Farewell (2 page)

Authors: Sergei Kostin

Spring 1981: The Reagan administration, still shaken by the assassination attempt on the new president by John Hinckley two months earlier, was in shock again. A socialist, François Mitterrand, was elected president of a major European power with nuclear weapons. The new French government included four communist ministers, allies of the Socialist Party. Even though France was not officially part of the NATO military organization, the role it played in the free world’s defense structure could not be discounted. The rest of the West was getting so worried that United States vice president George H. W. Bush paid a visit to the Elysée Palace to express those anxieties in person. International reservations toward France remained on the agenda during the G7 summit held in Ottawa in July 1981.

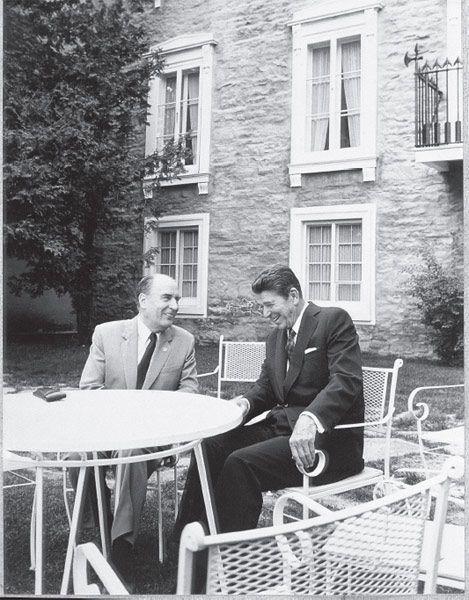

At the summit, despite the reluctance he was sensing, President Mitterrand appeared very confident. He knew perfectly well that this was not militant communism making a spectacular breakthrough within the Western Bloc. To the contrary, the West was now enjoying a major advance into Soviet front lines. For the past few months, France had had a mole, code name “Farewell,” operating at the heart of one of the most sensitive divisions of the KGB. During a face-to-face meeting, Mitterrand shared this secret with Ronald Reagan and revealed to him the scope of global Soviet industrial pillage. At the time, the American president did not fully understand the impact of the dossier, but he was a fast learner. Soon after, he would refer to it as “the greatest spy story of the twentieth century.”

Mitterrand-Reagan private conversation in Ottawa on July 19, 1981. The two presidents are relaxed and already in connivance: the disclosure of the Farewell dossier changed entirely the attitude of the leader of the Western Bloc toward the Socialist president.

The Farewell dossier should be presented in this context. Located at a strategic node within the system, this officer opened the eyes of the West to the scope, structure, and operations of technological espionage as practiced by the USSR, primarily in the military-industrial complex. The free world suddenly realized the vulnerability of those very defense systems vital to its survival. Furthermore, it became clear that it was impossible to have the upper hand in the arms race against the East because, through the efforts of Soviet intelligence, it did not take long for the West to “share” its most efficient weapons and devices with this formidable adversary. Finally, the scale of this systematic stealing revealed a key strategic weakness of the socialist bloc in the domain of high technology. A window of opportunity to bankrupt the Soviet economy was open for the new American administration, who did not expect the Cold War to remain frozen forever. Under the leadership of Ronald Reagan, who had been informed of the Farewell operation less than five months after it all began, the NATO countries significantly toughened their attitude toward the USSR and its satellites. Many remember the anxiety the world was experiencing during the first five years of the 1980s. After a short-lived détente, the Cold War was back in full swing, heating up to the point that it could less and less be described as “cold.” Fear of an apocalypse resurfaced after cascading events, including the downing of a South Korean aircraft, the Euromissile crisis, and Reagan’s joke during a mic check that he had signed legislation outlawing the Soviet Union, and bombing would begin in five minutes.

In the face of an unwavering position on the part of the USA, the Soviets no longer held such a good hand. World peace would have crumbled overnight had the president of the United States been matched by an equally stubborn and entrenched Kremlin leader, and the Soviet gerontocracy contained many such characters. Shaken, the communist regime under Yuri Andropov’s leadership kept trying to revamp its façade, but would not change a thing in substance. After Andropov’s death, the degradation of the international climate brought Mikhail Gorbachev to power. Being a flexible politician, Gorbachev eventually cooperated with the West to find a solution allowing the world to survive. The rest is history.

