Forgotten Voices of the Somme (5 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

12th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

Our Pals battalion was formed as a result of an appeal from the Mayor of Sheffield,

Lieutenant Colonel Branson

.

Colonel Hughes

was our first commanding officer, and by God, what a splendid lot of men he had to command. University students, doctors, dentists, opticians, solicitors, accountants, bank officials, works directors, schoolmasters, shop owners, town hall staff, post office staff – you name it. Professional men, not professional soldiers, but when they got in the trenches, they behaved like professional soldiers.

17th Battalion, Manchester Regiment

I felt it was my duty to join up. We hadn't been the ones that started the war. Before I joined up, I undertook one or two long walks, of six miles each way, thinking that as 'an army marches on its stomach', we would be required to do a lot of marching. Then, on September 1, 1914, a pal from my office and myself went down to the town hall, where we were told that they'd filled their requirements, but they were forming another battalion, and if we liked to go down the following day, we might be enrolled. So we duly went down, and we found that there were quite large numbers from the big firms in the town, like CPA and Tootals. But we were the only two representatives of our firm, and there were a lot of other little firms like us. The big firms were taken first, and they were stood in ranks and formed into companies. 'A', 'B', 'C' Companies were formed from the big firms, and then the riff-raff – as you might say – were put into 'D' Company. But a strange thing happened. We were all given the order, 'About turn!' So what would have been 'D' Company became 'A' Company; the riff-raff – like us – became 'A' Company.

12th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

Three of us made up our minds to join up at the end of August 1914. We went

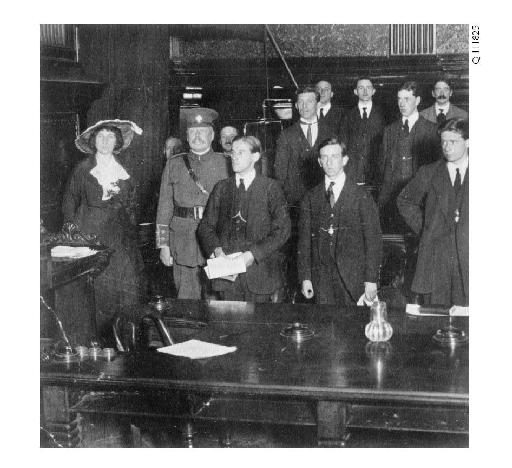

Young men enlisting with the Leeds Pals in 1914.

to the Drill Hall to join up, and there were seven hundred people outside. They were only letting in twelve men at a time. The three of us wanted to join the cavalry, even though we'd never been near a horse in our lives, but they told us there was no vacancies in the cavalry. So we asked what vacancies they had in the infantry, and they said they'd got the Notts and Derbys, at

Normington Barracks, Derby

. We could have bloody well walked there, and we wanted a long ride in a train. None of us had ever had a holiday in our lives. We wanted an adventure, and they offered us either the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry, or the

Northumberland Fusiliers

in Newcastle. We knew that Newcastle had a good football team, so we decided to join the Fusiliers.

When we got on to the barracks square at Newcastle, there were at least two thousand men standing around, tossing pennies and all that. We asked which way to go, and we were pointed towards a window at the far corner of the square. We went there, handed our papers in, they gave us a blanket – and that was that. We were on our own. All we knew in Newcastle was the railway station, and we went back down there. On the way, we clubbed together some pennies, and we bought half a pound of cheese and a loaf. In the booking hall of the station, there were sixty men walking about, just like us, with blankets over their shoulders. We thought we'd sleep that night in the booking hall, but a porter came to one of us and said that there were some empty carriages in the siding, and we could sleep there if we liked. So that was how I spent my first night in the army. Sleeping in a railway carriage.

After that, they sent us down to

Aylesbury

for a fortnight, until they found out that we should have been in

Tring

. So we were sent there, and we were trained on the

Dunstable Downs

, round Coombe Hill. We were trained in open warfare, wearing civilian clothes. The first thing that I was given was a change of underwear – long johns and a thick vest. They drove me mad, because I'd never worn underwear before in my life.

1/8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment

I joined up at

Witton barracks

in February 1915, at the back of the Aston Villa ground. At school, there was a clique of us lads who formed a football team, and when we'd finished schooling we kept the same little clique. Teddy

Deacon

and

Roger Walker

, other members of the team, joined up that day as

well. We went in, and there was a medical officer. We took our trousers down, coughed. They tested our chests, and asked our trade of calling.

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

On September 7, 1914, I walked round to New Scotland Yard, to enlist in His Majesty's Forces. They offered me the artillery, the lancers, but when I found that these played around with horses, I said, 'No thanks!' and I enlisted in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. On September 9, with two hundred others, I entrained at a London railway terminus,

en route

to

Pontefract

, to join the regimental depot. We detrained at

Wakefield

and were told there was an hour to spare, so we walked up the cobbled streets and found a fish shop, where we had a meal.

