Farewell (23 page)

Authors: Sergei Kostin

The Lull Before the Storm

Russians who socialized with Vetrov during the fall of 1981 noted two major personality traits. One was perfectly adapted to the never-ending discussions with Ferrant, and the other was at odds with his profession as an intelligence officer and with his mole status: he talked too much, and he drank too much.

Vetrov had no inhibition discussing his private life, particularly his difficulties with Svetlana and Ludmila. From his taste for dirty jokes, his colleagues had guessed the sexual issues he confided to Ferrant. “Those who do don’t talk, those who talk don’t do,” would have said Lao Tzu. Vladimir could be especially indiscreet when he indulged his favorite pastime—drinking. He got into the habit of visiting Galina Rogatina, not so much to share a drink or two, but to simply chat because Galina was an intelligent and perceptive woman.

She had gone through ups and downs in her life. She had spent almost a year in jail after being wrongly accused; it was an extremely trying experience, but she had no regrets. Rather than judging others, she tended to be understanding and forgiving. To her own amazement, those qualities made her Vetrov’s confidant at a time when he was going through great moral solitude.

Since the summer, his relationship with Ludmila had turned sour. Instead of dreaming of living with her, he thought only about getting rid of her. He told anyone who would listen that Ludmila would not let him go. He was in a quandary. As could be expected from a good Soviet citizen, Galina gave him a piece of advice.

“You are working together, right? Go talk to the Party organization, so they can tell her to leave you alone!”

One must have lived under the Soviets to understand the meaning of such a suggestion. The Communist Party, society’s vanguard, was in charge of the morality of its members. Adultery was considered a clear proof of depravity, for men and women alike. For a KGB officer, it was a serious professional mistake. Vetrov’s affair with Ludmila was an open secret in the service, but as long as nobody complained about it, theoretically his superiors ignored the situation. Vetrov was not thrilled by Galina’s advice since officially approaching the Party Committee would have launched a bureaucratic process difficult to hush up. However, the suggestion would turn out to be very useful. Stereotyped behavior made his PGU colleagues and superiors’ reactions predictable, which would play a significant role in what followed.

Despite those difficulties, Vetrov’s life was not all that bad. While money was never mentioned when handled by Ameil, later on he started receiving a small allowance for his daily expenses. He seemed to appreciate the advantages provided by his new situation. From a few remarks he made, one was led to believe that the amounts he received from “Paul” were significant.

1

What follows is telling.

Recall, the building where the Rogatins lived housed an antique shop on the ground floor. The Vetrovs were regulars and knew the store director well as he granted them easy terms. They would make sure to be among the first customers to go in at opening time on Fridays, the day of the week when new acquisitions were put up for sale. This episode also tells us that the couple still spent some time together, since one day in the fall of 1981 they went to the antique store together.

Galina remembers it as if it were yesterday: dressed in an elegant black coat, Vetrov, all excited, rang at the Rogatins’ door.

“An old painting downstairs caught Sveta’s fancy. Could I borrow money from you?” he said.

Such a request was nothing out of the ordinary. Russians borrow and lend easily between themselves, even large amounts, without asking for a receipt.

“How much do you need?”

“Seventeen thousand.”

Alexei could not believe his ears. He was making two hundred forty rubles a month as the chauffeur for the Luxemburg ambassador.

“You’re out of your mind! Where do you expect me to find that kind of money?”

“Come on…you could ask a neighbor or a friend.”

“If it were just one or two thousand rubles, that would be no problem, but seventeen thousand, you must be kidding! I’ve never handled that much money in my entire life!”

Then, Vetrov said something Alexei did not pay attention to at the time, but later he would think about it again and again.

“Try anyway! I am supposed to receive money from Leningrad in a few days. I’ll have enough to lend some myself.”

To understand the Rogatins’ amazement, consider that under a communist regime, especially in its Soviet version, everyone had a fixed source of revenue. This could be of diverse origin—salary, retirement pension, student aid—but always paid by the State. Extra earnings were officially prohibited and poorly thought of. An officer, by definition, could not make money on the side.

