Forgotten Voices of the Somme

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

Table of Contents

- Title

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Author's Preface

- Introduction by Professor Richard Holmes

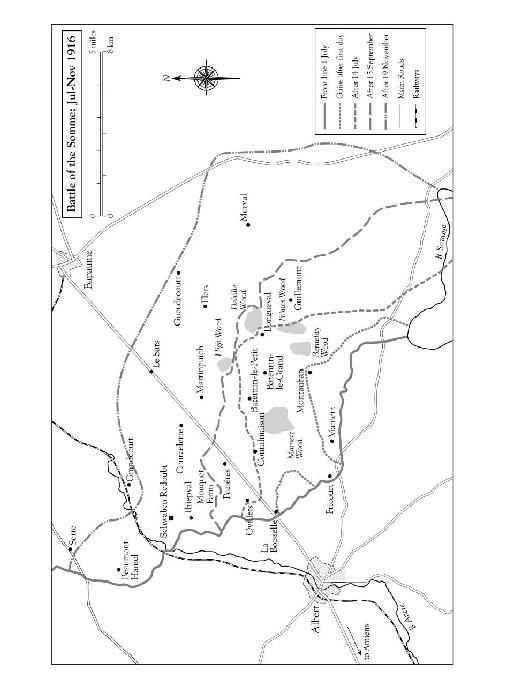

- Battle of the Somme: Jul–Nov 1916

- Young Lions

- Into the Trenches

- Verdun

- Cometh the Hour

- July 1, 1916

- Out of the Trenches

- The Fight Goes On

- Looking Back

- Index of Contributors

- General Index

FORGOTTEN

VOICES

To the Men who fought on the Somme between July and November 1916.

I, that on my familiar hill

Saw with uncomprehending eyes

A hundred of Thy sunsets spill

Their fresh and sanguine sacrifice,

Ere the sun swings his noonday sword

Must say goodbye to all of this:–

By all delights that I shall miss,

Help me to die, O Lord.

Lieutenant William Noel Hodgson, MC

9th Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

(January 3, 1893 – July 1, 1916)

FORGOTTEN

VOICES

OF THE

SOMME

THE MOST DEVASTATING BATTLE OF THE GREAT WAR

IN THE WORDS OF THOSE WHO SURVIVED

IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM

JOSHUA LEVINE

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407025520

Version 1.0

Published in 2008 by Ebury Press, an imprint of Ebury Publishing

A Random House Group Company

Text © Joshua Levine and Imperial War Museum 2008

Photographs © Imperial War Museum 2008

Joshua Levine has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781407025520

Version 1.0

To buy books by your favourite authors and register for offers visit www.rbooks.co.uk

Acknowledgements

Once again, I would like to thank everybody at the Imperial War Museum Sound Archive, Photography Archive and Photo Studio. Margaret Brooks, Peter Hart, Richard McDonough, John Stopford-Pickering and Richard Hughes have all been generous with their time and their knowledge. Their infectious enthusiasm for the treasures that they hold in their collection fills me with admiration.

I would also like to thank Liz Bowers, Terry Charman, Abigail Ratcliffe, Madeleine James, Ken Barlow, Jake Lingwood, Jim Gill, Barbara Levy, Alan Wakefield, Ian Procter, Dave Parry, Andrew Margerison, Jason Strange and Kiran Patel. My thanks also to Max Arthur, Sam Crew and Claire Price.

Most of all, I pay my respects to the men who raided, dug, wired, advanced and died ninety-two years ago in Picardy.

Joshua Levine, June 2008

Author's Preface

The influence of the Battle of the Somme on the psychology of subsequent generations has been so great that it now invites trite modern comparisons. It has become a lazy way of alluding to fear, danger or horror. I once sat listening to an actor as he described the courage necessary when stepping out on stage in front of a packed audience. 'It must be rather like,' he said, 'going over the top at the Somme.' Or perhaps not. Perhaps going over the top was nothing at all like appearing in weekly rep, but was, rather, an experience that can only be described by the men who did it: the men whose voices appear in this book.

This is a book about individuals, and individual experiences. These men are not historians. They are not generally interested in conclusions, nor do they seek out the 'bigger picture'. Occasionally, they question the ethics of an action, sometimes they challenge the judgement of those higher up the chain of command, but, for the most part, they tell us about what they – and they alone – did at a time when the rules of civilisation were suspended. The Battle of the Somme threw hundreds of thousands of men into a world beyond morality and this book is a record of their reactions. These reactions can – and should – be used in evidence when framing conclusions. Nevertheless, these men are entitled to stand alone as witnesses to an event that is difficult for us to imagine truly.

This book is dedicated to the men who fought on the Somme, those who lived and those who died. They were asked to make sacrifices that we can barely comprehend in our modern, rights-driven society. It is the least that we can do to read their stories, and try to understand why, and how, they did what they did.

