French Literature: A Very Short Introduction (20 page)

Read French Literature: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: John D. Lyons

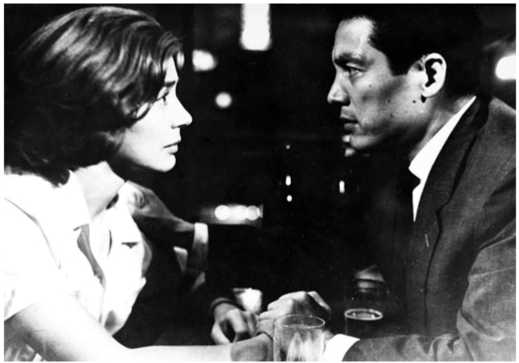

16. A scene from Alain Resnais's film Hiroshima man amour (1959)

Duras's characters are believable, yet opaque. They are what they

say, and what they say is about love and destruction. The force

of the screenplay is in large part the incantatory dialogue, which

slides from apparently realistic conversation to something far

from ordinary speech, like the actress's repeated utterance: `You

kill me. You do me good' (Tu me tues. Tu mefais du bien), one of

the most explicit voicings of an erotic view of war, colonialism,

and the relation of cultures that is ubiquitous in Duras's work, and

appears, indeed, in other novels and screenplays of the late 1950s,

when France was gradually and painfully losing its colonies. At the

end of the filmplay, Duras makes explicit the identification of the

man and the woman with their cities. The French woman looks

at her lover - the stage directions note `They look at each other

without seeing' - and says `You are Hi-ro-shi-ma', to which he

replies, `That is my name. Yes. [That is only as far as we have come

still. And we will stay there forever.] And your name is Nevers.

Ne-vers-in-Fran-ce' (Hi-ro-shi-ma. Nest ton nom.-Nest mon

nom. Oui. [On en est la seulement encore. Et on en restera la pour

toujours.] Ton nom a toi est Nevers. Ne-vers-en-Fran-ce). Duras

here approaches the allegorical use of character most prominent

in the Middle Ages and then glimpsed again in Bonnefoy's poetry.

In the last two decades of the 20th century and the first decade of

the 21st, the grand old men of the Second World War generation

left the stage of French literature to a new cast of writers, with

new concerns. The many novelists among these contemporaries

generally leave behind the formal experimentation of the nouveau

roman. Many of these authors, such as Antonine Maillet (1929),

Maryse Conde (born Beaucolon, 1930), Helene Cixous (1937),

Assia Djebar (Fatima-Zohra Imalayene,1936), Daniel Pennac

(1944), Raphael Confiant (1951), Patrick Chamoiseau (1953),

and Michel Houellebecq (Michel Houellebecq, born 1956, Michel

Thomas, la Reunion), and Calixthe Beyala (1961), were, like their

predecessors Marguerite Yourcenar (1903-87, born Marguerite

Cleenewerck de Crayencour), Albert Camus (1913-60), Saint-John

Perse (1887-1975), and Claude Simon (1913-2005), born outside of

continental France - the French Metropole, or the `Hexagon', as it is

often called. Others were born within the Hexagon: Annie Ernaux

(1940), J. M. G. Le Clezio (1940), Didier Daeninckx (1949),

Marie NDiaye (1967), and Marie Darrieussecq (1969).

Francophone writers, or writers in French?

Most of these authors have in common that they manifest a

paradoxical shrinking and expansion of French literature. The

France of the turn of the 21st century had lost a number of its colonies (Algeria, Indo-China, Morocco) but still sees its cultural

sphere, its `soft power', grow, as the French are among the most

outspoken in claiming to resist the influence of United States

culture. For the last several decades, it has been common to

describe some of these authors - for instance, Maillet, Conde, and

Chamoiseau - as `francophone' writers, while others - such as

Cixous, Houellebecq, and Camus - were never classified as such,

though all of them were born outside European France. Who is,

or what is, a `francophone' writer? And is there a `francophone

literature'? According to the authoritative French dictionary, Le

Tresor de la langue francaise, the term, which dates to 1932, simply

means someone `who speaks French' ([Celui, celle] qui parle le

francais), but in English-speaking universities the term has been

used almost exclusively to designate writers from Africa, the

Caribbean, and North America. It is undeniable that much of the

vitality of today's literature in French comes from the recognition

of such important writers as Leopold Sedar Senghor, Ousmane

Sembene, Cheikh Hamidou Kane, and Birago Diop from Senegal;

Ahmadou Kourouma from the Cote d'Ivoire; Driss Chraibi and

Tahar Ben Jelloun from Morocco; Roger Dorsinville and Rene

Depestre from Haiti; and many others who have in common both

the French language and the experience or cultural memory of

French colonial culture. But questions remain as to the conceptual

framework within which such writers are to be situated.

On 16 March 2007, the Parisian newspaper Le Monde published

a manifesto entitled `For a "world-literature" in French' (Pour

une `litterature-monde' en francais), signed by a group of 44

influential writers. In it, they declare that that year marked the

`End of francophone [literature]. And [the] birth of a worldliterature in French' (Fin de la francophonie. Et naissance d'une

litterature-monde en francais). There are different ways of looking

at how such a distinguished group of `francophone' authors came

to the point of announcing the end of the literature that had

brought them to the attention of a wide public. One could say that

the academic concept of `francophone literature' - conceived by its promoters primarily as a way of creating greater inclusiveness

within the study of literature in French - had been such a great

success that it outgrew its usefulness. One could also say that the

concept of `francophone literature' collapsed under the weight of

its own inconsistencies and incoherence. And, finally, one could

say that the term seemed racist and insulting to many of the

authors to whom it was applied. As Tahar Ben Jelloun (1944),

the Paris-based Moroccan writer, has said:

To be considered francophone is to be an alien, someone who comes

from elsewhere and who is told to stay in an assigned place somewhat

off to the side of `true' French writers [ecrivains frangais de souche].

