French Literature: A Very Short Introduction (18 page)

Read French Literature: A Very Short Introduction Online

Authors: John D. Lyons

Springtime

Published in the midst of the Second World War, The Stranger

(L'Etranger, 1942) belongs to what the author, Albert Camus

(1913-60), called his `cycle of the absurd' along with his essay The

Myth ofSisyphus (Le Mythe de Sisyphe) and his play Caligula. A

simple glimpse of the titles of the three works shows an emphasis

on central characters who do not fit into positive heroic positions

within their society but are outsiders, failures, monsters - or all

these at once. French literature, at mid-century, was certainly

itself not marginalized. The generation of authors who lived as

adults during the Second World War produced six winners of

the Nobel Prize in Literature (Francois Mauriac, 1952; Albert

Camus, 1957; Saint-John Perse,196O; Jean-Paul Sartre, who

refused the award, 1964; Samuel Beckett, 1969; Claude Simon,

1985). This was a time, clearly, when French writers had captured

the attention of the world. In some ways, they were all either

themselves outsiders (four of them born outside of European

France) or wrote memorably about outsiders (Mauriac in Therese

Desqueyroux,1927; Sartre in La Nausee, 1938).

An unlikely hero

The title of L'Etranger designates its protagonist Meursault, a

young man of modest condition and education, who works in

an office in Algiers, and who, for no particular reason, shoots and kills a young Arab. The story, told in simple language in

the first person singular, shows Meursault gradually growing

in awareness of his distance from the society around him. The

text is not formally a diary, but seems to be written from time to

time, sometimes to note what has just happened and at others

to present what the protagonist plans to do. There is a rather

affectless quality to Meursault, particularly at the outset, though

perhaps it is not so much a lack of emotion per se as a lack of the

conventional dramatization and expression of emotions in their

usual social form. The first sentence offers a good example:

Today, Mama died. Or maybe yesterday. I don't know. I got a

telegram from the nursing home: `Mother deceased. Burial

tomorrow. Respects: That doesn't mean anything. It might have

been yesterday.

(Anjourd'hui, maman est morte. Ou peut-titre bier, je ne sais pas.

J'ai re(u an telegramme de l'asile: Mere decedee. Enterrement

demain. Sentiments distingues.' Cela ne veut rien dire. C'etait

peut-titre hier.)

In the simple declarative sentences, there is much attention to

detail and especially sensation, with little explanation. We see the

world from Meursault's point of view, that of a kind of Candide,

like Celine's Bardamu, without a philosophy to follow or to combat

(Meursault's narrative does make one wonder what Voltaire's conte

would have been like as a first-person narrative). Meursault enjoys

swimming, smoking, sunbathing, and sex with his girlfriend Marie.

At an outing at the beach, Meursault, playing the peacemaker,

takes a revolver from a friend who is threatening to kill an Arab

with whom he has had a run-in, but later Meursault uses the gun

to shoot the Arab. His account gives no place to fear or hostility,

but rather to the heat, the blazing brightness of the sun.

The most remarkable moment of the novel is Meursault's

discovery of himself just before his execution. Throughout the narrative, the protagonist-narrator seems to record what happens

without thinking about it. There is such neutrality and such a lack

of affect in his view of the world that he himself seems sometimes

to be a person who is not there, almost a recording device. But

his imprisonment and trial - he is tried for who he is rather than

for the death of the Arab - make him aware of his difference from

others, and in his revolt he becomes somebody, a self: `Even when

you're in the dock, it is interesting to hear people talking about

yourself' (Mime sur an bane d'accuse, it est toujours interessant

d'entendreparler de soi). He discovers his existence within the

`tender indifference of the world' (la tendre inderence du

monde), and he concludes by hoping that there would be many

spectators when he is guillotined and that they would greet him

with shouts of hatred. A personage almost without characteristics

finally conceives of himself in a heroic dimension.

The drama of just waiting

If Meursault becomes heroic only by affirming his status as

outsider, Samuel Beckett's protagonists clearly occupy the outsider

position from the start. Beckett (a truly bi-national and bi-lingual

author, both Irish and French) differed, however, from Camus in

distancing his characters from the everyday social world. Often,

the unsympathetic central characters and their consciousness

constitute the entire text, like the voice of The Unnameable, a

novel (1953). The most accessible and best-known of Beckett's

works is no doubt his two-act play Waitingfor Godot (1952),

with its tragicomic tramps or clowns, a play that for some critics

typifies the `theatre of the absurd', a term that was applied also to

the plays of Beckett's contemporary Eugene Ionesco (1909-94),

author of The Bald Soprano (La Cantatrice chauve, 1950) and The

Chairs (Les chaises, 1952). Beckett manages the feat of making

riveting drama out of two men waiting, in a bare landscape next

to a tree, for the arrival of a certain `Godot' whom they have never

met. Where does all this happen? Could these two characters

simply be described as inhabiting the author's consciousness?

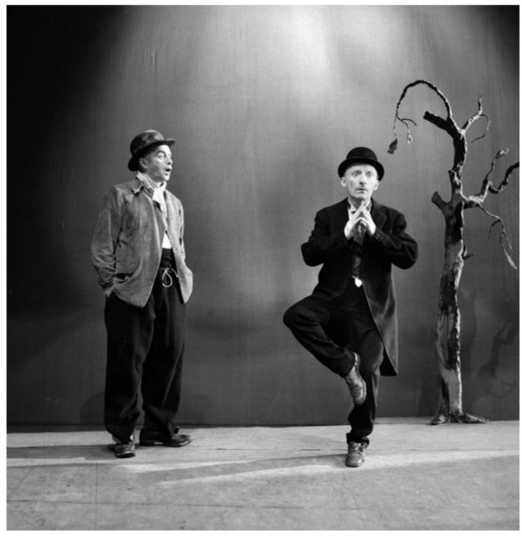

15. Lucien Raimbourg and Pierre Latour in Samuel Beckett's En

attendant Godot, a photograph from the 1956 Paris production by

Roger Blin

The whole work has about it an air of barrenness and desolation

that is accentuated by the simplicity of the language. Beckett

said that he wrote in a foreign tongue to `impoverish' and to

`discipline' himself, so that there would be no style or poetry to the

text. Whether or not this was Beckett's actual reason for writing

in French rather than in English, the argument could be made

that throughout history poetry distinguished itself from ordinary

discourse precisely by the acceptance of linguistic constraints.

For most of the millennium of French literature, lyric poetry has

been written in fixed forms of verse length and rhyme scheme that `disciplined' the writer. In a similar vein, significant works like

the medieval Roman de la Rose stripped away concrete secondary

characteristics from its personae to concentrate both on what is

most central to their story and what is most universal. Although

the actors of Waitingfor Godot cannot easily be interpreted as

allegorical abstractions - into terms like `hope', `despair', `reason',

and so forth - their dialogue conveys a darkly comical version of

human existence reduced to its most schematic.