Forbidden History: Prehistoric Technologies, Extraterrestrial Intervention, and the Suppressed Origins of Civilization (33 page)

Authors: J. Douglas Kenyon

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Fringe Science, #Alternative History, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Archaeology, #Ancient Aliens, #History

I’m not disputing that this is a viable means of creating a box and, indeed, there is evidence at Memphis near Saqqara that some boxes were created in this manner. These boxes had large corner radii, which were extremely rough and tapered toward the bottom—exactly what one would expect to produce using a stone ball. However, as Hawass was wielding his eight-inch-diameter ball in front of the cameras, my attention was focused on the shiny, black, so-called sarcophagus behind him, which sat in mute contradiction to his proposition.

The inside of this box had the same appearance as the box inside Khafre’s pyramid. The surfaces appeared smooth and precise but, more important, the inside corners were equally as sharp as what I had witnessed in Khafre’s pyramid. Just looking at it, one could see that to create such an artifact with an eight-inch-diameter ball would be impossible!

Likewise, creating the corner radius of the box inside Khafre’s pyramid using such primitive methods would be impossible. Checking this corner radius with my radius gauges, I started with a half-inch radius gauge and kept working my way down in size until the correct one had inadvertently been selected. The inside corner radius of the box inside Khafre’s pyramid checked

3

/

32

inch. The radius at the bottom, where the floor of the box met the wall, checked

7

/

16

inch. It should go without saying that one cannot fit an eight-inch ball into a corner with a

3

/

32

radius, or even a one-inch radius.

THE GIZA POWER PLANT: THE PROOF

I don’t think I have ever been as surprised as I was while filming inside the grand gallery. Filming inside the grand gallery had been especially rewarding, as I had had my doubts as to whether I would even get to go into the Great Pyramid. It had been closed to visitors, ostensibly for restoration, and we had spent almost a week of uncertainty over access. But after numerous calls and visits to officials, we finally got the go-ahead.

While most of the group meditated in the King’s Chamber, the video crew and I went out into the grand gallery to do some filming. I was going to describe, on camera, my theory about the function of the grand gallery. This involved pointing out the slots in the gallery side ramps, the corbeled walls, and the ratchet-style ceiling. Equipped with a microphone, I stood just below the great step, the camera at the top. While the soundman adjusted his gear, I scanned the wall with my flashlight. It was then I noticed that the first corbeled ledge had some scorch marks underneath it, and that some of the stone was broken away. Then, as the camera lights came on, things became really interesting.

In all the literature I had read, the grand gallery was described as being constructed of limestone. But here I was looking at

granite

! I noted a transition point farther down the gallery where the rock changed from limestone to granite. I scanned the ceiling and saw, instead of the rough, crumbling limestone one sees when first entering the gallery, what appeared to be, from twenty-eight feet below, smooth, highly polished granite. This was of great significance to me. It made sense that the material closer to the power center would be constructed of a material that was more resistant to heat!

I then paid closer attention to the scorch marks on the walls. There was heavy heat damage underneath each of the corbeled layers, for a distance of about twelve inches, and it seemed as though the damage was concentrated in the center of the burn marks. Then, visually, I took a straight line through the center of each scorch mark and projected it down toward the gallery ramp. That was when chills ran down my spine and the hair stood out on my neck. The line extended in alignment with the slot in the ramp!

In

The Giza Power Plant,

I had theorized that harmonic resonators were housed in these slots and were oriented vertically toward the ceiling. I had also theorized that there was a hydrogen explosion inside the King’s Chamber that had shut down the power plant’s operation. This explosion explained many other unusual effects that have been noted inside the Great Pyramid in the past, and I had surmised that the explosion had also destroyed the resonators inside the grand gallery in a terrible fire.

Only with the powerful lights of the video camera did the evidence become clear, and illuminated before me, as at no other time before—the charred evidence to support my theory. This was evidence that I had not even been looking for!

Even as I conclude this article, I continue to receive confirmation that I’m on the right track. Others are stepping forward with their own research along the same lines. A more complete update on all of this, though, will have to wait for another time. Perhaps when the Egyptian government discloses what it finds behind Gantenbrink’s door? I am most anxious to know what is discovered behind this so-called door. If my own prediction is correct, then yet another aspect of the power plant theory will be confirmed.

It has been an interesting year.