`La cave de ma memoire, le toit de ma maison sont des mots

francais', in Pour one litterature-monde, ed. Michel Le Bris and

Jean Rouaud (Paris: Gallimard, 2007), P. 117.

And these various explanations are not incompatible.

There will always be reasons to sort literature into a multitude

of categories, including the region in which a text is written; the

period; the gender, class, race, religion, sexuality, or political

affiliation of its author; the formal or generic characteristics of the

text itself; the mode of diffusion or publication; and so forth. At

the turn of the century, a major thematic consensus among writers

in French is that the apparently stable categories of identity for

individuals, nations, and other groups no longer can be taken

for granted, including francophonie - not that boundaries and

belonging are themselves outmoded, but that they have exploded

exponentially and are now the source of endless variations of

authorial and narratorial voices and of protagonists.

A novel from history with a new voice

Let us consider, for example, a very successful historical novel

by a French author from Guadeloupe, Maryse Conde (1930) I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem (Moi, Tituba, sorciere noire de

Salem, 1987), in which the protagonist and narrator is an African

slave brought from Barbados to the colony of New England and

tried as a witch in 1692. Orphaned as an infant and chased off

the plantation to die in the forest, she is raised by an African

woman healer to learn of herbal medicine and of communicating

with the dead. Not a slave, for she was chased away rather than

sold, she looks at life differently from her African compatriots,

but she accepts to become a slave from love. She follows her

husband when he is sold and sent from Barbados to Boston. The

character Tituba is founded on a real person, about whom Conde

gathered all she could from the archives of the witch trials of late

17th-century Massachusetts (Conde has given Tituba African

ancestry, though this is not the prevailing view among historians).

But in trying to give Tituba the biography that was never written -

or rather, the autobiography that she never wrote or that did not

survive - Conde clearly writes for a late-20th-century reader who

will necessarily think in modern terms. Tituba uses the terms

`racism' and `feminism' to describe outlooks and practices, the first

to describe the world as it really was and the second to evoke an

aspiration that Conde supposes women of the time must have felt.

The character-narrator Tituba is a person of the imagination in

more than one sense. She is not simply a version of an historical

figure as Conde imagines her, but Tituba is also a character with

the gift of imagination or vision to look forward to the future, a

kind of Maryse Conde in reverse. As a wise woman, or `sorcerer',

Tituba can see and communicate with the dead but also with

those who are alive after her own death.

Moi, Tituba clearly exceeds any bounds of the `francophone'

novel - it is not surprising, therefore, that Maryse Conde signed

the 2007 manifesto. It is a work in French that does not represent

a French-speaking culture but rather the English-speaking

colonial world of the 17th century. Tituba, an English speaker,

tells her story in French without any apology. The work often

refers to other literary traditions; for instance, Hester, the heroine of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter (1850) makes a

surprising appearance as a friend and perhaps lover of Tituba. The

other characters, good and bad, are British, American colonials,

African slaves or Caribbean-born slaves of African and mixed

European-African descent (like Tituba herself, a child born of her

mother's rape by an English sailor on board the ship Christ the

King), and Portuguese Jews.

A consistent and very explicit aspect of Tituba's values and

personality is her resistance to the appeal of vengeance, even in

the face of repeated and extreme violence, such as the execution

(the murder) of her mother for having resisted a plantation owner

who attempted to rape her. Equally important is her refusal to

accept the split into placative `happy slave' exterior self and cynical

but `free' inner self - a stance adopted by her husband John

Indian. Implicitly, Tituba conveys the view that this claim to inner

`freedom' is itself a deformity that debases the person and prevents

any real happiness.

The metamorphosis of the heroine

`Witch' is a term applied to women usually to insult or to threaten,

but Conde has turned things around by making Tituba a real

heroine, clearly implying approval of Tituba by the reader.

A still more unlikely reframing of roles takes place in Marie

Darieussecq's Pig Tales (1996 - the French title Truismes is a

play on the word `truism' and the word truie, `sow'), where the

narrator-heroine finds herself being transformed into a sow.

Darieussecq (1969) has written something resembling Voltaire's

conte philosophique and Kafka's `Metamorphosis' but with a voice

that is unique in its self-deprecating naivete. While the feminist

premise might seem rather obvious (i.e. that men both view and

treat women like `sows' - one of the infinite number of insulting

terms for women, particularly in terms of their sexuality), making

the conceit unfold is a tour de force. To take the metaphor of the

truie and literalize it into a fantasy set in a very realistic modern world is particularly difficult to do within a first-person narrative.

Unlike Kafka's Gregor Samsa, whose definitive transformation

into a cockroach has already occurred at the start of the story,

Darieussecq's nameless young woman morphs into and out of her

piggish form gradually, and the boundary line of her interactions

with the male characters is also fluctuating and indistinct.