Forbidden History: Prehistoric Technologies, Extraterrestrial Intervention, and the Suppressed Origins of Civilization (30 page)

Authors: J. Douglas Kenyon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Fringe Science, #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #Ancient Aliens, #History

30

An Engineer in Egypt

Did the Ancient Egyptians Possess Toolmaking Skills Comparable to Those of the Space Age?

Christopher Dunn

W

ithin the past three years, artifacts established as icons of ancient Egyptian study have developed a new aura. There are suggestions of controversy, cover-ups, and conspiracy to squelch or ignore data that promises to shatter conventional academic thinking regarding prehistoric society. A powerful movement is intent on restoring to the world a heritage that has been partly destroyed and undeniably misunderstood. This movement consists of specialists in various fields who, in the face of fierce opposition from Egyptologists, are cooperating with each other to effect changes in our beliefs of prehistory.

The opposition by Egyptologists is like the last gasp of a dying man. In the face of expert analysis, they are striving to protect their cozy tenures by arguing engineering subtleties that make no sense whatsoever. In a recent interview, an Egyptologist ridiculed theorists who present different views of the pyramids, claiming their ideas are the product of overactive imaginations stimulated by the consumption of beer. Hmmm.

By way of challenging such conventional theories, for decades there has been an undercurrent of speculation that the pyramid builders were highly advanced in their technology. Attempts to build pyramids using the orthodox methods attributed to the ancient Egyptians have fallen pitifully short. The Great Pyramid is 483 feet high and houses seventy-ton pieces of granite lifted to a level of 175 feet. Theorists have struggled with stones weighing from up to two tons to a height of a few feet.

One wonders if these were attempts to prove that primitive methods are capable of building the Egyptian pyramids—or the opposite? Attempts to execute such conventional theories have not revealed the theories to be correct! Do we need to revise the theory, or will we continue to educate our young with erroneous data?

In August 1984 I published an article in

Analog

magazine entitled “Advanced Machining in Ancient Egypt,” based on

Pyramids and Temple of Gizeh,

by Sir William Flinders Petrie (the world’s first Egyptologist), published in 1883. Since that article’s publication, I have been fortunate enough to visit Egypt twice. On each occasion I left Egypt with more respect for the industry of the ancient pyramid builders—an industry, by the way, whose technology does not exist anywhere in the world today.

In 1986, I visited the Cairo Museum and gave a copy of my article, and a business card, to its director. He thanked me kindly, then threw my offering into a drawer with sundry other stuff and turned away. Another Egyptologist led me to the “tool room” to educate me in the methods of the ancient masons by showing me a few tool cases that housed primitive copper implements.

I asked my host about the cutting of granite, as this was the focus of my article. He explained how a slot was cut in the granite, and wooden wedges—soaked with water—would then be inserted. The wood swelled, creating pressure that split the rock. This still did not explain how copper implements were able to cut granite, but he was so enthusiastic with his dissertation, I chose not to interrupt.

I was musing over a statement made by the Egyptologist Dr. I. E. S. Edwards in

Ancient Egyptt

. Edwards said that to cut the granite, “axes and chisels were made of copper hardened by hammering.”

This is like saying, “To cut this aluminum saucepan, they fashioned their knives out of butter”!

My host animatedly walked me over to a nearby travel agent, encouraging me to buy plane tickets to Aswan, “where,” he said, “the evidence is clear. You must see the quarry marks there and the unfinished obelisk.” Dutifully, I bought the tickets and arrived at Aswan the next day.

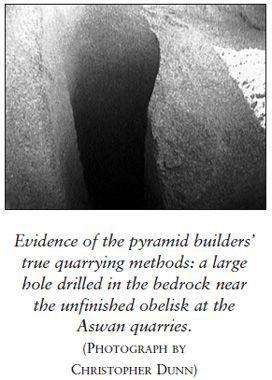

The Aswan quarries were educational. The obelisk weighs approximately 440 tons. However, the quarry marks I saw there did not satisfy me as being the only means by which the pyramid builders quarried their rock. Located in a channel that runs the length of the obelisk is a large hole drilled into the bedrock hillside, measuring approximately twelve inches in diameter and three feet deep. The hole was drilled at an angle, with the top intruding into the channel space.

The ancients must have used drills to remove material from the perimeter of the obelisk, knocked out the webs between the holes, and then removed the cusps. While strolling around the Giza plateau later, I started to question the quarry marks at Aswan even more. (I also questioned why the Egyptologist had deemed it necessary that I fly to Aswan to look at them.) I was to the south of the second pyramid when I found an abundance of quarry marks of a similar nature. The granite-casing stones, which had sheathed the second pyramid, were stripped off and lying around the base in various stages of destruction. Typical to all of the granite stones worked on were the same quarry marks that I had seen at Aswan earlier in the week.

This discovery confirmed my suspicion of the validity of Egyptologists’ theories on the ancient pyramid builders’ quarrying methods. If these quarry marks distinctively identify the people who created the pyramids, why would they engage in such a tremendous amount of extremely difficult work only to destroy their work after having completed it? It seems to me that these kinds of quarry marks were from a later period of time and were created by people who were interested only in obtaining granite, without caring where they got it from.

