Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership (88 page)

Authors: Conrad Black

BOOK: Flight of the Eagle: The Grand Strategies That Brought America From Colonial Dependence to World Leadership

11.88Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

On the same day the Berlin blockade was lifted, May 12, the Allied powers recognized the sovereign state of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), with its capital on the Rhine, at Bonn, largely because it was the home of Germany’s leading statesman, Christian Democrat Konrad Adenauer, who had been mayor of Cologne before the Nazi era, and had been persecuted during the Third Reich. Adenauer became the Federal Republic’s first chancellor. One of the greatest acts of statesmanship of the postwar world in the twentieth century would be Adenauer’s rejection of Stalin’s offer of reunification of Germany in exchange for Germany’s neutrality between the Soviet and Western blocs. Adenauer said that Germany would remain with its allies and would eventually be reunified anyway, as did occur, and he carried German opinion with him.

When Truman first started exploring, with Acheson, the possibilities for such an alliance, the Dutch had been chiefly concerned with retention of Indonesia, which was impossible; the French with subjugation of Germany, which was impractical; and the British with spiking the mystique of communism by making a success of democratic socialism in Britain, which, as Truman gently pointed out, was not going to deter Stalin’s armed forces, even if it were a success domestically (and it wasn’t). The Americans led the new alliance with great distinction, and Eisenhower retired from Columbia University to become the first military commander of NATO, and did his now very predictably inspired job of putting together a multinational, smoothly operating command structure for NATO in Paris.

In the Far East, MacArthur was proving an extremely deft and imaginative governor of Japan, instituting women’s rights, a democratic political system, and a free market economy, while preserving the emperor, with whom he developed a good relationship, and adapting Western reforms to Japanese folkways. He was deeply respected in Japan, and very attentive to the sensibilities of the Japanese. There was no Soviet presence in the country at all, except for a very modest military liaison office. MacArthur and other American experts in the area regularly warned Truman and his senior colleagues of the deteriorating situation in China. Mao Tse-tung’s Communists, better organized and galvanized by an ideological faith, steadily gained against Chiang Kai-shek’s corrupt and very compromised Nationalists. It was clear from Stalin’s comments at Tehran and Yalta and Potsdam that he had no great affinity for Mao or the Chinese Communists generally, but in the acutely defensive atmosphere that was developing, fed by reports of Communist espionage, the specter of a Communist takeover in China was a very disturbing one.

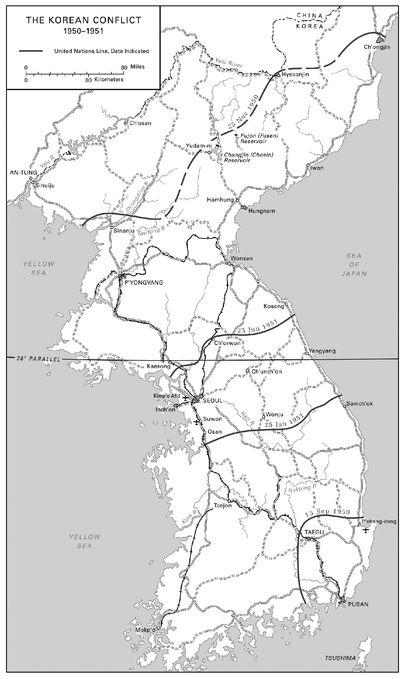

Korean War. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Center of Military History

The Red Scare was fueled by espionage controversies, which began with the defection of the Soviet cipher and coding clerk in the embassy in Ottawa, Canada, Igor Gouzenko, in September 1945. The information he dumped into the lap of the Canadian authorities, the FBI (as the CIA was just being assembled from the war-time Office of Strategic Services), and British MI5 led to the apprehension of Klaus Fuchs, the Americans Julius and Ethel Rosenberg (arrested in 1950 and executed on June 19, 1953), and ultimately the British spy ring of Guy Burgess, Donald MacLean, Kim Philby, Anthony Blunt, and John Cairncross. There were television programs in the United States dramatizing the Red Menace and constant warnings that anyone’s friends, neighbors, or even relatives could be communist spies. J. Edgar Hoover was making provocative speeches around the country about the Red Menace and New York’s Francis J. Cardinal Spellman claimed the country was in imminent danger of a communist takeover. This was preposterous; there were very few American communists, even fewer Soviet agents, and none of them in any positions of influence, but it rattled public confidence, though it helped produce the political support for a water-tight containment policy against the Soviet Union.

