Forbidden History: Prehistoric Technologies, Extraterrestrial Intervention, and the Suppressed Origins of Civilization (27 page)

Authors: J. Douglas Kenyon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Fringe Science, #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #Ancient Aliens, #History

27

Ancient Agriculture, in Search of the Missing Links

Is the Inescapable Evidence of a Lost Fountainhead of Civilization to Be Found Growing in Our Fields?

Will Hart

O

ne of the most curious aspects of history’s mysteries is that there is anything mysterious to puzzle over. Why

should

our history be full of anomalies and enigmas? We have become conditioned to accept these incongruities, but if we turn the situation around, it really does not seem to make sense. We know the histories of America, Europe, Rome, and Greece with some precision back three thousand years, just as we know our own personal histories. We would consider it very odd and unacceptable if we did not.

However, when we go farther back into prehistory than Babylonia to Sumeria and ancient Egypt, things get very fuzzy. There can be few possible explanations: 1) our ideas and beliefs about the way history happened conflict with the truth; 2) we have collective amnesia for unknown reasons and/or some combination of both.

Imagine that you woke up one morning with complete amnesia, no idea of how you got on this planet and no memories of your own past. We are in an analogous situation regarding the history of civilization, and it is just as disturbing. Or let’s say that you are living in an old Victorian-style mansion full of odd, ancient artifacts. That is pretty much our situation as we wander around ancient ruins and through the galleries of museums wondering who made all this stuff, and how, and why.

One hundred and fifty years ago, much of the history in the Old Testament was considered pure fiction, including the existence of Sumeria (the biblical Shinar), Akkad, and Assyria. But those forgotten pieces of our past were discovered in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when Nineveh and Ur were found. Their artifacts have completely changed our view of history.

Until fairly recently, we did not know the roots of our own civilization. We had no idea who might have invented the wheel, agriculture, writing, cities, or any of the rest of it. Additionally, for some curious, inexplicable reason, not that many people cared to know, and even historians were willing to let the ruins of human history lie buried under the desert sands. That attitude seems as strange as the mysteries themselves.

Would you simply accept the situation if you had amnesia, or would you do everything in your power to reconstruct your past and your identity?

It seems that there is something we are hiding from ourselves. Some will say it was a mind-wrenching visit by ancient astronauts; others will argue there was an ancient human civilization destroyed by cataclysm. In either event, we have apparently buried and forgotten those episodes because the memory is too painful. Personally, I have not reached a final conclusion regarding those ideas; however, I am sure the orthodox theories presented by conventional archeologists, historians, and anthropologists do not hold up under intense scrutiny.

It is curious that we have developed the capability to send space probes to Mars and to crack the human genome, and even to clone ourselves, but we are still fumbling around trying to understand the mysteries of the pyramid cultures, of prehistory, and of how we made the quantum leap from the Stone Age to civilization in the first place! It does not add up. Why should we, as a species, not have maintained the threads directly and concretely linking us to our past?

I have this gut feeling that investigative reporters and homicide detectives get when they’ve been digging into an unsolved case for a long time. We are missing some pieces and/or we are not looking at the situation correctly, and we are probably overlooking the meaning of obvious clues because we have been conditioned to think about the facts in a certain way. Additionally, we have not asked all of the right questions. It never hurts to go back to basics and review everything you think you know and what the real “facts” are.

We have always had the choice of trying to make sense of the world or not. Life has given us an incredible amount of leeway and freedom when it comes to knowledge acquisition. Our ancestors mastered the basic rules of the game of survival during the incredibly long time span of the Stone Age. They did not need to know that Earth revolved around the Sun or the nature of atomic structure to succeed. But after the last ice age, something strange occurred, and the human race went through a sudden transformation that sent our race into unknown territory.

We are still reaping the consequences of those explosive events.

Let us go back and set the stage of early human evolution as science depicts it unfolding. Our ancestors found themselves in a world full of natural wonders, facing the challenges that nature set before them, all having to do with basic survival. To begin with, they had no tools and no choice other than to meet the challenges head-on, just as other animals did. We have to keep the realities of this background in perspective. We know exactly how Stone Age people lived because many tribes around the world were still living in this manner during the past five hundred years, and they have been studied intensively and extensively.

We know that humanity was fairly homogeneous throughout the Stone Age. Even 10,000 years ago, people lived pretty much the same way, whether they were in Africa, Asia, Europe, Australia, or the Americas. They lived very close to nature, hunting wildlife and gathering wild plants, using stone tools and stone, wood, and bone weapons. They had learned the art of making and controlling fire and they had very accurate and detailed knowledge about the habits of animals, the lay of the land, nature’s cycles, and how to distinguish between edible and poisonous plants.

This knowledge and their way of life had been painstakingly acquired over millions of years of experience. Stone Age humans have been wrongly portrayed and misunderstood. They were not stupid brutes, and there would be no modern mind and no modern civilization without the long evolution they went through to establish the basis for all that would eventually happen. They were keenly aware, entirely in communion with nature, and unquestionably stronger and more muscularly robust than we are today.