Therefore, it is tempting to think that without Farewell’s solitary action—whose motivations were miles away from reshaping the world—perestroika and the end of the Cold War could very well have occurred ten, fifteen, or even twenty years later, assuming that world peace could wait that long.

Undeniably, the factors leading to the collapse of European communism as a system are more numerous and complex, but only in the world of espionage can small acts have such great effects. The actions of a single person with access to the secrets of a major power have the potential to modify the course of history. Thus, among the “subjective factors,” to use Marxist terminology, the Farewell case certainly is in a class of its own. It was one of those stones that, as they crumble, cause the wall to collapse.

The Farewell file is also the most disturbing case there ever was, with so many improbabilities and paradoxes that many people will even doubt that it really happened. Judge for yourself.

A KGB officer, Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Ippolitovich Vetrov, decided to betray the system. However, instead of contacting the Americans, he chose to contact the French secret services—the ranking of which, in the world of intelligence, was modest at best, and which had no presence at all in Moscow. Moreover, Farewell had not called upon the French intelligence service SDECE (equivalent to the CIA), but rather upon the DST (equivalent to the FBI), a counterintelligence organization that had neither the spy handling experience nor legal authority to gather information outside French territory.

In order to handle this agent in Moscow, the DST began with an amateur who agreed to go along for the ride. This volunteer was then replaced by an officer, also with no experience in agent handling, from military intelligence operating under the cover of the French embassy. It is hard to believe that these two “amateurs” managed to meet routinely with their mole over a period of ten months, right under the KGB’s nose, without ever falling into the world’s most powerful police machine’s traps.

It is also difficult to imagine that a man acting alone, at great personal risk, could have stolen so many state secrets from the Soviet regime, managing to shake the whole edifice.

All this is quite understandable. Gus W. Weiss, one of the most respected among Reagan’s national security advisers, who knew the Farewell file very well, was probably the best man to express this murky feeling. “Devotees of 007,” he wrote, “are fiercely skeptical of Farewell’s authenticity, dismissing the adventures as a preposterous trunk of extravagant nonsense, sniping, ‘Buddy, you like got some kind of runaway imagination.’ It’s doubtful that a master of even Fleming’s dexterity could have persuasively stitched together as fiction the factual artillery of the Vetrov operation.”

1

Our ambition was, therefore, to try to reconstruct, as fully and truly as possible, this epic story mixing big politics and small existential disappointments, espionage and ideology, courage and villainy, love and hatred, calculations and madness, crime and punishment.

Sergei Kostin and Eric Raynaud

Moscow – Paris, January 2011

Proletarian Beginnings

To get close to the truth, Farewell’s personality and inner motivations matter as much as the suspenseful, sensational side of this espionage story. It would have been impossible to learn as much as we did about Vetrov’s biography, his character, and his personal tics—elements that bring life to the portrait of a man—without his family’s contribution. We are therefore deeply indebted to his wife Svetlana, who, after much hesitation, finally agreed to tell Sergei Kostin about her husband.

Kostin had been introduced to Svetlana through a close friend of the Vetrovs, Alexei Rogatin. This character appears sporadically throughout this story. Although he was very well prepared after some twenty years of investigations, Sergei Kostin was nevertheless impressed when he entered the building where the man he had been thinking about constantly for over a year had lived. He rode the same old elevator Vetrov had himself ridden; he rang the doorbell and stepped into the living room still decorated with the Tamerlane-themed wallpaper that the couple had brought back from their stay in France. The moment was intense since Kostin did not know whether he would be able to come back to this place.

During the two months to follow, he found himself every week sitting on a luxurious couch, surrounded by paintings and antique furniture. On the first visit, he joked to Svetlana, “I was told that you were working in a museum. I assume this is it, right?” As they became better acquainted with each visit, Kostin realized that this was indeed not so far-fetched. Svetlana, a woman with taste, had surrounded herself with rare and precious objects she had managed to save through the most difficult times of her life. This corresponds to her perception of herself, a rare and precious item needing good care. She certainly was very successful at it: no one could guess her age.

It became clear that Svetlana would only tell a personal version of the story. Like most of us, having gone through a traumatic experience, she had probably replayed the most painful moments over and over in her mind until they formed a more or less coherent and acceptable picture. Significant events are sometimes omitted because they are not flattering for the narrator, and little self-serving details are overly emphasized. There was no need to explain the unavoidable obstacle facing the journalist, as Svetlana is an intelligent woman. It was enough to give her the assurance that her words would not be distorted. It was agreed that Kostin would be free to keep his version of facts and events, and to use another version altogether if it was closer to the truth. This basic agreement turned out to be productive, and we believe we never betrayed its terms.

The reconstruction of the facts could not be comprehensive. There are topics a woman would never address on her own initiative, and there are questions you do not ask. Overall, Svetlana told Kostin much more than could be expected at the time, including things she is reproaching herself about to this day. Sometimes, in the excitement of the interviews, she went so far as to reveal certain points that she later on asked us not to mention in the book, a request which was respected. The fuzzy silhouette of the mythical Farewell was gradually becoming more precise; the character was becoming the man.

Vladimir Vetrov was born on October 10, 1932, in Moscow, in the well-known Grauerman maternity ward, where so many generations of native Muscovites came into this world. Visits were not allowed in this sanctuary of hygiene. Vladimir’s father, Ippolit Vasilevich, just stood there, in front of the building, to see his wife holding his son in her arms through a distant window. His first and only child, little Volodia would have no siblings.

Ippolit Vasilevich Vetrov was no aristocrat, old or new style. He was born in 1906 in a village in the Orel region. During World War II, he was a private first class, then a corporal, and he was among the very few drafted in the summer of 1941 who came back. He served as a cook on the Volkhov front in the middle of the Battle of Leningrad. After months spent in swamps, he developed a chronic chill. But Ippolit Vasilevich was strong and cheerful. He ended his career as a supervisor at a propane plant, filling canisters. He was a brave soldier, a model worker, and a good family man—a straight and honest man.

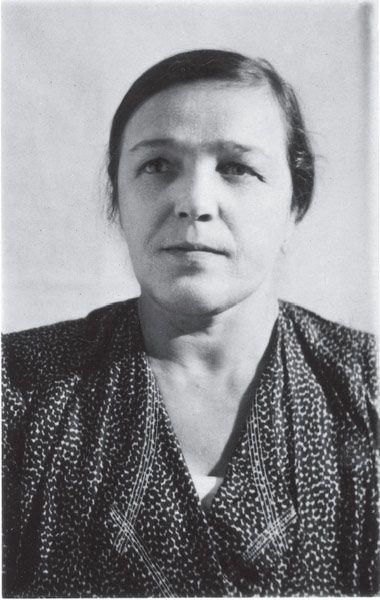

The master spy had modest origins. His father, Corporal Ippolit Vasilevich Vetrov, was among the lucky 5 percent still alive on Victory Day from those mobilized in the summer of 1941.

With little education, but a lot of strength and good sense, his mother Maria Danilovna ran the household.

Vladimir’s mother, Maria Danilovna, grew up in the Simbirsk region (later renamed Ulyanovsk) in a farming family having a hard time making ends meet. She had the same first name as one of her three older sisters because she too was born on a day dedicated to the Virgin Mary and to Maria Magdalena. To change a first name, the church required a symbolic fee that the family could not afford. So she kept the same first name as her mother and her sister.

She went to Moscow in search of work. Because she was illiterate and had no skills, she got a job as a maid. She had plenty of good sense and willpower. During the war, she was a team leader at a gauze manufacturing plant. Others would tell her, “Maria, if you had gone to school, you could have been our director.” She was also the head of her household, managing it masterfully without ever hurting her husband’s self-esteem.

The couple’s relationship was touching. They were very affectionate and caring toward one another. After their son’s birth, Ippolit Vasilevich would never call his wife any other way than “little mommy” or “sweet mom.” He would never leave the house without kissing her goodbye, and he liked to tease her. Alluding to the fact that Maria Danilovna was three years older than him, he would joke about the fact that “she never told me anything, naughty girl, she had me without saying a thing!”

