Forgotten Voices of the Somme (11 page)

Read Forgotten Voices of the Somme Online

Authors: Joshua Levine

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Military, #World War I

I lost some good friends. All the same, I wasn't affected. The fact of your pal falling – you had to leave him and carry on. Once, I was on duty with a man called

Harold Doubleday

, when a whizz-bang came over. Harold was hit in the shoulder by the nosecap, when I was standing beside him. I called for stretcher-bearers and left it at that. That was all that could be done.

Corporal Jim Crow

110th Brigade, Royal Field Artillery

I found out that my brother was nearby with the

Royal Welsh Fusiliers

, and I went to the captain and asked if I could go and see him. We weren't too busy just then, and he said yes, and he told me to take the bicycle. I found my brother. I hadn't seen him for seven years, and I had a few hours with him, before I went back. He wanted me to transfer into his regiment, but I wasn't prepared to do that. And seven days later, he was killed. He was in a salient, and our artillery opened a barrage up and hit him. We were told that

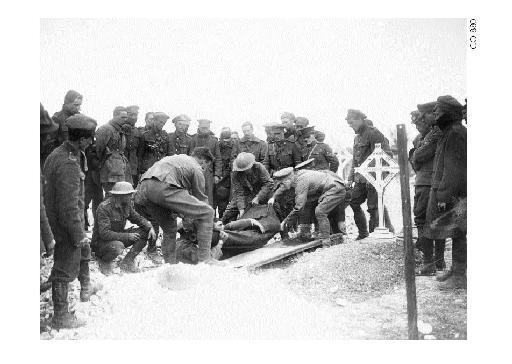

The burial of a major.

he'd been killed in action, but members of his regiment told me how he was killed.

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

My pal Tom Smith came up to me, and said, ''Ere, my young brother's out here! He ain't eighteen yet! I'm going to see the colonel about this!' Tom had bumped into his brother, and said to him, 'What the devil have you come out here for?' and his brother had said, 'I didn't know it was going to be like this!'

Lieutenant William Taylor

13th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

An officer censored the men's letters. To see that there was no mention of where we were, and that there was no defeatist talk. One didn't read it through word for word. One glanced through.

Major Murray Hill

5th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

One man wrote a letter saying to his wife: 'I hope this letter finds you as it leaves me. I've got a bit of shrapnel in my bottom.'

Private Ralph Miller

1/8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment

I bought four silk postcards to send home, and I sent one straightaway, but it was censored and destroyed. They were worried that the ship they were on would be torpedoed, and they'd give information away to the Germans. The other three, I just wrote on them 'OK, Ralph'.

Second Lieutenant Tom Adlam VC

7th Battalion, Bedfordshire Regiment

We used to get our letters at the front. I was unfortunate because I read that my dear mother had died. They applied for me to come home on leave. I went to see the adjutant. 'Well, if you go back,' he said, 'by the time you get there the funeral will be over. I advise you to stay here. You can't do any good going home.' So I stayed. And if I had gone back, I shouldn't have won the

Victoria Cross

. . .

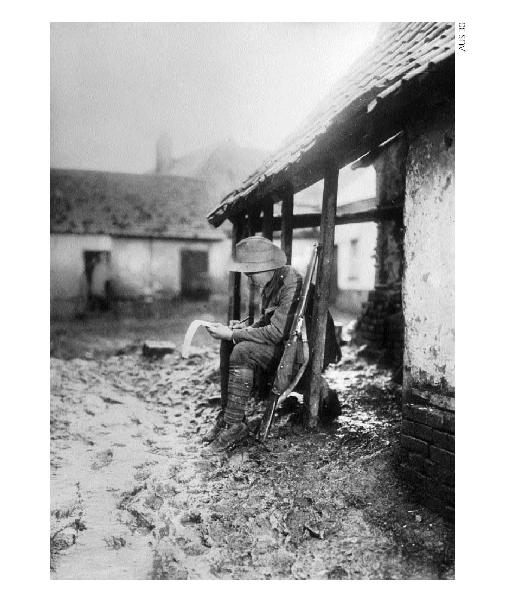

An Anzac soldier writes home.

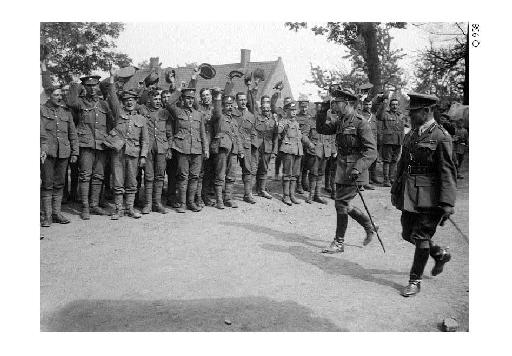

Men of the

25th Infantry Brigade

gather to welcome the King.

Private Tom Bracey

9th Battalion, Royal Fusiliers

I was mending my trousers one day. There I was, sewing them, when an orderly came along and said that

Lieutenant Van Someran

wanted to see me. I said that I'd be along as soon as I'd mended my trousers. So I went along, and the lieutenant told me to make myself as clean and tidy as I could, because eight of us were to 'go back'. He didn't say what it was all about. So I had to go behind the lines with these seven others and we slept the night, and in the morning we had to brush our boots and we were taken to a farm.

And then King George showed up – to inspect the division. So the King arrived in a car, got out, walked steadily through the ranks, spoke to one or two people, and within five minutes he was gone. We had to put our hats on our bayonets, and wave them around, and then we had to go back to rejoin our battalion. We didn't think much of all this. You ought to have heard the language . . .

