Finding Arthur (12 page)

Authors: Adam Ardrey

Tags: #HIS000000; HIS015000; BIO014000; BIO000000; BIO006000

The 1860

Roll of Valuation of Tenements for the Parish of Killeeshil, Co. Tyrone

, names twenty-two property holders in Mullnahunch, including, as the last name on the list, John of 1798. He held three roods (3,630 square yards of land), on which were erected a house and an outhouse. The largest landholding in Mullnahunch was sixty acres or 290,000 square yards. Even John’s next door neighbor, John Beadmead, had four acres three roods or 22,990 square yards.

My John was obviously of modest means; indeed, if the value of his tenement is anything to go by, he seems to have headed one of the poorest families in the area. When John of 1798 died, his youngest son, David, my great-grandfather, signed his father’s death certificate with his mark, a cross, which means, almost certainly, that my grandfather Adam was the first in my direct line of Ardreys who could read and write.

Illiteracy was common in Ireland in the nineteenth century, and consequently family names, especially unusual family names, were often variously spelled. Men such as my great-grandfather had to rely on clerks to listen carefully and make an accurate record. There was the added complication that, for political and economic reasons, Scottish names were often Anglicized by people whose first language was not

Gaelic, hence the innumerable spellings of my second name in the records: these include Ardray, Ardary, Ardery, Ardry, Ardree, Ardrie, Airdrie, Airdrey, Ardrea, Arderly, Artrey, Arderey, Arderry, Artery, Adderley, Aredrey, Ardarie, Ardare, Ardarike, and even Dare. (This sometimes had unfortunate consequences. My great-grandfather David’s brother, George, married Eliza, John Bedmead’s daughter, the girl-next-door in the village of Mullnahunch. Eliza’s name was written into the records as, variously, Bedmaid and Bedmate by clerks who no doubt thought this was funny. And it is … a bit.)

John Bedmead (father of Eliza of the user-friendly name) brought shoemaking into my family and by the middle of the nineteenth century my Ardreys were running a small shop in Mullnahunch where they manufactured and sold boots and shoes and pots and pans, and sold candles, salt, clothes, and eggs and other farm produce.

Following his father’s death, my great-grandfather David immigrated to Scotland and found work as a car conductor. It was in the early 1990s while I was looking for David’s first home in Glasgow—60 McLean Street, Plantation—that I came across an Ardery Street, a mile and a half away, over the river on the north bank of the Clyde. I wondered if this Ardery Street had anything to do with my David, though the spelling differed from my own name. I did not think that this may have been where the man called Merlin lived in the last two decades of his long life, after he was driven out of town by Mungo Kentigern’s Christians. I was not to discover the evidence for this for more than a decade.

In the 1870s a young Martha Milligan was sent from her home in Kilmarnock to work as a domestic servant in Glasgow. I picture her meeting my great-grandfather David when she was a passenger on his bus going to her work. They were married in 1877. Martha’s family found David work as a railway pointsman in Riccarton, Kilmarnock, and by the time their first son, John, was born they were living in Railway Buildings, Barleith, Kilmarnock. Seven other children followed; the last of them was my grandfather Adam. He was born in 1893, after David and Martha had moved to Coatbridge and opened a shop where they made and sold boots and shoes. The only surviving photograph of David shows a man with a large moustache

wearing an apron and standing at the door of his shop near the fountain that marks the center of Coatbridge. My grandfather Adam, an Assistant Registrar of Births, Deaths, and Marriages in Baillieston, Glasgow, had two sons;

1

my father, another David, was the older of the two.

I served my legal apprenticeship in a solicitor’s office that, I have always suspected, was a portal to the world of Charles Dickens. One of my jobs was to catalog deeds that had been left untouched in black tin boxes in the basement since before I was born. It was on one of these frolics, while working on documents concerning property in Argyll, that I crackled open a title deed that was dry in every sense and saw my second name on a map, on the banks of Loch Awe, Argyll. The spelling was slightly different,

Ardray

, but I knew old spellings were variable things. I had not known that my name had any connection with Argyll until then, but I had always known of my Protestant Irish connection and so an Argyll connection made sense.

