Forgotten Voices of the Somme (9 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

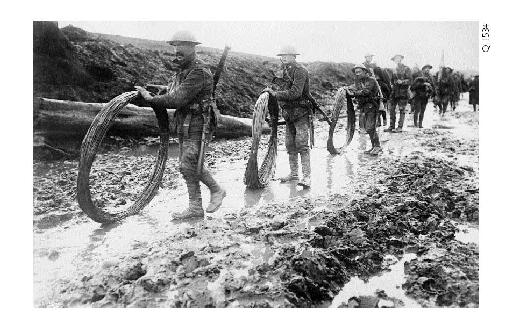

Taking wire up to the forward area.

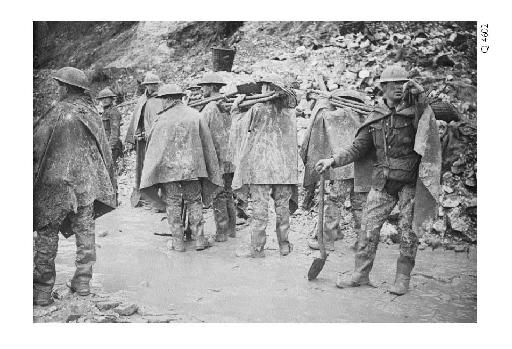

A working party ready to dig.

Private Harold Hayward

12th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment

The first time I went over wiring, we were told to go quietly, not a word to one another. We were going to make a proper continuous line. I happened to step to one side, and I fell into an old French latrine. I thought to myself, 'I am not going to die like this!' They pushed their rifles down, and I caught hold of two of them, and they pulled me out. No one would come near me for the rest of the time in the line.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

Another duty at night was to man the

listening posts

. A shallow trench would be dug from the front line out into no-man's-land – perhaps a hundred yards in front, depending on what distance the two opposing lines of trenches were. The listening party would consist of a corporal and two men, and their job was to just lay in this listening post with their head above ground level, and just watch and listen. For example, if they heard any barbed wiring going on or a German patrol they would return to the line and report it and we'd open fire on wherever this activity was.

Rifleman Robert Renwick

16th Battalion, King's Royal Rifle Corps

The listening post was a very dreary do. I went out with an officer one night, and I had an idea that the lad on the listening post was asleep. Somehow, I got in front of the officer, in case he was. And when I got there, the lad was just dozing off. I woke him up. It would have been a serious crime if he'd been found asleep.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

And at night, there'd be

trench raids

. We knew these were a waste of time, we just hated them. But some general about thirty miles behind the line wanted to know who was in the trenches opposite, and he would send up a message 'Raid and get prisoners'. He ought to have had the job himself. And you'd have artillery preparation to destroy their wire, and perhaps a whole division of artillery would put down a barrage on the German wire to smash it down,

and then they would put what they called a 'box barrage' down. Twelve guns would fire on one point of the German trench line to seal off everything from there. But by doing that you're sending an open postcard to the Germans, aren't you, that you're coming over? Oh God, the men just hated it.

Corporal Don Murray

8th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

We were supposed to go over with the sole intention of bringing a prisoner back. We had to black our faces up. As a matter of fact, we blacked ourselves up once for a raid – and it snowed like hell. On another raid, I had an officer called Morris in charge of me. Mr Morris was ever such a nice chap, but he spoke with a lisp. Instead of Morris, his name was 'Morrith'. He had a way of inspecting your rifles, and he'd say, 'There'th a thpeck of dutht down your barrel!' He was a regular figure of fun, and he was beside me, and a shot came, and went through the front of his cap, hit his cap badge and flew up. It didn't hurt him. He said, 'I'll never be killed now, Murray! Look at that!' And there was a hole from his cap badge, right through the top of his hat.

13th Battalion, York and Lancaster Regiment

If we could go out and pinch a couple of Germans, and bring them back, they were thrashed in the orderly room. I don't mean mentally thrashed, I mean physically thrashed. They would

torture

them, and they would tell them all they wanted, depending on the nature of the fellow, of course. Because some fellas spit it all out, and others try to hold it in. That was the object, getting to know who was in the line opposite us at that time, where they came from, and all that sort of thing.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

We had a very, very keen officer by the name of

Van Sommer

. It was a Dutch name but he was English all right, a very, very brave man he was, and I used to hate going out on patrol with him, because he would walk straight across noman's- land, straight up to the barbed wire, standing up all the time, and he would take a pair of snips with him and he'd take a sample, the Germans popping away at him, and bring back the sample, and he would walk away, and he expected you to do the same. I used to hate him.

A narrow escape.