Volodia grew up in this atmosphere of perfect understanding. As long as he was living with them, his parents never had any serious conflicts. The couple adored their boy, an intelligent and serious child. Volodia got along just fine with his father, but he was closer to his mother. He had what could be summed up as a happy childhood, essential to the psychological development of a well-rounded individual.

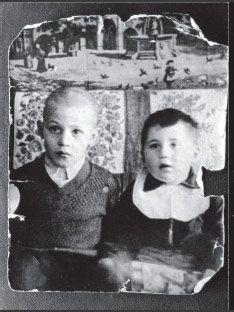

The only childhood photograph of Vladimir (left). Although a little shy in front of the camera, the boy has an inquiring look compared to his companion.

On the material front, things were difficult. The 1930s and 1940s were tough years for ordinary citizens who did not have any of the perks that Communist Party and government officials (apparatchiki) were enjoying, and who did not have their own plot of land to grow vegetables. Vladimir always remembered that every extra slice of bread was a feast, even more so with a little bit of sugar.

The building located at 26 Kirov Street where Vladimir Vetrov lived with his parents. In this neighborhood near the KGB headquarters, top members of the Soviet nomenklatura (ruling class) were living next to working-class people. Vladimir belonged to the latter while dreaming of joining the former.

The family lived at 26 Kirov Street, in a half-century-old commercial building, next to the post office. For the three of them, the Vetrovs were allocated one single room, long and narrow like a corridor, in a communal apartment where they had to share the kitchen and the bathroom with several other families. For most citizens, this was the normal way of life, and nobody would have thought to complain about it.

After the war, many teenagers were left without a father. In the labyrinth of yards, passages, and mews of downtown Moscow, gangs would form, soon to be on the slippery road to delinquency. Some of Vladimir’s schoolmates and neighbors ended badly. Some were sentenced and sent to jail for shoplifting. Others became alcoholics. There was a liquor store close by, which attracted easy trafficking of all kinds. Vladimir, however, benefited from a double protection—his family and sports.

He devoted all his free time to athletics. Sports were given a high priority in the education of Soviet youth. Sporting events helped promote a positive image of the Soviet Union abroad. Athletes enjoyed many significant benefits. Training sessions, totaling several months a year, often took place in resort towns by the Black Sea and in other sought-after destinations. During the training season, as well as during competitions, athletes were entirely taken care of by their sports club. The rest of the time, they all received food vouchers they could use to pay for meals anywhere they wanted, except in fancy restaurants. In addition, beyond a certain level, athletes received a sports grant from the government. While still in school, Volodia was receiving 120 rubles a month, the salary of an engineer or a physician. Proud not to be a burden for his parents, the boy gave all of that money to his mother. This was more than what she earned.

Most of all, Volodia was a good sprinter. He reached the peak of his athletic career when he became the USSR champion, junior division, in 100-, 200-, and 400-meter races.

His school was a five-minute walk from home, on Armiansky Alley. Pupils were a mix of the nomenklatura’s offspring and ordinary citizens’ children. It was an elegant neighborhood where quite a few members of the NKVD (the precursor of the KGB) lived, since the headquarters were close by. In fact, attending this school is what opened the boy’s eyes about the inequalities of Soviet society. Years later, Volodia would remember the subservient attitude of teachers toward the children of those Communist big shots. Other kids like him, whose parents never brought gifts to teachers, were viewed as future delinquents, with a sense of morals bound to fall apart the minute they left this temple of education.

His schoolteacher could not believe that the Vetrov kid had been admitted to the Bauman Moscow Higher Technical School (MVTU). This institution was probably the most prestigious engineering school in the Soviet Union, comparable to what Lomonosov University was in the humanities and research. The competitive entrance exam was draconian, and for each available opening for a student, with or without a scholarship, there were between ten to fifteen applicants. Vladimir was admitted in 1951, at a time when the country was still very enthusiastic about industrialization and the design of ever more intelligent and better performing machines. Engineers were the future, and the acronym MVTU resounded a little like MIT in the U.S.