Former State Department official Alger Hiss was accused by Time magazine assistant editor Whittaker Chambers of having spied for the USSR in the thirties, and after he denied it, he was, by the efforts of California congressman Richard M. Nixon, indicted for perjury on December 15, 1948. The tense atmosphere was escalated and the capital shocked by the suicide of just-retired Secretary of Defense James V. Forrestal, who jumped from a 16th floor window at Bethesda Naval Hospital on May 22, 1949. He had had a depressive breakdown, but rumors abounded for a time that he had been murdered in a communist conspiracy (like Jan Masaryk in Prague the year before). Forrestal was succeeded by Louis A. Johnson, who moved quickly to cut costs but antagonized virtually everyone, and General Omar N. Bradley wrote that “unwittingly, Mr. Truman had replaced one mental case with another.”

139

139

By mid-1949, it was clear that Chiang Kai-shek was finished and was being routed by Mao Tse-tung.

Time

and

Life

publisher Henry R. Luce, who had been born to Christian missionaries in China, and believed in Chiang and his Wellesley-educated Christian wife, led the charge in support of the Chiangs, backed by an army of church and Republican groups, and by General Douglas MacArthur, who wrote for Luce’s mass-circulation publications at times. On August 4, 1949, the State Department published a document of over 1,000 pages on the history of U.S.-China relations, with particular emphasis on 1944 to 1949. In a foreword, Dean Acheson wrote that more than $2 billion had been given to Chiang, who was dismissed as corrupt and incompetent. Acheson concluded that the impending fall of China was the result of “internal Chinese forces ... which this country tried to influence but could not.” Truman told Senator Vandenberg: “We picked a bad horse.”

140

Republican demagogues, including California senator William Knowland and Wisconsin senator Joseph R. McCarthy (who had defeated Robert La Follette Jr., in a 180-degree ideological turn for Wisconsin), were not going to let Truman and the Democrats off that lightly.

Time

and

Life

publisher Henry R. Luce, who had been born to Christian missionaries in China, and believed in Chiang and his Wellesley-educated Christian wife, led the charge in support of the Chiangs, backed by an army of church and Republican groups, and by General Douglas MacArthur, who wrote for Luce’s mass-circulation publications at times. On August 4, 1949, the State Department published a document of over 1,000 pages on the history of U.S.-China relations, with particular emphasis on 1944 to 1949. In a foreword, Dean Acheson wrote that more than $2 billion had been given to Chiang, who was dismissed as corrupt and incompetent. Acheson concluded that the impending fall of China was the result of “internal Chinese forces ... which this country tried to influence but could not.” Truman told Senator Vandenberg: “We picked a bad horse.”

140

Republican demagogues, including California senator William Knowland and Wisconsin senator Joseph R. McCarthy (who had defeated Robert La Follette Jr., in a 180-degree ideological turn for Wisconsin), were not going to let Truman and the Democrats off that lightly.

As the Chinese Nationalists circled the drain, Stalin detonated an atomic bomb, on August 29, 1949. This led to an anguished, semi-public debate about whether the United States should proceed to a “super bomb,” the hydrogen bomb. This controversy was only resolved in favor of doing so on January 31, 1950, when Truman was satisfied that the Soviet Union would proceed to the same destination. The hydrogen bomb was tested by the United States on January 11, 1952, and it possessed the potential to be as much as 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In the meantime, Mao Tse-tung proclaimed the People’s Republic of China on October 10, 1949 (the 24th anniversary of the revolution of Chiang Kai-shek’s brother-in-law, Sun Yat-sen, although the relationship was posthumous to Sun), and almost all fighting had ceased on the Chinese mainland by December. Chiang had removed to Taiwan, and declared Taipei the temporary capital of the Republic of China. The United States Seventh Fleet, sailing from Japan, effectively assured Taiwan’s security from invasion, permanently thereafter, at least to the time of this writing.

8. THE COMMUNIST ATTACK IN KOREAOn January 12, 1950, in an address to the National Press Club, Acheson described the American defense perimeter. But by not mentioning South Korea he implied that it was outside the perimeter. Korea had been arbitrarily divided at the 38th parallel for the purposes of deciding whether the Japanese occupying forces should surrender to the United States or the Soviet Union. The demarcation had been decreed by two junior officers in the Pentagon one night in the summer of 1945, one of them, then Colonel Dean Rusk, a future secretary of state. The South had two-thirds of Korea’s population and a rather larger area, and was a little larger than the state of Indiana.

The junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy, announced in a speech to Republican women in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 6, 1950, that he had in his hand a list of 205 “known communists” in the State Department. He made similar speeches a few days later, in Salt Lake City and Reno, claiming that there were 57 “card-carrying communists” in the State Department, and this allegation received a good deal of publicity. Not long after, he gave a five-hour harangue in the Senate, and his allegation levitated to 81 communists in the State Department. He never produced a shred of evidence, had no evidence, and was treated with considerable skepticism in most of the media. But he struck a chord with a large echelon of opinion in a fearful America. McCarthy multiplied his fantastic allegations, denigrating Truman, Acheson, and ultimately Marshall. Some Republican senators, smarting from their decades out of office, lent support to McCarthy, even though they must have known what slanders his charges were. It is illustrative of the poor level to which public debate had sunk that anyone could take seriously allegations of treason against Acheson and Marshall, and of senescence against Truman himself, reducing him to manipulation by traitors.