Second Lieutenant W. J. Brockman

15th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

We had a very gallant fellow with us, a Jew of German extraction, name of

Mandelberg

. He was the sort of bloke who would go out into no-man's-land and explore. He went out one night, and as he came back through the wire, he was challenged by the sentry, who said, 'Who goes there?' 'Captain Mandelberg!' he replied. He'd gone too far along, over to another regiment – and the sentry shot him. Fortunately, he was only wounded, and the sentry was arrested. He was asked, 'What did you do that for? Shoot a British officer?' 'I thought he said

Hindenberg

,' he said, 'so I shot him.'

Corporal George Ashurst

1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

I went out one night with three men, on a patrol to find out if Jerry was doing anything. We went over the top, and under our wire – we were sliding along on our bellies, with bombs ready to throw, and I had a revolver. If there had been any Germans out there, it would have been a case of who got their bomb in first. Then, Jerry opened up with a machine gun. It was a fixed gun, so you had a chance. He used to skim his bullets along the top of the trench – a foot above the top. If you could lie below that foot, you were safe – even if it was only just missing you. The three men with me had never been out before at night, and, in between these machine-gun spurts, I said: 'Lie flat! Let the bullets go over you! Keep flat down!'

1st Battalion, Leicestershire Regiment

Trench raids is why '

trench clubs

' came into being. When I came home on leave, my dad was a bit on the religious side, and he said it weren't right that human beings should use cudgels on other human beings. I am sorry to say the one that is on display in the

Imperial War Museum

has actually been used. That was my one.

2nd Battalion, Cameron Highlanders

I joined a party that was going out at night, staying out all the next day and not coming back until the next night. That was a ghastly experience. We

were not able to move during the day. We were in a shell-hole, where we partly covered ourselves with camouflage, and we were listening – trying to find out exactly what was happening. When we were coming back in, they put up Very lights, and they found us, and opened up on us. Those that didn't get hit straight away got into shell-holes, and in due course we decided that we'd take a chance on getting in. I made a run for it. I was getting through the barbed wire when my right foot went dead. When I got into the trench, I discovered that a bullet had gone right through without touching any bone, tendon, or anything.

Sergeant Charles Quinnell

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

As you looked over your trench through your periscope, all you could see was the devastated land of no-man's-land, and the German barbed wire, and you never saw a sign of life. It was one of the most desolate sights in the world. And yet you knew, very well, that within shouting range there were hundreds and hundreds of men.

Corporal George Ashurst

1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers

There was always sniping. Every minute of the day and night there was sniping. We suffered a lot of casualties from it. There were no precautions we could take – just to be careful.

Lieutenant James Pratt

1/4th Battalion Gordon Highlanders

We were trained in how to cope with German

snipers

. One way was by putting a turnip on the parapet of your trench and waiting for the sniper to hit it. He would have a go at it and make a hole. Then you put another turnip up at another point and the sniper would have another go. Then you looked through the bullet holes and that gave you a close approximation of his position.

Lieutenant William Taylor

13th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

We always had snipers on duty, and when walking along the line, I would occasionally take the sniper's position and see what he was looking for. I can

remember having a shot myself, once or twice, at what I thought was the enemy. They were a fair way away, and it was only very occasionally one caught sight of them.

Private Ralph Miller

1/8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment

When you were sniping, you set yourself a site, you saved yourself a little space, you got a good view of something and you let go. Aiming at anything that bloody moved. Sometimes, you'd strain to look at a tree trunk, and you'd see it move, and the more you stared, the more it moved, and you had to be very careful. If you let go at something like that, there might be one of their snipers, having a go at you.

9th Battalion, Devonshire Regiment

Often in the trenches, instead of a rifle, I would carry a cudgel – a stick with a piece of lead at the end – and I walked up and down. The men were spaced out, all along the trenches, and I wanted to make sure that they were doing their jobs all right.

Lieutenant William Taylor

13th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The

officers

had to enforce a certain amount of discipline. Particularly with regards to keeping rifles clean, and the men keeping themselves clean. We inspected the men's feet, because we got very wet, and unless a man changed his socks, and kept his feet moderately dry, you got trench foot, and became a casualty.

Corporal Harry Fellows

12th Battalion, Northumberland Fusiliers

The officers were mainly public schoolboys. They came through the officers' training in the public schools, and they were given commissions. They weren't taught to think. Only to lead.

Lieutenant William Taylor

13th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

The association between officers and men was so much closer in the line than on the parade ground at home. The discipline wasn't as strict, and one was so much closer to one's men, that one got to know them better. The friendship was different to what it was at home. My men were friendly with me. I knew every man's name, and I got to know more and more about them. I would talk to them in a casual way.