But it was a strange new world for me; there were reflections in the sky from the blast furnaces of the factories, and there were lights from the mines. There was an autumn mist, that was more like a shower of rain, dampening my clothes and making me cold. We went on to Pontefract, where we arrived at around 11.30pm, and there we found absolute chaos. Nobody had been advised that we were coming, and there were no arrangements made for our reception. Many walked the streets at night, and some went home in disgust. But more and more volunteers kept arriving, and the streets of Pontefract echoed with their footsteps, and we all added to the chaos. After two weeks, they formed the

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

. Its composition was rather unique: two companies of Yorkshiremen, one of Welshmen and one of Londoners. At last, we felt that some order had been made out of chaos, and soon we would be on our way to France.

Private Basil Farrer

3rd Battalion, Green Howards

I wouldn't say we (as regular soldiers) ridiculed the Territorials, but we did refer to them as 'Saturday night soldiers'. We thought they were amateurs. They were a selective crew, and they were enthusiastic, but we as professionals thought ourselves superior. Naturally. We were serving soldiers, and when we went out to France, we were doing the job we were trained to do. Some of the men had done the South African War, and knew what war was about. We were going out to fight – I didn't care if it was the French or the Germans.

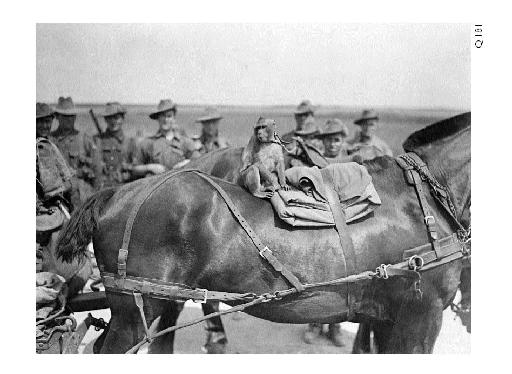

Lions led by monkeys; an Australian mascot on the Somme.

We had been instilled in our regimental history, and the glory of it, and you didn't know the carnage until you met it. So at the beginning we were really enthusiastic. We thought ourselves very superior too. The British soldier

did

think himself superior to any continental soldier.

We were issued with a leaflet that Kitchener had printed. It was Kitchener's advice, to remember we were British soldiers, and how to act, and that we were ambassadors representing our country. At the time I took no notice. I was too young to bother. I just read it and that was all. In parts, it read like a parson's advice to a party going off on a weekend binge to Paris. It referred to the temptations of wine and women. The ordinary soldier didn't expect to find wine and women. Kitchener might have been used to that kind of thing in

Egypt

, but we were not going to Egypt. We were going out to fight. There was not much hope of women and wine – or temptations, in any event. Kitchener could have been more inspiring to the troops going out.

Into the Trenches

I saw a mangled body blown to bits on a sack. I was scared stiff.

The majority of the men who went out to France had never been abroad before. These men were to become used to a strange world of traverses, funk holes and parapets. Trenches had long been used by the British Army in wartime, but the static nature of the Great War was turning these from temporary earthworks into elaborate, semi-permanent constructions.

1st Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light

Infantry

We left

Burnham-on-Sea

and went to

Southampton

. It was two days before we went from Southampton to France, and we were allowed out from Southampton into the town, and it was my birthday. I went and got myself a bottle of whisky to celebrate. We travelled to France on an old cattle boat, and we had to wait on board while they loaded it up with horses. Eventually, as it got dusk, we left Southampton. Naturally, we were all supposed to be down below, but I had my bottle of whisky, and I didn't want to take it down below. So I crawled along the deck towards the centre and I crawled under a sheet of tarpaulin, all by myself. I lay quiet, and the boat started to 'chook, chook, chook . . .' I had a tot or two, started enjoying myself, and I fell asleep. When I woke up, the engines had all stopped, and I thought we'd arrived. I shook the tarpaulin back – it was covered with snow. One of the deck hands saw me. 'What are you doing here?' he said. 'Have we got there?' I said. 'No!' he said. 'We're back where we started. We got out of the Solent, some

U-boats

spotted us, and we turned round and came back. But we're going again in a few minutes and they're going to send an escort with us.' I asked him if he'd like a drink, and he had a good old swig out of the bottle. 'I'm frozen with cold,' I said. 'Come with me!' he said, and he took me down along the side of the boat, opened a door and led me into a small kitchen with a stove in the corner. 'You'll be lovely and warm in here,' he said, and I sat on top of the stove, and I went fast asleep again, and next thing I knew, he was shouting at me, 'Come on then! We're at

Le Havre

!'

2nd Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

The first shock I had: when we went from Southampton to Le Havre and then up the river to Rouen, we saw a convoy of wounded coming in. Thousands of them. It was my first sight of war – and it took away the glamour of what we were doing.

12th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

We could see a lot of German prisoners working on the quay at

Marseilles

as we arrived. They were singing, and grinning, as happy as can be. You could see what they were saying: these poor beggars are going up to the firing line,

but

we've finished

. We're prisoners until the end of the war.

Private Ralph Miller

1/8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment

When I got to France, there was four inches of snow on the ground, and we marched from Le Havre to

Harfleur

. It was a nasty bloody march with full pack. A slog all the way. The little French kids shouted '

Chocolat!

' at us.

4th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

As we were marching to the Somme front, we passed a paper boy. He had bundles of French newspapers under his arm, and he was shouting, '

Le Journal!

Germany buggered up!'