I contacted the Forestry Commission and the people there sent me older and more detailed maps. In the early 1980s, with these to guide me, I drove north along the east side of Loch Awe, past the remains of the ancient church of Kilneuair and the ruins of Fincharn Castle, looking for the lands of Ardray. There is now a picnic site at Ardray, but when I was looking for it that first time there was nothing to suggest where it was, and so I had to use dead-reckoning. I estimated how far it lay from the crossroads at Ford at the southern end of the loch and used my car odometer to count the miles. I also counted burns as I passed, having worked out that Ardray lay between the fifth and sixth burns that ran into the loch, but identifying what was and was not a burn wasn’t easy, far less telling one burn from another. I might as well have followed the second star to the right for all the good any of this did me. I searched all day but found nothing.

On my last night in Argyll, in the bar of the Ford Hotel where I was staying, I told the Forestry Commission workmen who were drinking there my problem. They said they knew where Ardray was and that there were ruins there. They then took a broken dart from the hotel dartboard and a red paper napkin from a table and promised me that on their way home that night they would mark the site of Ardray by

pinning the napkin to a tree with the dart. The next day I saw the napkin, walked uphill into the woods, and found the Ardray ruins, a stone shell of a building standing on the bank of a burn.

A few years later, on the same weekend in which we visited Ardery in Sunart, I again tried to find Ardray on Loch Awe, to show it to Dorothy-Anne, but I couldn’t find it. It was only later that I wondered what she must have thought as she stood there in the rain watching me, her new husband, slipping and sliding as I ran in and out of the trees looking for what, at that time, I was calling my “ancient family home.” It was not a scene that compared well with Mr. Darcy showing Pemberley to Elizabeth Bennet.

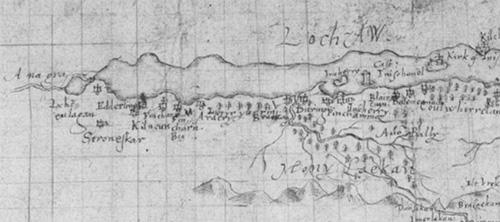

Ardray was not always such an obscure place. It is clear from Timothy Pont’s sixteenth-century maps that there was something significant there in his day.

2

Pont marks Ardray (or, as he spells it, Ardery) with a symbol that looks like two tubes above a small circle, but as no one knows what Pont meant by many of the symbols he used and because he was not always consistent, it is impossible to be sure from his map what was originally there or when it was built. The Ardray-Ardery symbol, two parallel tubes, is very uncommon, if not unique. I can find no other symbol like it on Pont’s maps.

3

The nearest things to the symbol Pont used to mark Ardray-Ardery on Loch Awe are the symbols he used to mark relatively important buildings: churches and fortified places. Almost all of Pont’s churches and fortified places have a circle symbolizing a settlement nearby, as does Ardray-Ardery.

I was a new lawyer, with lots to learn, and so I did not pursue the matter of my name and family further at that time. Almost ten years later, in 1993, I was driving south of the Kilmartin Glen, along the side of the Crinan Canal to the Mull of Kintyre, to view land that was the subject of a legal dispute in Dunoon Sheriff Court, when I saw a hand-painted sign nailed to a tree with the word

Dunardry

written on it.

I understood this

Dunardry

to be

Dun Ard Airigh

, “Hillfort of the High Pasture,” a rather insipid name and one that did not seem right to me. There are high pastures all over Argyll. Why would anyone call such a vital fortified place, one that commanded the most important route in Argyll and which was situated only a short distance from

Dunadd, the ceremonial capital of Dalriada, by such a bland name? Hillfort of the High Pasture just did not make sense.