Verdun

Many men had their feet frozen: some of them had to cut them off.

Just as the

Allies

were making plans for an offensive that would bring the war to an end, so too were the Germans. On February 21, 1916,

Germany

launched an attack on

Verdun

, a strongly fortified city, 150 miles south-east of the Somme. Verdun was carefully chosen as an objective by

General Falkenhayn

, the Chief of the

German General Staff

, for its symbolic significance to the French, which was out of all proportion to its strategic importance. Verdun had repeatedly offered determined resistance to German attacks down the centuries, most recently during the Franco– Prussian war of 1870. Falkenhayn expected – and hoped – that the French would defend this symbol of national pride to the very last man, giving rise to a long, bloody struggle, that would 'bleed the French Army white'. France, believed Falkenhayn, would eventually be compelled to agree to a peace on German terms, which in turn would force Britain out of the war.

In the event, the French behaved much as Falkenhayn predicted. They defended Verdun furiously, and within a month had suffered almost a hundred thousand

casualties

; within four months, half a million. The fight for Verdun had a number of far-reaching effects on the intended attack on the Somme; firstly, it gave the attack extra importance as a means of relieving the intense pressure on Verdun. Secondly, it meant that far greater responsibility for the Somme attack would now fall on the British. Thirdly, it ensured that the attack would have to be swiftly mounted, before Verdun fell, which in turn meant that Haig's hopes of a decisive breakthrough on the Somme might have to be sacrificed in favour of a more hastily prepared – and potentially far bloodier – attritional struggle.

French Artillery Observer

We arrived near to

Verdun

on February 16. It was snowing and very cold. We knew th

at someth

ing was going to happen because the Germans were directing fire on almost every French battery they had discovered, but it was very light fire – in order not to call our attention to what was going to happen. We naturally thought that we were going to enter into a very big event. Trenches were being made at the back of our first defences, that showed that we were preparing for the future.

On February 21 we were around

Douaumont

, in the very close vicinity of this fort, and the bombardment began at twilight and, for seventy-two hours, we had a bombardment which did not cease except for a few minutes in the early hours of every morning. The noise was absolutely tremendous. Shells fell all over the place, and there was hardly a part of the ground where a shell had not fallen. You could see – especially at night – the light of the German guns and the light of the shell exploding. The noise was more terrific when a shell, instead of exploding on the ground, exploded in a tree. It made a tremendous roar: you could see clouds of black smoke coming from the explosions and various colours from blue to red to yellow to orange. It looked like fireworks – but not very well-regulated fireworks. Naturally.

My duty was to direct the fire of my battery on the German trenches, twentyfive metres from the one in which I was. Around me, everybody was very nervous.

The shells which came right into the middle of the

French trenches

, and killed many people, did not appease our fear. We were afraid – but we had to do our duty and everybody did it.

I was connected to my battery with a telephone and I gave that battery every order to make the fire as effective as possible. We had a very small observation post in that trench, and one day I found the captain who was doing the work which I was about to do, killed by a bullet in the forehead, looking through the hole of the observation post. No need to say, it's an experience which gave me some fright. The privates and the officers during this battle were absolutely working as one man; everybody was doing what he could. Everybody thought it was necessary to do what they were ordered to do, no matter of how difficult or how terrible it was during that tremendous roar.

When the German fire ceased, the Germans jumped out of their trenches and tried to get into ours. There were terrible fights inside the trenches,

because our soldiers were trying to hold the assault. It was a very sad thing to see all these soldiers, German and French mixed together, sometimes fighting with bayonets.

During the rare moments of rest, the soldiers were not lonesome. They had still a very good spirit, teasing each other, and keeping busy as much as they could, in their private mood. For instance, they were very much interested in the copper belts of guns, which they used to make rings – using small files – for their sweethearts or their wives or their sisters.

When the wind was in our favour, we could smell ether from the German soldiers, which they drank in order to make the assault more effective. On our side we were given brandy to pep us up.

Private, French Army

At the end of April, we were astonished to see that the Germans had put sign boards on their trenches, writing in French that 'You are going to Verdun and good luck to you'. The battle had started in February, and we knew what was going on. We left our trenches and we were taken by train to a place a certain distance from Verdun and we had to walk by night – a very difficult long and hard walk. We arrived at Verdun and remained south of the city in barracks. We were there for a day. We were told not to move and not to show ourselves. When the night came, we went to the front. I had to go into a tunnel on the railway line from Verdun to

Meaux

. In this tunnel lived about a thousand men, who had been there for months. It was filthy, smelly; we had the impression we could cut the air with a knife. From there we went to the Fort of Tavannes. My job was to run from the

Fort of Tavannes

to the

Fort of Vaux

which was about two miles, running from shell-hole to shell-hole. What was most surprising was the landscape. There was not an inch of earth that had not been turned over and over. Some troops were digging trenches, to enable us to get from one place to another. As quick as they could work, the trenches were filled again by bombs and shells.

The Germans attacked heavily every day and every night. We had to live on our reserve foods – biscuits, chocolate, corned beef, but sometimes soup and coffee would arrive, if the men who had gone to fetch them were not killed on the way. The most terrible thing was thirst. As a runner from Tavannes to Vaux, I had to bring water and orders, and come back with the

wounded on my shoulders – or on stretchers if we were lucky enough to have two of us together. What we were eager to know is how long we would stay. We knew that we would be relieved from Verdun when the casualties would become a certain percentage of the troops.