One can see demonstrations of primitive stonecutting in Egypt if one goes to Saqqara. Being alerted to the presence of tourists, workers will start chipping away at limestone blocks. It doesn’t surprise me that they choose limestone for their demonstration, for it is a soft, sedimentary rock and can be easily worked. However, one won’t find any workers plowing through granite, an extremely hard igneous rock made up of feldspar and quartz. Any attempt at creating granite, diorite, and basalt artifacts on the same scale as the ancients but using primitive methods would meet with utter and complete failure.

Those Egyptologists who know that work-hardened copper will not cut granite have dreamed up a different method. They propose that the ancients used small round diorite balls (another extremely hard igneous rock) with which they “bashed” the granite.

How could anyone who has been to Egypt and seen the wonderful intricately detailed hieroglyphs cut with amazing precision in granite and diorite statues, which tower fifteen feet above an average man, propose that this work was done by bashing the granite with a round ball? The hieroglyphs are amazingly precise, with grooves that are square and deeper than they are wide. They follow precise contours and some have grooves that run parallel to each other, with only a .030-inch-wide wall between the grooves.

Sir William Flinders Petrie remarked that the grooves could have been cut only with a special tool that was capable of plowing cleanly through the granite without splintering the rock. Bashing with small balls never entered Petrie’s mind. But, then, Petrie was a surveyor whose father was an engineer. Failing to come up with a method that would satisfy the evidence, Petrie had to leave the subject open.

We would be hard-pressed to produce many of these artifacts today, even using our advanced methods of manufacturing. The tools displayed as instruments for the creation of these incredible artifacts are physically incapable of coming even close to reproducing many of the artifacts in question. Along with the enormous task of quarrying, cutting, and erecting the Great Pyramid and its neighbors, thousands of tons of hard igneous rock, such as granite and diorite, were carved with extreme proficiency and accuracy. After standing in awe before these engineering marvels and then being shown a paltry collection of copper implements in the tool case at the Cairo Museum, one comes away with a sense of frustration, futility, and wonder.

Sir William Flinders Petrie recognized that these tools were insufficient. He admitted it in his book

Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh

and expressed amazement and stupefaction regarding the methods the ancient Egyptians used to cut hard igneous rocks, crediting them with methods that “we are only now coming to understand.” So why do modern Egyptologists identify this work with a few primitive copper instruments and small round balls? It makes no sense whatsoever!

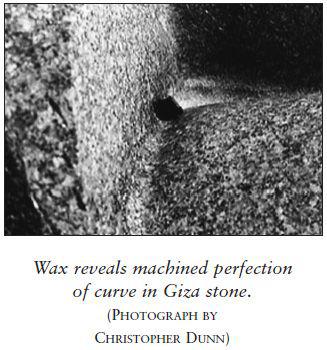

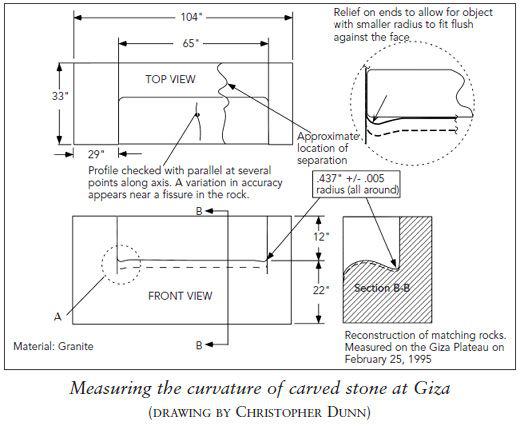

While browsing through the Cairo Museum, I found evidence of lathe turning on a large scale. A sarcophagus lid had distinctive indications. Its radius terminated with a blend radius at shoulders on both ends. The tool marks near these corner radii are the same as those I have witnessed on objects that have an intermittent cut.

Petrie also studied the sawing methods of the pyramid builders. He concluded that their saws must have been at least nine feet long. Again, there are subtle indications of modern sawing methods on the artifacts Petrie was studying. The sarcophagus in the King’s Chamber inside the Great Pyramid has saw marks on the north end that are identical to saw marks I’ve seen on modern granite artifacts.

The artifacts representing tubular drilling, studied by Petrie, are the most clearly astounding and conclusive evidence yet presented to identify, with little doubt, the knowledge and technology in existence in prehistory. The ancient pyramid builders used a technique for drilling holes that is commonly known as trepanning.

This technique leaves a central core and is an efficient means of hole making. For holes that didn’t go all the way through the material, the craftsmen would reach a desired depth and then break the core out of the hole. It was not just the holes that Petrie was studying, but also the cores cast aside by the masons who had done some trepanning. Regarding tool marks that left a spiral groove on a core taken out of a hole drilled into a piece of granite, he wrote, “[T]he spiral of the cut sinks .100 inch in the circumference of six inches, or one in sixty, a rate of plowing out of the quartz and feldspar which is astonishing.”

For drilling these holes, there is only one method that satisfies the evidence. Without any thought to the time in history when these artifacts were produced, analysis of the evidence clearly points to ultrasonic machining. This is the method that I proposed in my article in 1984, and so far no one has been able to disprove it.

In 1994 I sent a copy of the article to Robert Bauval (author of

The Orion Mystery: Unlocking the Secrets of the Pyramids

), who then passed it on to Graham Hancock (author of

Fingerprints of the Gods: The Evidence of Earth’s Lost Civilization

). After a series of conversations with Hancock, I was invited to Egypt to participate in a documentary with him, Bauval, and John Anthony West. On February 22, 1995, at 9:00 A.M., I had my first experience of being “on camera.”