Joshua Levine, June 2008

Introduction by

Professor Richard Holmes

There is an ineluctable poignancy to the battlefield of the Somme, although time has healed most of the damage that man inflicted on this rolling downland. Those little villages that meant so much in 1916 have reverted to somnolent type; broadleaved trees have replaced their shattered predecessors in big woods like Mametz and Delville, and the Albert-Bapaume road still slashes busily across the battlefield. The Somme meanders its gentle way just south of the British sector, and its tributary, the little Ancre, curls in behind the old front line just west of the Thiepval ridge, crowned by the memorial listing over 70,000 men missing on the Somme between the arrival of the British Third Army in the sector in July 1915 and March 20, 1918, the eve of the great German offensive.

The visitor to the Somme needs real determination not to have his interest wholly fixed by the cemeteries and

memorials

scattered across these haunted acres, for they help chart the impact of the most costly battle in British history. Its first day was the army's bloodiest, and the total of 415,000 British casualties – to which must be added the 200,000 French and upwards of 600,000 German – make it one of the deadliest battles in world history. However, the memorials post-date the battle, and it is all too easy to let them detract from the militarily crucial details of the landscape (a gentle declivity here, a concave slope there) which meant so much to men who lived and died upon it. What matters is less the view

from

Thiepval memorial than the view

of

Thiepval ridge from the uplands across the Ancre, whence British artillery observers did their best to batter German trenches before the first attack on July 1, 1916. To understand the microterrain of the Somme we must, in our mind's eye, strip the landscape of precisely those symbols which give it such an enduring appeal.

In very much the same way it is easy to study the Somme through the thick prism of hindsight, and to superimpose our own view on its events, just as we have planted our own memorials on the landscape upon which it was fought. The great strength of this remarkable book is that it tells the story of the Somme in the words not of professional historians, but of the men who fought the battle. These men came from a world in which 'you could get nicely drunk on a shilling', farm work went on from 'four o'clock in the morning to seven o'clock at night', many families got through the week by pawning belongings on Monday mornings, and village policemen spanked naughty boys. Many young men were 'full of patriotism and the

Boy's Own Paper

', and came from a background where they had had 'a certain amount of discipline' so that army life was less of a shock. Several of the 'Pals' battalions, formed in response to Lord Kitchener's appeal for volunteers in August 1914, were filled with 'a splendid lot of men . . . university students, doctors, dentists, opticians, solicitors, accountants, bank officials, works directors, schoolmasters, shop owners, town hall staff, post office staff – you name it'.

Neither patriotism nor the strong bonds forged within units made men immune to the shocks of war. One was struck by seeing a convoy of wounded leaving Rouen as he arrived, and another saw 'a mangled body blown to bits on a sack' on his first trip to the front, and a third remembered the jam-like consistency of the French corpses that made up the rear wall of his trench. Some remembered the weight they carried in battle – 'I could have been a mule . . . not a human being' – and others the sheer impatience – 'browned off with the waiting' – of wanting to get on with the attack. One officer suggested that most people had a breaking point, although there were a few actually who '

liked

it'. An experienced private went to the heart of the matter when he affirmed that: 'Bravery is shown when a man is fearful but continues to carry out his obligations . . . Fear becomes cowardice when one withdraws oneself from one's moral obligations.' However, even the well-motivated might relish a wound serious enough to get him home, 'a Blighty one', in the jargon of the day.

Too many accounts of the battle focus largely on its first day, but the accounts here take us across the knife-edge of that terrible summer, from the mid-July attack on Bazentin Ridge, through the first tank attack on September 15, to the final autumn battles as the weather closed in. One officer remembered that the attack on Beaucourt on November 13, at the very end of the battle, took place in 'frightful' conditions. 'There was so much water, everywhere,' he wrote. 'I remember a broken-down railway station, shelled for months, and it was one of the most unpleasant times in my experience. The terrain was simply a mass of shell-holes.' He took about seventy men into the line, and brought out thirty-six a week later.

Men remembered the battle in many ways. One officer thought that 'people just don't want to know' about the real war, and another gruffly opined that war poets 'wrote nonsense. Writing poetry about horrors. No point. It goes without saying'. 'I didn't deserve to get through it all,' admitted a private touched by the guilt that afflicted many survivors. 'I look upon the war as an experience,' reflected another. 'I got just as much pleasure out of it, as I did the bad times. When I came back, I was no different from when I went.' In contrast, a comrade admitted that the war had never really left him. 'I can only remember faces and first names. I can remember them one after another . . . It's a thought that's in my mind all the time. Has been for years.'

This is not a book which seeks to rule off a historical balance-sheet that will always haunt us, but to let those who fought more than ninety years ago tell us about a piece of France that is for ever British.