Dunardry is a large flat-topped hill that looms over the portage route that ran along the narrow neck of land that separated Knapdale and Kintyre for thousands of years, until the Crinan Canal was built in the early nineteenth century to connect Loch Fyne and the interior of Scotland to the Sound of Jura and the Atlantic Ocean. Dunardry was of vital strategic importance, even more so than the more famous hillfort at Dunadd, the first seat of the Scots kings of Dalriada, which lies less than two miles to the north.

Dunadd, a rocky plug some 175 feet high, stands proud in the Moine Mhor, the Great Moss that stretches west to the Sound of Jura. (The Great Moss is now a bird sanctuary.) In its prime Dunadd had four walls on different levels, with terraces accessed by massive gates. On the summit, carved in a flat expanse of rock, is the figure of a boar, a symbol of Argyll; a cup shape, for which there is no generally accepted explanation; and a footprint, which played a part in inaugurations of the kings of the Scots. Nearby is inscribed a single line of as yet un-translated ogham text.

Dunadd is generally accepted as the capital fort of Dalriada, although there is reason to believe there was another, now lost, capital. As the toponymist William Watson writes, “Where was the capital of Scottish Dalriada? Since the middle of the last century [the nineteenth] it has been supposed that Dunadd … was the capital—a theory championed by Skene … though some of the literary evidence used by him refers to another site, unidentified

Dun Monaidh

.”

4

I thought again of my

Righ

-

Airigh

conundrum. The men who gave the fort its name were warriors. Why would they have named a vital stronghold “the hillfort of the High Pasture,” when the name “hillfort of the High King” was obviously more appropriate? Although I accepted what I had been told, I still felt that I was missing something. Perhaps, I thought, my name meant “High King” after all; perhaps

Dunardry

did mean “Hillfort of the High King”; perhaps it was and always would be impossible to be sure.

My surname was of interest to me because it was mine and so, naturally, of little or no interest to anyone else. The whole point of

family history is that it is personal. Being personal, it leads people down un-trodden paths and allows them to find things no one else has found (primarily because no one else cares enough to discover them). That is how it was for me.

Timothy Pont’s sixteenth century map of Loch Awe showing one of the many Ard Airigh (Ardery/Ardrey) place-names in Argyll. This place-name on Loch Awe prompted my search for Arthur

.

©

Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the National Library of Scotland

.

In the year 2000 I was planning a weekend break with my then nine-year-old son, Eliot, in Kilmartin, Argyll, because of its Ardrey associations. The Kilmartin Glen is one of the most important archaeological sites in Europe. There are at least 350 ancient monuments —stone circles, standing stones, cup-and-ring marks, and cist graves—within a six-mile radius of Kilmartin village. (I was proceeding in the belief that nine-year-old boys enjoy visiting ancient monuments. I did when I was nine.)

Kilmartin became famous in the 1980s following the publication of the book

The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail

and follow-up books that claimed that survivors of the Knights Templar came to Kilmartin as refugees after their order was destroyed by the French king Philip the Fair and his henchman Pope Clement V, on Friday, October 13, 1307.

This idea added mystery to the history of the Glen and provided me with more stories to tell my son. (I was also proceeding in the belief that my son liked to hear me talk a lot. I did when I was nine.)

The scenery, the history, the mystery, the football (on the car radio), the good food, and watching

The Guns of Navarone

on the TV in our B&B made that weekend one of the best times of my life.

The day before we left for Argyll I went through the “secret” passage that led from the Advocates’ Library where I work to the National Library of Scotland. I had often used this passage before to visit the National Library to research something or other, or just to read books at random. This time, looking for more Ardrey-family connections with Argyll, I found nothing that was new to me in the gazetteers, and the dictionaries only confirmed what I had been told years before: that my name, Ardrey, was originally

Ard Airigh

in Gaelic and that it meant “high pasture.”

Then I found a dictionary that was new to me and everything changed.

John O’Brien, Roman Catholic Bishop of Cork and Cloyne in Ireland, wrote

Focalóir Gaoidhilge-Sax-Bhéarla: An Irish-English Dictionary

and had it privately printed in Paris in 1768. O’Brien said he compiled his dictionary,