On April 7, 1950, National Security Council Report No. 68, largely written by long-serving foreign and defense policy official Paul Nitze, under Acheson’s supervision, was handed to Truman, and warned that “This Republic and its citizens, in the ascendancy of their strength, stand in their deepest peril” because of wholly inadequate military strength to enforce its containment policy, given that, at that point, the Soviet Union was expected to achieve atomic parity within a few years. Truman was still considering how to respond to this strenuous rearmament recommendation from his national security team, including the senior military officers, when North Korea abruptly invaded South Korea on June 24. It was assumed that this was a Soviet-prompted aggression, in part motivated by its exclusion from Japan, and Truman was determined that it had to be responded to firmly and at once. He remembered Manchuria and Ethiopia and the disastrous consequences of the democracies not helping the victims of aggression by dictators. The United Nations was an American invention and “In this first big test, we just can’t let them down,” Truman said.

141

141

On June 27, with almost unanimous support from Congress by voice vote, and the complete solidarity of his national security group, military and civilian, and as North Korean tanks entered the South Korean capital of Seoul and North Korean leader Kim Il Sung promised to “crush” the South, Truman ordered full air and naval support of the South. MacArthur was already calling for ground intervention, and was causing concern about his independent-mindedness, even in the mind of Louis Johnson, who was generally considered a loose cannon himself.

142

Johnson, having just returned with Bradley from Tokyo, advised Truman to be very precise in any orders he sent MacArthur.

142

Johnson, having just returned with Bradley from Tokyo, advised Truman to be very precise in any orders he sent MacArthur.

At 10:45 on the evening of the 27th, the United Nations supported a resolution backing the United States action. Stalin and Molotov had made another serious error: their ambassador at the UN had been pulled in protest against the continued occupation of the Chinese Security Council chair and General Assembly membership by the Nationalists. For the first time, an international organization had approved military action. Acheson’s January 12 speech was resurrected by some and blamed for inciting the belief that the United States would not defend South Korea. The secretary’s omission of Korea was injudicious, but it is unlikely that Stalin, Mao, and Kim Il Sung relied on it overly in unleashing such an onslaught.

American opinion of every hue and source was practically unanimous; Walter Lippmann, James Reston, Joseph and Stewart Alsop, Thomas E. Dewey, Cordell Hull, all the influential newspapers and magazines, and an avalanche of uncontradicted messages from the public, spontaneously backed the president. Eisenhower said, “We’ll have a dozen Koreas soon if we don’t take a firm stand.”

143

At 3:30 a.m. on June 30, MacArthur reported to the Pentagon from Korea, where he was inspecting the situation for Truman and Bradley, that the South Koreans could not hold with air and sea support alone, and that two American divisions were needed at once. Truman responded immediately and authorized the movement of the forces MacArthur requested, from his occupation divisions in Japan. The Americans, as they arrived, and the South Koreans, were outnumbered three-to-one by the North, which was heavily armed and was spearheaded by a large number of the formidable Russian T-34 tanks. It was monsoon season in Korea and the temperature was steadily above 100 degrees.

143

At 3:30 a.m. on June 30, MacArthur reported to the Pentagon from Korea, where he was inspecting the situation for Truman and Bradley, that the South Koreans could not hold with air and sea support alone, and that two American divisions were needed at once. Truman responded immediately and authorized the movement of the forces MacArthur requested, from his occupation divisions in Japan. The Americans, as they arrived, and the South Koreans, were outnumbered three-to-one by the North, which was heavily armed and was spearheaded by a large number of the formidable Russian T-34 tanks. It was monsoon season in Korea and the temperature was steadily above 100 degrees.

MacArthur was now the United Nations theater commander (in Tokyo) and was conducting an orderly withdrawal, stretching North Korean supply lines and preparing a relatively solid defensive perimeter in the south of the peninsula. He had asked for 30,000 men at the beginning of July, and on July 9 for another four divisions. The UN forces were conducting a distinguished rearguard action and they yielded barely 100 miles throughout July. On July 29, the tactical battlefield commander, General Walton Walker, ordered his forces, around Pusan at the southern extremity of Korea, to “stand or die.” There would be no retreat—as he put it, “No Dunkirk, no Bataan.”

144

144

Other books

The Knight's Temptress (Lairds of the Loch) by Scott, Amanda

Cottage Daze by James Ross

Lucifer (Brimstone Heat Book 1) by Rayne Rachels

Rogue of the Isles by Cynthia Breeding

Mike's Election Guide by Michael Moore

Cry of the Peacock by V.R. Christensen

Walking Away by Boyd, Adriane

The Ship Who Sang by Anne McCaffrey