33

Petrie on Trial

Have Arguments for Advanced Ancient Machining Made by the Great Nineteenth-Century Egyptologist Sir William Flinders Petrie Been Disproved? Christopher Dunn Takes On the Debunkers

Christopher Dunn

I

f there is one area of research into ancient civilizations that proves the technological prowess of a superior prehistoric society, the study of the technical requirements necessary to produce many granite artifacts found in Egypt is it.

My own research into how many of these artifacts were produced started in 1977, and my article

Advanced Machining in Ancient Egypt

was first published in

Analog

magazine in 1984. It was later expanded to fill two chapters in my book

The Giza Power Plant: Technologies of Ancient Egypt

.

As this body of work became more popular and well known, it was only a matter of time before the orthodox camp attempted to diminish the significance of the artifacts and thereby discredit my work.

Albeit ineffectual, this they have done in both subtle and obvious ways:

- Documentaries have been produced that attempt to reinforce Egyptologists’ views that bashing granite with hard stone balls produced fabulous granite artifacts.

- A stonemason named Denys Stocks was taken to Egypt to demonstrate how the use of copper and sand, along with a tremendous amount of manual effort, can produce holes and slots in granite. This he succeeded in doing, much to the satisfaction of orthodox believers.

- Two authors who claimed to be onetime supporters of alternate ideas such as mine switched camps and wrote a book entitled

Giza: The Truth

. Though unschooled in the mechanical arts, Ian Lawton and Chris Ogilvie-Herald were determined to take an antagonistic approach to the ideas I have presented and to support the orthodox view.

In each of the above cases, the limited perspective and incomplete analysis of all the evidence, though probably passing muster with their own peer reviews, do not pass muster with my own peers, who consist of technologists involved in such work today. In fact, the consensus among the latter group is that the former are dead wrong. However, none of us is perfect, and everyone has his Achilles’ heel.

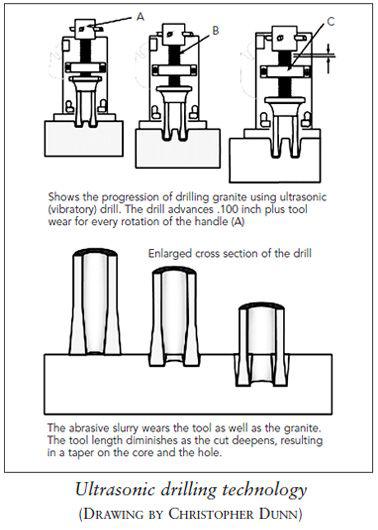

In retrospect, I will admit to having probably taken my analysis too far when I proposed that ultrasonic machining produced the artifact known as Core #7. My theory of ultrasonic machining was based on Sir William Flinders Petrie’s book

Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh.

In this book, Petrie described an artifact with marks of a drilling process that left a spiral groove in granite indicating that the drill sank into the granite at .100 inch per revolution of the drill.

My conviction was shaken when I read, in

Giza: The Truth,

that two researchers, John Reid and Harry Brownlee, had effectively dismissed my theories of how the ancient Egyptians had drilled granite. After a physical examination of this artifact, they testified that the grooves were not spiral grooves but individual rings, and were common to cores found in any modern quarry in England. A photograph of this core in

Giza: The Truth

was positioned in a way that seemed to support their contention; however, I was unable to disprove them because I had not even been in the same room as the core, let alone physically examined it.

Until I had the opportunity to perform a detailed inspection of the piece, which requires more than mere visual scrutiny, I was forced to defer to the observations of Reid and Brownlee. Nevertheless, even in so doing, if they were basing their observations on the photograph in

Giza: The Truth,

I had questions about those observations. What we have is a photograph that shows the frustrum of a cone (Core #7) with grooves cut into it. After reading this report, I immediately posted, to my Web site, a statement to the effect that I suspended any assertions I have made about ultrasonic machining of these holes and cores and I also asserted that I was prepared to examine the core for myself.

On November 10, 1999, I flew out of Indianapolis heading for England. My Webmaster, Nick Annies, had arranged, with the Petrie Museum, for the inspection of the core while the museum was closed for academic research. Nick and I took the train to King’s Cross on Monday, November 15, 1999. A short walk to the University College, London, found us, at 10:30 A.M., standing on the bottom step of the Petrie Museum, looking up at a gregarious doorman who advised us to have a cup of tea while we waited for the museum to open and then pointed us in the direction of a cafeteria. Not only a cuppa did we find there, but a wonderful English breakfast as well!