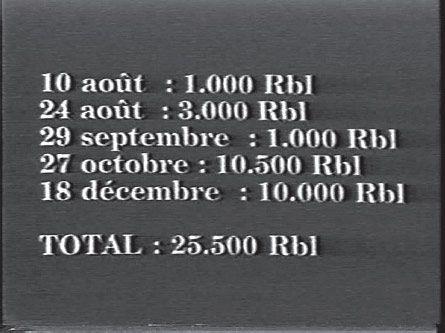

Today, through access to documentation on the Farewell affair compiled in-house by the DST, it is possible to reveal the exact amount of the financial compensation Vetrov received for his collaboration: 25,500 rubles (

see Figure 4

). Overall, although such an amount of money may seem minimal compared to the compensations received by moles paid by the CIA or the KGB, it is nevertheless impressive for an ordinary Soviet citizen. It was the equivalent of eighteen years of an engineer’s, doctor’s, or teacher’s salary, and more than four years of income for a KGB officer such as Vetrov. Put another way, with that much money, Vetrov could have bought five Ladas like his.

The fact that he could take her to a fancy restaurant every once in a while did not go unnoticed with Ludmila either. Not only was an officer not supposed to have money “on the side,” but as a married man he was also expected to give his entire income to his family. A married woman herself, Ludmila asked him about it once. Vetrov told her some vague story about a friend in Leningrad he had supposedly helped out of a bad situation in the past. As a sign of his gratitude, the friend was sending him money regularly. Ludmila suspected some kind of scheming and so did not press for details.

Figure 4. Farewell’s compensation. Detail of a DST archive film.

Up to this point, nothing indicated that this illicit income had anything to do with the sale of KGB secrets, which explains why the Rogatins and Ludmila never had any suspicion in this direction. They all knew that Svetlana, being a fine art collector, acquired or sold expensive objects, and not always going through official channels. The next episode has a more alarming ring to it.

One day at the Rogatins’, after a meal generously washed down with wine and vodka, the men started talking cars. In those days, an ordinary Soviet citizen had four brands to choose from—Volga, Lada (Zhigouli), Moskvich, or Zaporozhets

2

—all of them primitive compared to Western cars. Alexei and Vladimir, however, drove many cars in their lives and had a broader range of references for comparison.

In the heat of the discussion, Vetrov suddenly said, “I can have any car I want.”

At Alexei’s incredulous expression, he added, “All I have to do is ask the French. They’ll get me the brand I want.”

The Rogatins did not react to this probable drunkard’s boasting. But why the French? Well, after all, Vetrov was a KGB member. Who knows what type of operation he was involved in.

Afterwards, Svetlana also remembered something else her husband said to her on a “truce” day: “I’ll buy you a magnificent house not far from Moscow.”

However, even in those days, dachas close to the capital cost a fortune.

Regarding his alleged wealth, Vetrov was even more explicit with his son. What was the basis of this? It remains one of the many unsolved mysteries of the Farewell case.

Vetrov’s portrait at the time needs another brushstroke to be more complete. Vladimir was talkative to be sure, but when comparing the various statements attributed to him during interviews with close relations, one sees a web of lies and contradictions.

During the rare lulls in their relationship, Vladimir vowed eternal love to Svetlana and assured her that no other women ever counted in his life. In the middle of his tumultuous love life (around November 1981), he said the same thing to the Rogatins; he wanted to live with Svetlana, but Ludmila was clinging to him. To Ludmila he could declare on that same day that she was the only woman he loved, and that the atmosphere at home had become unbearable. He also told her that he hated his mother-in-law, who lived with them, and above all, he hated Svetlana. He also let it be known at work. But Vetrov was not consistent in his maliciousness. In the morning he confided to Galina Rogatina, his only true friend, about his desire to get rid of Ludmila. Two hours later, he rushed to see his mistress and make a date with her, pretending he had very important things to tell her. In fact, all he had to say was to drag the Rogatins’ name through the mud.

To listen to Vetrov, the entire world was against him.

He had another reason to feel unhappy.

In a matter of a few months, Vetrov went from being a bureaucrat of no significance to being a hero. At least this is the image he must have had of himself. He wanted to be admired, and he needed an audience. In the eyes of others, though, he was still the same man. This is why Vetrov was so eager to meet physically with his handler, who was the only person who understood the significance of his actions and the huge risks he was taking.

This desire to play the hero in front of his only witness might have been what motivated Vetrov to drive into the yard of a missile manufacturing plant with a French intelligence officer as his passenger; this makes that episode plausible.

Since he had started using the miniature camera, Vetrov met with Ferrant only once or twice a month, and at the DST’s request the rendezvous became even less frequent starting in early 1982. This was a problem, considering how much Vetrov needed to talk to someone when the tension in his life was becoming unbearable.

