Financial Markets Operations Management (42 page)

Read Financial Markets Operations Management Online

Authors: Keith Dickinson

We have covered several of the more usual types of corporate action event. There are, of course, many others and their definitions can be found in Appendix 11.1 at the end of this chapter. There can be confusion with some events that impact on the share capital, the par value of shares and the total number of shares in issue.

Table 11.27

highlights some of these differences.

TABLE 11.27

Other corporate actions

| Event | Capital Increase/Decrease | Par Value of Shares | Number of Issued Shares |

| Capital increase | Up | Up | N/A |

| Reduction of issued shares | Down | N/A | Down |

| Reduction of face value | Down | Down | N/A |

| Subdivision (split) | N/A | Down | Up |

| Consolidation (reverse split) | N/A | Up | Down |

Finally, let's look at the ways in which ratios of new shares to existing shares can differ from one market to another. The classic example is comparing the USA with most other markets. For example, when we looked at the RBS group bonus issue (above), we saw that the ratio was

two new shares for every one existing share, i.e. a 2:1 ratio. We also saw that, by implication, the number of shares post-event was three. Had this been a bonus issue in the USA, the ratio would have been 3:1; in other words, the shareholder would have a total of three shares post-event when he had one share ante-event.

It can therefore be seen that both these ratios are, in effect, the same â they are just quoted differently. This can make it potentially confusing for clients/shareholders when, for example, a European-based custodian passes on information to a USA-based client. One way to mitigate against any potential for confusion is to additionally state the number of shares the client owns, the number of shares the client will receive (or deliver) and the number of shares after the event has been completed.

Earlier we saw the nine processes that are required for the majority of corporate action events. To summarise, here are the nine headings:

- Event announcement;

- Reconciliation (ante-event);

- Event creation;

- Claims processing;

- Instructions processing;

- Entitlement calculation;

- Payment;

- Reconciliation (post-event);

- Reporting.

You will not require all of these in every situation, for example, there are no payments with bonus issues or bond conversions. Claims processing may not be required and mandatory events do not require any instructions to be submitted. Nevertheless, this list acts as a good

aide memoire

.

We took a quick look at the communication chain between issuer and investor in

Figure 11.1

. In this section we will analyse the problems of communicating and some of the solutions.

Unlike settlements and clearing, where there is a high degree of standardisation within different asset classes and across different markets, corporate actions are both complex and often complicated, due mainly to the non-standardised nature of a very broad range of event types. Add to this the difficulties of communicating in different languages and across time zones and country borders, and it is amazing that the industry does not experience more problems than it does.

The problem of complexity is not something that the industry has a great deal of influence over, as it is the issuer's choice as to what it wants to do and how it wishes to tailor the events in order to suit its own particular situation.

We have seen that unless there is a direct communication link between issuer and investor, there has to be a group of intermediaries between them. We will now examine the approaches taken in communicating information from issuer to investor and from investor back to the issuer. The following Figures will help you to understand the different approaches that we need to consider depending on what types of organisation are contained in the communication chain.

There are more detailed explanations in the chapter.

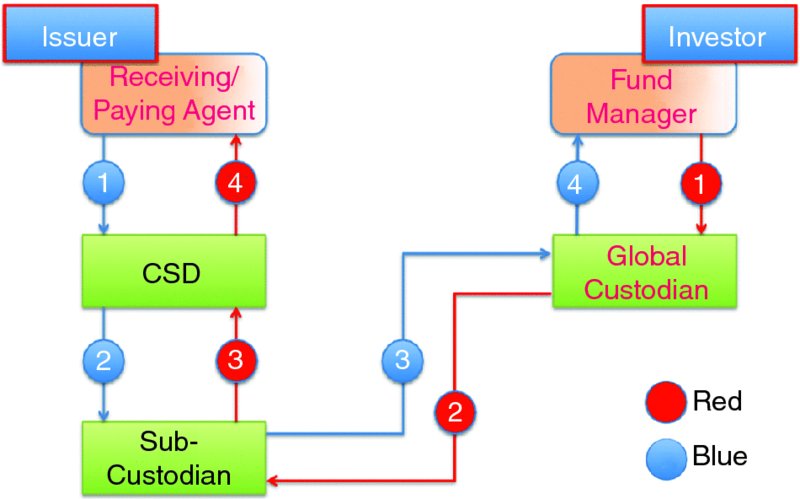

The various items of information transmitted from issuer to investor are highlighted in blue in

Figure 11.4

and the corresponding decisions in the opposite direction are highlighted in red.

FIGURE 11.4

Communication via global custodian

If we consider the more difficult scenario of an announced/voluntary event, such as a rights issue, and complicate it by placing the issuer and investor in two separate countries, then we have the potential for a difficult situation. We have seen in the section on rights issues that there is not a great deal of time from the announcement to the last day for acceptance and payment; there are also inherent dangers associated with the voluntary nature of the event.

Blue point 1 in

Figure 11.4

shows the starting point for any information and announcements made by the issuer; its agent will pass the information on to the appropriate CSD and from there (blue point 2) to the sub-custodian acting on behalf of its client the global custodian (blue point 3). The information from blue points 1 to 3 has, in all probability, been sent via the standard message types developed by SWIFT. These messages are not only standardised and authenticated but also used by the four intermediary types. There is a weakness, however, in that the issuer on the one hand and the fund manager on the other may not be direct participants in the SWIFT network. If they are not direct participants, they are unable to use the appropriate message types and instead will be required to use alternative methods of communication, such as emails, faxes, hardcopy messages, etc. The disadvantages of these alternative methods include the extra time and effort required to prepare, check, transmit, receive and re-enter into SWIFT message format. There is also the risk that incoming information may be re-keyed incorrectly, resulting in inaccurate or incorrect information going from giver to taker. What might the solution be? Permit all participants involved to have direct access to the SWIFT message type. In so doing, the processing will become closer to the straight-through processing ideal.

FIGURE 11.5

Communication via local custodian

Let us consider that the information has been received by the fund manager in a timely and accurate manner (in spite of the potential problems noted above). The information has been received by the fund manager's Corporate Actions Department, where appropriate checks have to be made to verify the information, enter the details into the systems and submit details to the Front Office staff for a decision. Remember that Operations Departments are not authorised to make decisions of this nature; it is for the Front Office to do this.

Now let us consider the amount of time required to relay the decision details from the investor's fund manager to the issuer's agent.

If we work back from the last day for acceptance and payment on a rights issue to the time when the Front Office has to make its decision, we might have the timeline shown in

Table 11.29

.

TABLE 11.29

Decision timeline

| Process | Number of Days Lead Time | Date |

| Last day for acceptance and payment (from CSD) | Last day (LD) | Friday, 30 May 2014 @ 12:00 |

| CSD to receive decisions from its clients (sub-custodians) | LD â 2 | Wednesday, 28 May 2014 @ 17:00 |

| Sub-custodians to receive decisions from their clients (global custodians) | LD â 3 | Tuesday, 27 May 2014 @ 17:00 |

| Global custodians to receive decisions from their clients' fund managers | LD â 5 | Friday, 23 May 2014 @ 15:00 |

| Fund managers to receive decision from their Front Office | LD â 5 | Friday, 23 May 2014 @ 12:00 |

We can therefore see that the Front Office is required to make its decision as to whether to accept the rights issue one week in advance of the Last Day. How do you think the fund manager will respond to that? It would not be unreasonable for the fund manager to request that a decision is delayed until the actual Last Day, and furthermore as close as possible to the deadline time.

Why would this be the case? The answer is simple (for the fund manager) but a challenge for the Corporate Actions staff dealing with this; a lot can happen in the markets and, for this particular event, it is a question of whether the Subscription Cost is at an acceptable discount to the market price of the shares. It would be a bad investment decision to accept a Subscription Cost of, say, EUR 15 per new share if the market price of the existing shares were, say, EUR 11 per share.

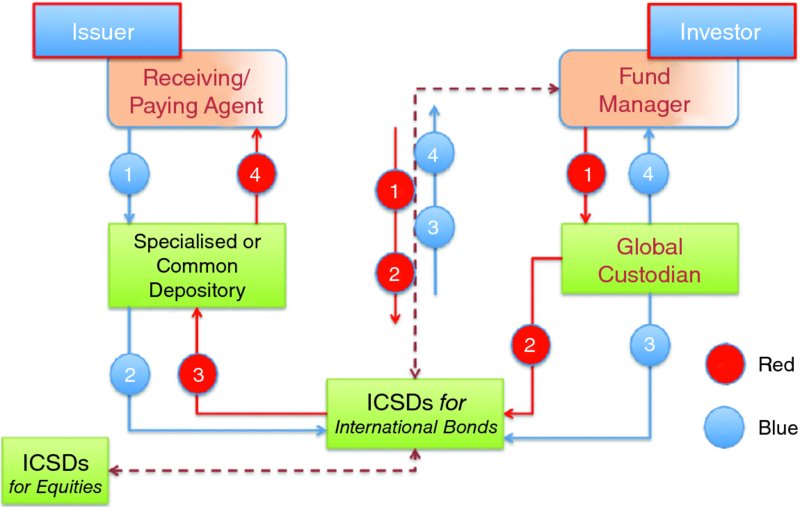

The intermediaries are therefore wishing to receive a decision (blue point 4 in

Figure 11.6

) as early as possible whilst the decision-maker wants to delay this until the last possible moment. There is, however, a degree of flexibility within each of the individual intermediary's own internal deadlines. This is to allow as much time as possible for their clients to make a response.

FIGURE 11.6

ICSD communication with depository, global custodian and fund manager

A global custodian will, for example, add the following rider to its request for a decision: “If we do not hear from you by < time> on < date>, we will take no action. If, however, we do receive your instruction after this deadline but before the Last Date, we will attempt to submit your instructions on a âbest efforts' basis. If these instructions miss the issuer's own deadlines, we will not be held accountable and will not make your client(s) âgood' as a result.”

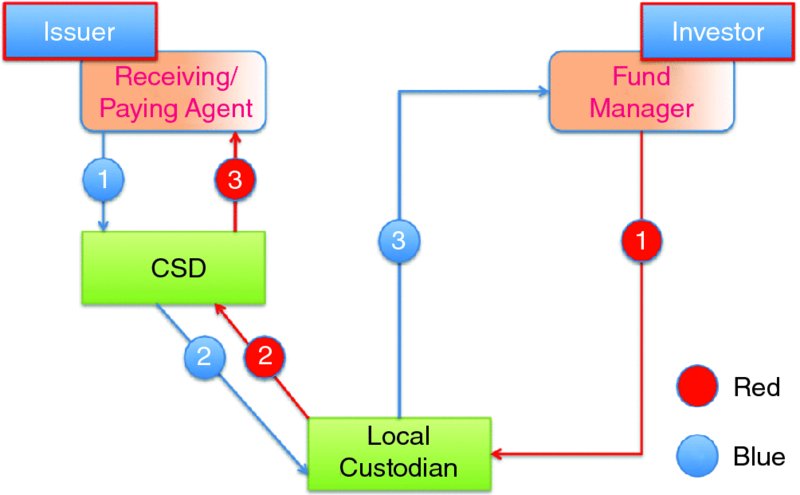

The communication issues in a local context are not such a problem. The global custodian, with its cross-border perspective, is now removed from the chain and the problems of language, time zones and different processing practices no longer apply. The banks that act as sub-custodians now act in a local custodian capacity, as shown in

Figure 11.5

.

The previous communication chains apply predominantly to equity securities. With respect to international securities, such as Eurobonds, we bring the two ICSDs into the frame.

We can therefore see from

Figure 11.6

that the global custodians and one or both of the ICSDs communicate with each other. For bond-related corporate actions, the ICSDs communicate with either a specialised or common depository (depending on the way the bonds are actually held).

In some situations, the ICSDs have bilateral links with some CSDs and can communicate on equity-related corporate actions through these.

We have seen that it is rarely practical for issuer and investor to communicate directly with each other. The use of intermediaries is therefore required and, depending on the types of intermediary, there are going to be communication difficulties.

The longer the communication chain, the more time is required to make sure that the investor is informed of any corporate action details as quickly and as accurately as possible. The same is required once the investor has made a decision on an optional event, so that the investor can benefit from any choices that are available.

Having a standardised communication system, such as the message types provided by SWIFT, certainly eases many of the communication difficulties, as does the inclusion of investors and issuers on the SWIFT network.