In reality, the natural world we inherited from Stone Age man was entirely intact. Everything was as pristine and virginal as it had been during the millions of years of human evolution. Nature bestowed her bounty upon those early humans and they learned to live within that natural framework. Viewed from a statistical perspective, the human status quo is the hunter-gatherer culture that we lived in for 99.99 percent of our existence as a species, at least according to modern science.

It is very easy to understand how our remote ancestors lived; life changed very little and very slowly. Early man adapted and stuck with what worked. It was a simple but demanding way of life that was passed on from generation to generation by example and oral tradition.

There really does not seem to be much mystery about it. But that all starts to change radically after the last ice age. Suddenly, a few tribes began to embrace a different way of life. Giving up their nomadic existence, they settled down and started raising certain crops and domesticating several animal species. The first steps toward civilization are often described but never really examined at a deep level. What compelled them to change abruptly? It is more problematic to explain than we have been led to believe.

The first issue is very basic and straightforward. Stone Age people did not eat grains, and grains are the basis of agriculture and the diet of civilization. Their diet consisted of lean wild meats and fresh wild greens and fruits.

To begin with, we will be looking at the evolutionary discordance from a general standpoint by examining the mismatch between characteristics of foods eaten since the “agricultural revolution” that began 10,000 years ago and our genus’s prior two-million-year history as hunter-gatherers. The present-day edible grass seeds simply would have been unavailable to most of mankind until after their domestication because of their limited geographic distribution. Consequently, the human genome is most ideally adapted to those foods that were available to pre-agricultural man.

This presents us with an enigma that is every bit as difficult to penetrate as the building of the Great Pyramid. How and why did our ancestors make this leap? As they had little to no experience with wild grains, how did they know what to do to process them, or even that they were indeed edible?

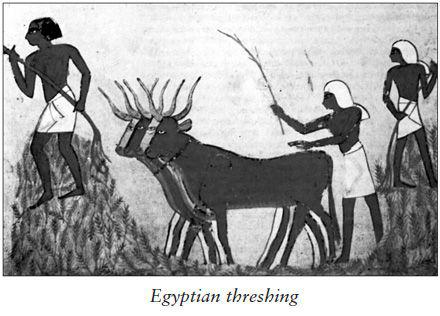

Beyond that, by the time of the abrupt appearance of the Sumerian and Egyptian civilizations, grains had already been hybridized, which demands a high degree of knowledge about and experience with plants, as well as time. If you have any experience with wild plants or fruits, or any experience of farming, then you know that wild breeds are very different from hybridized cultivars. It is well established that hunter-gatherers had no experience with plant breeding or animal domestication, and it should have taken much longer to go from zero to an advanced state than historians insist it did.

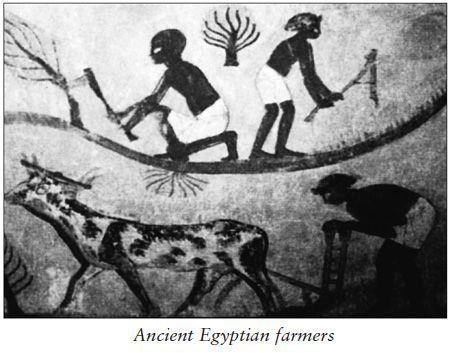

We must ask, Where did their knowledge originate? How did Stone Age man suddenly acquire the skills to domesticate plants and animals and do it with a high degree of effectiveness? We find purebred dog species like salukis and greyhounds in Egyptian and Sumerian art: How were they bred so quickly from wolves?

The following issues make the conventional explanations difficult to support: 1) mankind’s very slow process of evolution in the Stone Age; 2) the sudden creation and implementation of new tools, new foodstuffs, and new social forms that lacked precedence. If early humans had eaten wild grains and experimented with hybridization for some lengthy time period and evolved in obvious developmental stages, then we could comprehend it.

But how can we accept the scenario of the Stone Age to the Great Pyramid of Giza?

Plant breeding is an exacting science and we know it was being done in Sumeria, in Egypt, and by the ancient Israelites. If you doubt that statement, consider that we are growing the same primary grain crops that were developed by the ancients. That is a strange fact and it begs close scrutiny. There are hundreds of other possible wild plants that could be domesticated. Why have we not developed new grains from the other wild species of the past three thousand years? How could they pick the best crops with the extremely meager knowledge that they would have possessed had they just emerged from the Stone Age?

They not only figured out all these complex issues, but they also quickly discovered the principles of making secondary products out of cereals. The Sumerians were making bread and beer five thousand years ago and yet their very close ancestors—at least according to anthropologists—knew nothing of these things and lived by picking plants and killing wild beasts. It is almost as if they were given a set of instructions by someone who had already developed these things. But it could not have been from their ancestors, because they were hunters and plant collectors.

It is very difficult to reconstruct these rapid-fire transitions, especially when they were accompanied by radical changes in every other feature of human life. How and why did humans who had known nothing but a nomadic existence and an egalitarian social structure so quickly and so radically change? What compelled them to build cities and create highly stratified civilizations when they knew nothing about such organizations?