He must have had an idea that Svetlana would not find it acceptable that the father of her child, and her husband, was a traitor. She would have thought that the revelation of his spying activities, the trial, and the ensuing shame could destroy Vladik. It was, therefore, not a bright idea to try reconciliation with his wife by telling her that he had become a mole.

Nor could Vetrov confide in Ludmila; infatuated though he was with her at the beginning of their affair, he would have been out of his mind to make the slightest allusion to his dangerous undertaking in his mistress’s presence. Not only did he know in his heart that betraying one’s country would not be very attractive to the woman he had just seduced and wanted to keep, he also knew of a more imperative reason not to share his secret. Even though Ludmila was not under oath at work, she had signed, as every KGB employee had to, an agreement making it mandatory for her to report without delay any colleague’s suspicious or odd behavior. Failure to report any fact that might help discover a mole within the organization would have made her an accomplice, which would have put her on trial along with the mole.

In the end, there was only one person in the whole world Vetrov could open his soul to: his son.

Vladik

Sergei Kostin met Vladik at the same time he met Svetlana. He was a quiet young man, looking younger than thirty-three. Handsome, fairly tall, with regular features and soft dark eyes, he was rather unassuming, courteous, and kindly. This was no longer the cute little boy from the family slides, with his carefully cut bangs, dressed like a little English lord, who refused to talk to people other than his parents. It is difficult to imagine what went through his mind as the son of a spy, and what had been the impact on his social life. But today, the overall impression given by Vladik is still one of a preppy kid from “a good family,” who knows he is loved dearly and who tries to be a good boy.

The impression of dealing with a child was reinforced after an evening spent talking about his father. Vladik merely quoted facts, words, and remarks he remembered. Sergei Kostin did not sense any distance on Vladik’s part from what he was recounting. Himself the father of a ten-year-old boy, Vladik seemed to find it natural that his father, by sharing his secrets, made him carry a heavy moral burden. Furthermore, he made him his accomplice in an espionage affair! Vladik gave no sign of having changed his views as he recounted their intention to “be tough” with Ludmila, nor did he make comments such as “I was really dumb when I was eighteen” in the course of the conversation. None of that! His voice was calm, and only his stutter, more frequent than usual, indicated he was tense. Had he learned to control himself from the great ordeals he underwent, having to cope with shame and humiliation? Had he decided to deliver only bare facts, with no emotions and no interpretations, to let his interviewer form an opinion for himself? Hard to say, but this made his testimony even more credible.

From his son’s earliest days, Vladimir acted as a real “mother hen” with him. Much more than Svetlana, he surrounded him with tender loving care and catered to Vladik’s every whim. He encouraged him to practice a sport by jogging with him, and he helped him with his homework. Vladik was a student in a secondary school specializing in mathematics and physics. A good mathematician himself, Vetrov would get angry when his son came back home with grades that were good instead of excellent.

Every once in a while they would fall out, and Svetlana would reconcile them. According to her recollection, she was stricter with their child and always let him know when he was wrong. As for Vladimir, he had a tendency to make excuses for him.

As Vladik was growing up, Vetrov told him more and more about his job. Before his return from Canada, Vladik thought his dad was employed by the Ministry of Foreign Trade. Once he learned the truth, he started saying to his schoolmates that his father worked for the Ministry of Radio Industry. Close enough, considering that Vetrov’s field of expertise was in missiles, aerospace, telecommunication, and so forth. He would regularly show his son advertising brochures from major Western weapon manufacturers. He gave him folders with pictures of airplanes or tanks on the cover.

At first, Vetrov imagined his son following in his steps, starting with acceptance in the ciphering department of the KGB school he had attended. Then, as his views of the organization changed, he leaned more toward a civilian career.

The Vetrovs tried to have Vladik admitted to the Economics Department of Lomonosov University. Knowledge by itself was already no longer sufficient for acceptance to one of the most prestigious academic institutions in the country. Out of fifty openings, only two or three would go to whiz kids with no sponsors. The rest was up for grabs and had to be fought for through influential people, friends, and money. Having placed too much confidence in a friend of a friend who had a key position in the faculty, the Vetrovs lost the battle. They would later learn that the man hated the KGB.

Vladik went to work as a lab assistant at the Moscow Institute of Fine Chemical Technology (MITKhT), curiously also named Lomonosov. The following summer, things got serious because, if he failed his exams, Vladik would be conscripted into the army. This was no joke in the middle of the war in Afghanistan. After a year working at the MITKhT, Vladik knew a lot of people there. So why take risks? He thus passed the competitive entrance exam and became a student in this modest institute most Muscovites had never heard about.

In the fall of 1980, Vladik started his first year. Having a trusting relationship with his father, he was not surprised when Vladimir mentioned his collaboration with the French even before it started; in all likelihood, it was the beginning of March 1981, following Ameil’s initial phone call.

Why did Vladik not attempt to talk his father out of his plan?

“It would have been of no use,” he answered. “My father was so stubborn. Maybe I was not that opposed to the idea myself.”

But Vladik wanted to know what prompted his father’s decision. Vetrov mentioned only his grievances against the KGB. In Vladik’s opinion, too, the motivation was not a hatred of the regime. The only thing his father hated was the service, its general atmosphere and the intrigues.

Vladik waited, impatient and anxious, for his dad to come home after the first rendezvous with Ameil. Unfortunately, he could not have the conversation he was hoping for because Vetrov came home drunk. We know that the Thomson-CSF representative had never been his drinking companion, so Vladimir, in all likelihood, went for a drink after the meeting, alone.

He made sure not to tell his son about the details of the operation. After Ameil, all Vladik knew was that his dad was seeing a certain “Paul.” One day, as they were driving on Year 1812 Street, Vetrov told his son that once he met the Frenchman in that same area.

One evening in November 1981, if Vladik’s memory served him correctly, his father came home dead drunk. He started telling him he was back from the French embassy where a small banquet had been organized in his honor. From what Vladik gathered, he had been awarded a French decoration. He is not completely sure; his dad could hardly stand. Vladik is certain, however, that he heard him say, “She is the only one who does not appreciate me; the French think the world of me.”

“She” being Svetlana, clearly.

The next day, Vladik asked him questions about the visit to the embassy. His father explained that “Paul” took him in the trunk of his car, going in and going out.

The story is not believable, and it was never confirmed by any French source. The desire to flatter its mole’s ego, provided there was such a desire on the part of the DST, did not justify taking such a risk. Who else could have been invited to that banquet? It would have resulted in a dramatic increase of the number of individuals informed of the operation; the banquet story could only be pure invention. It was well deserved in Vetrov’s mind that a hero like himself would receive such conspicuous marks of appreciation. For lack of such gratitude, he invented it for his son’s benefit.

Vladik readily admits that his dad was quick to get carried away. When a new idea caught his imagination, he could nurture it for weeks. He would eventually believe in his dreams. Then, when his latest castle in the air crumbled, he forgot about it just like that.

For instance, for years he talked about moving permanently to the countryside for his retirement. He would get hired to drive a tractor or a harvester, spending the rest of his life in the great outdoors surrounded by fields and meadows. He toyed with this idea until the summer of 1980. Then, having become a French mole, he abandoned his pastoral dream for a much more extravagant project.

Almost every evening Vladik accompanied his father to park their car on Promyshlenny Passage, a small street located behind the Borodino Battle Museum. There stood two long, three-level buildings, each sheltering hundreds of vehicles, mechanical repair shops, carwash facilities, and so forth. The Vetrovs left their car in their parking spot and walked back home. This was the moment of the day when father and son could spend forty-five minutes together and discuss their problems. It was during one of those “parking trips,” around November 1981, that Vetrov shared his new plan with his son. He proposed fleeing to the West, just the two of them. His French friends would arrange their passage to the embassy by putting them in the trunk of a car. From there, everything would be easy.

As fantastic as the story may seem technically, Raymond Nart confirmed that there was a plan along those lines. The DST deputy director was even keeping, “at their disposal,” two false French passports. Unfortunately, like most escape plans devised by the DST, this plan remained just an idea.

From day to day, Vetrov embellished his plan with new details. They would live in Canada or in the United States; Vladik would go to college. They would not be in need of anything. “I have enough money to buy an island,” declared Vetrov.

While being aware of the dreaming nature of his father, Vladik believed that the plan was very serious. Maybe he too wanted to believe in it. On the other hand, the young man was hesitant because he did not want to abandon his mother. He had said so to Vetrov. His father nonetheless kept discussing the plan.

Vladik clarified that this was not an escape plan for when the moment would be right, in six months or a year; this was a plan for an imminent move. Did Vetrov understand that the game had become too dangerous to last much longer? Further, and Vladik is adamant on this point, Vetrov never planned to settle in France. This leads to two conclusions. It validates the assumption that cultural affinities with France were not part of Farewell’s decision to collaborate with the DST. Being in Moscow, he thought he was taking less of a risk with the DST. Once in the West, however, he would be safer, and certainly more pampered, as a Langley resident.

The technical aspects of the escape were nevertheless problematic. Once in the French embassy, “it is easy” had declared Vetrov. Raymond Nart has confirmed that the DST had contemplated an exfiltration via the French embassy. An operation “à la Gordievsky,” which in theory should not have posed too many problems.

1

In reality, that was when true problems would have started.

Nearly all of KGB or GRU renegades defected while in the West. Soviet counterintelligence knew of only two successful escapes from the Soviet Union by KGB moles working for Western intelligence. One was the exfiltration of Victor Sheymov, with his wife and young daughter, by the CIA in 1980; the other was the case of Oleg Gordievsky, exfiltrated in 1985 by MI6 (British intelligence). It is unlikely that the moles escaped through the embassy of the country they worked for. Let us examine the most optimistic hypothesis. If we assume that Vetrov and his son could get passage to the French embassy hidden in the trunk of a car, it would mean informing other embassy personnel beyond Ferrant. This could involve four or five individuals: the ambassador, the military attaché, the head of security, and one or two guards. The risk of leaking information would then be increased significantly, even if they all maintained absolute silence and managed to provide a space for the Vetrovs inside the embassy totally sheltered from the KGB’s ears and eyes, making the Vetrovs’ presence unnoticeable, assuming that the PGU ignored that its missing officer was now willingly in French territory in the heart of Moscow. Lastly, let us believe that the fugitives would stay in the embassy for the shortest time possible since the risk of being spotted increases with every day. Even if all those favorable conditions were met, the hardest part of the operation would be yet to come.

A man cannot be shipped like a parcel in the diplomatic pouch. An actual failed exfiltration attempted in the seventies had the following plan. A Westerner with a physical resemblance to the individual being exfiltrated, and made up to look even more like him, arrived in Moscow on a business trip. The mole was expected to cross the border back to the West carrying the Westerner’s passport. With the mole safely on the other side, the Westerner could have reported a stolen passport and left the Soviet Union with a temporary passport. The plan seemed reasonable enough, especially considering the fact that the mole was fluent in the language of the country he was supposed to be from (which would not have been Vladik’s case). Unfortunately, because of edginess or some kind of typically Soviet behavior on his part, the mole attracted the attention of the customs officials and was arrested at the airport.

One must admit that such an operation is tricky, even for a service that would have thought out all the details of the exfiltration well in advance. Was it one of the many escape plans Ferrant talked about that led Vetrov’s wild imagination to the craziest scenarios? It is likely, since the DST had not finalized any emergency procedure to be implemented in Moscow. If so, a more reasonable man would not seriously contemplate fleeing to the West via the French embassy.

Why did he? Why did he keep entertaining ideas he must have known to be totally unworkable? All the indications lead to the belief that, by then, he had become more and more delusional.

Vetrov would not have the opportunity to see for himself how illusory his escape plan was. The tensions in his life were getting worse, and the safety valve Vladik represented was no longer sufficient. Vladimir was walking through a minefield.

In early February 1982, Vetrov mentioned to his son that Ludmila had given him an ultimatum until February 23. His mistress, he said, stole secret documents from his jacket. Having understood he was collaborating with a foreign country, she supposedly was blackmailing him. In Vladik’s opinion, Ludmila did not care about his father anymore. She simply wanted to benefit from the situation to extort money from him. Vetrov was in a panic. If his mistress were to turn into a blackmailer, he would be at her mercy for the rest of his life.

“What are you going to do?” asked Vladik.

“Well, I don’t really know. I’ve got to talk to her. I’ll try to settle the issue in an amicable manner.”

Vladik did not say anything, but disagreed with his father. He was painfully affected by his parents’ conflicted relationship. At the beginning, he tried to make them patch things up. Then he gave up, hoping things would work themselves out. He was glad to hear his dad saying, at last, that he was going to leave his mistress. But he knew too well how weak and wavering Vetrov was. At eighteen, he could see only one way to put an end to the mortal danger threatening his father.