Then it came time to inspect the infamous Core #7. Although I had talked and written about this core for more than fifteen years, this was not the reverent visit to a holy relic that one might expect. I was not especially breathless with excitement to take the artifact into my latex-gloved hands. Nor was I impressed with its size or character. To tell the truth, I was profoundly unmoved and disappointed. With the old Peggy Lee song “Is That All There Is?” bouncing around in my head, I peered at this insignificant-looking piece of rock that had fueled such a heated debate on the Internet and in living rooms and pubs across the globe.

I was thinking to myself as I looked at the rough grooves on its surface, “How do I make sense of this?” And, “What was Petrie thinking about?” I looked up at Nick Annies standing over me. He had a look on his face that reminded me of my mother, within whose face I sought comfort when, at the age of eight, I was lying on the operating table having a wart burned out of my palm by a long, hot needle.

Not a word passed between us as I formulated my ultimate confession to the world. I had made a huge mistake in trusting Petrie’s writings! The core appeared to be exactly as Reid and Brownlee had described it! The grooves did

not

appear to have any remote resemblance to what Petrie had described. With the truth resting where a wart once grew, I was frozen in time.

With resignation I proceeded to check the width between the grooves using a 50X handheld microscope with .001 gradated reticle to .100 inch. At this point, I was certain that Petrie had been totally wrong in his evaluation of the piece. The distance between the grooves, which are scoured into the core along the entire length, was .040–.080 inch. I was devastated that Petrie had even gotten the distance between the grooves wrong! Any further measurements, I thought, would just be perfunctory. I couldn’t support any theory of advanced machining if Petrie’s dimensions of .100 inch feed-rate could not be verified! Nevertheless, I continued with my examination.

The crystalline structure of the core under microscope was beyond my ability to evaluate. I could not determine, as surely as Petrie had, that the groove ran deeper through the quartz than through the feldspar. I did notice that there were some regions, very few, where the biotite (black mica) appeared to be ripped from the felspar in a way that is similar to other artifacts found in Egypt. However, the groove passed through other areas quite cleanly without any such ripping effect, though again I support Brownlee’s assertions that a cutting force against the material could rip the crystals from the felspar substrate.

I then measured the depth of the groove. To accomplish this I used an indicator depth gauge with a fine point to enable it to reach into a narrow space. The gauge operated so as to allow a zero setting when the gauge was set on a flat surface without any deviations. When the gauge passed over a depression (or groove) in a surface, the spring-loaded indicator point pushed into the groove, causing the needle to move on the gauge dial, indicating the precise depth.

The depths of the grooves were .002 and .005 inch. (Actually, because there were clearly discontinuities in the groove at some locations around the core, the actual measurement would be between .000 and .005 inch.)

Then came the great question. Was the groove a helix or a horizontal ring around the core? I had deferred to Reid and Brownlee’s assertions that they were horizontal and I was, at this juncture, painfully assured that it was the correct thing to do. It was Petrie’s description of the helical groove that made Core #7 stand apart from modern cores. It was one of the principal characteristics upon which I had based my theory of ultrasonic machining. But what I held in my hand seemed to support Reid and Brownlee’s objections to this theory, for they said that the core had an appearance similar to any other core one may produce in a quarry.

White cotton thread was the perfect tool to use when inspecting for a helical groove. Why not use a thread to check a thread! I carefully placed one end of the thread in a groove while Nick secured it with a piece of Scotch tape. While I peered through my 10X Optivisor, I rotated the core in my left hand, making sure the thread stayed in the groove with my right. The groove varied in depth as it circled the core, and at some points there was just a faint scratch that I would probably not have detected with my naked eye. As the other end of the thread came into view, I could see that what Petrie had described about this core was not quite correct.

Petrie had described a single helical groove that had a pitch of .100 inch. What I was looking at was

not

a single helical groove, but

two

helical grooves. The thread wound around the core following the groove until it lay approximately .110 inch above the start of the thread. Amazingly, though, there was

another

groove that nestled neatly in between!

I repeated the test at six or seven different locations on the core, with the same results. The grooves were cut clockwise, looking down the small end to the large—which would be from top to bottom. In uniformity, the grooves were as deep at the top of the core as they were at the bottom. They were also as uniform in pitch at the top and bottom, with sections of the groove clearly seen right to the point where the core granite was broken out of the hole.

These are

not

horizontal striations or rings as trumpeted in

Giza: The Truth,

but rather helical grooves that spiraled down the core like a double-start thread.

To replicate this core, therefore, the drilling method should produce the following: