul” in the evening. Longer lists with the names and addresses of Directorate T officers and contact information for KGB agents infiltrated in the West were handwritten.

4

In September, Ferrant also brought Vetrov the “famous” Minox the CIA had given Raymond Nart. This first camera was fairly rudimentary; a roll yielded about sixty snapshots, and a full page required two photos. Very soon it was replaced with a more sophisticated and smaller camera, thumb-wide, easily hidden in the palm of one’s hand; two cameras were delivered to Vetrov. Nart had sent two of his men to the CIA to learn how to use this “little marvel of technology.”

5

Then they trained Ferrant during one of his trips to Paris, and Ferrant trained Vetrov in his Lada. To ensure good focus, the camera had a string with a needle at the end; when the needle was resting flat on the document, the camera was at the right distance to obtain a good picture. Also, the needle could provide a good alibi. If a coworker was to suddenly step into his office, Vetrov had only to close his hand to hide the camera, and pretend he was sewing a button back on his jacket. The rolls looked more like small audio tapes, and they advanced automatically as pictures were taken. A roll could yield up to 160 snapshots. From that moment on, Vetrov would deliver films in plastic bags to the Frenchman, often ten or twenty at a time. This gives a better idea of Vetrov’s very real autonomy. It also shows the flexibility introduced into the process of setting dates for the meetings. Up to that point, it was imperative that documents delivered on Fridays be returned over the weekend. With the miniature camera, rendezvous could take place any day of the week, the date having been set during the previous meeting.

The main consequence of using a camera is the drastic reduction of the physical contacts. As already mentioned, it was precisely for that reason that Vetrov did not welcome this technological advance with much enthusiasm. His considerations were none of the DST’s concern; all that mattered was the necessity to reduce the number of meetings. Nart had explicitly insisted on that point with Ferrant:

“We’ve got to diminish the frequency of the contacts. No more trailing around like this in Moscow, with briefcases full of documents. With the camera, we should be able to limit the rendezvous to six or seven a year.”

“Alright, but you must know that Vetrov needs those contacts—they are one of his main motivations,” replied Ferrant.

6

As secondary as it may seem within the overall context of the operation, the opportunity provided to Vetrov to speak freely during the meetings turned out to play a crucial role in stabilizing his precarious psychological state. Besides the normal pressure of the job, it was the weight of the contradictions Vetrov had to manage every day that threatened this equilibrium.

We know that Vetrov was an extroverted and congenial individual, inconsistent with the constant suspicion required by the world of espionage. He also had more and more difficulty coping with the general climate of lies and hypocrisy in which he was living. In his professional life, the brilliant agent he had been at one point came up against Brezhnevian favoritism in the seventies, when belief in communist ideals was reduced to a hypocritical façade necessary to get ahead in one’s career. Life in a communist regime also made it necessary to pretend you believed in the official ideology, promising a radiant future to triumphant socialism, a picture that was far from the harsh reality of daily life. This mild schizophrenia, endured by the majority of the population, was exacerbated in former KGB residents like Vetrov who had lived abroad and knew, but could not say, that life in Paris did not match the description given by official propaganda. His conversations with Alina Bocharova, when they met in the countryside, showed how difficult it was for Vetrov to remain politically correct.

The situation was no better in his private life. His marriage survived only for their son’s sake. Their life as a couple had only the appearance of normality. Svetlana and Vladimir led separate lives, each with their own love affairs.

Whether to appear faithful to a regime he hated, or to keep a shattered family life together, Vetrov was forced to live a double life in contradiction with his personality.

Against this backdrop, it is easy to understand the liberation he felt in his meetings with Ferrant. In them, Vetrov found the simplicity and frankness he needed. They did him a lot of good, sweeping away the unspoken resentments of his daily life. Having crossed the Rubicon of illegality, Vetrov certainly intended to enjoy his freedom of speech to its fullest.

What did the two men talk about during their long drives through Moscow?

“Not that much about the operation. We talked mostly about his private life, about very personal details even, in veiled terms, but still…” remembers Ferrant. As he did with the Rogatins, Vetrov easily confided about the difficulties with Ludmila to his friends. With his French handler, he went a step further in sharing private details of his life. “I had become his analyst, or his sex therapist, rather. He was looking for explanations on many subjects, including the fact that ‘he could not do it anymore’ with his wife, although he still loved her. He told me, on the other hand, that he was crazy about Ludmila, but this attraction seemed to annoy him more than anything else.”

This latter point preoccupied Vetrov more than the former. “I sensed, early in the game, that his mistress had become a source of trouble to him,” confirmed Ferrant without knowing exactly how Vetrov’s relationship with Ludmila was evolving.

For the accidental “spychologist” the French officer had become, the main concern was to help Vetrov calm down, to bring him as much stability as possible so the operation would not suffer from Vetrov’s emotional state. Ferrant would reassure him as much as he could, confirming that “it was normal,” past a certain age, not to have the same vigor as during one’s prime, and also to be tempted to go see if the grass was greener on the other side of the fence. Those platitudes made Vetrov feel better about himself, now belonging to “normal” behavior patterns, the opposite of the inner turmoil he was experiencing.

However, according to Ferrant, happiness for Vetrov was to be found in simple things. Their conversations moved naturally to their respective country houses. The Frenchman had a secondary home in the French Pyrenees. His dacha, the improvements he was planning to make, and how he would quietly retire there were Vetrov’s favorite topics of conversation.

The many descriptions Vetrov gave of the Russian countryside helped Ferrant understand how deep, if paradoxical, his attachment to the land was, even for a defector of his caliber. “A visceral patriotism I encountered only among the Russian people.” Vetrov might not have had many illusions left about the regime he served, but he showed a deep, passionate attachment to his native soil. As if intertwined, his son Vladik was also a recurring topic. Vetrov enjoyed talking about him, imagining his future or describing his personality.

As we will see later, those are the two main points that explained, in the DST’s opinion, why Vetrov steadfastly refused to plan his exfiltration or even simply talk about the possibility of going abroad.

At this point, it would be tempting to point to the many contradictions of a man who was cheating on the woman he loved and betraying the country he cherished. In the heat of the discussions with Ferrant, though, Vetrov was still able to manage those contradictions.

During their Muscovite journeys, Vetrov never abandoned his good humor and remained self-confident. In the most relaxed fashion, as he drove his handler around, he gave him a tour of secret Moscow, pointing out to Ferrant the most sensitive organizations in the city. One day, showing his KGB card to the guard on duty, he drove, with his passenger on board, into the yard of a missile manufacturing plant.

7

Though spectacular as those escapades were, Ferrant never had the feeling that Vetrov was being that reckless because he seemed totally in control of the situation at all times.

As far as security procedures were concerned, Vetrov always showed the same self-assured nonchalance as for the other aspects of the handling.