Gallipoli (80 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

And what an impression they make!

âThese troops,' Bean records, âcame to the tired and somewhat haggard garrison of Anzac like a fresh breeze from the Australian bush.'

âGreat big cheery fellows, whom it did your heart good to see,' wrote another Australian. âQuite the biggest lot I have ever seen.'

Huge, healthy men of robust good spirits, strong of limb, clear of eye â just what the doctor ordered.

Careful, though â¦

Though it is tempting to throw such men straight onto the frontline to relieve the exhausted troops there now, or to launch them immediately into a battle planned for Hill 60, which is about to be launched, General Birdwood is careful not to do so. Instead, after bivouacking them for a short time at the foot of the Sphinx, he sends them up to Bauchop's Hill, where they can act as reserve to General Godley.

It would be madness to throw such fresh troops straight into a major battle, and even General Godley will not countenance it â¦

20 AUGUST 1915, NOT A RED LETTER DAY

Ever and always, it is the shining spot in the otherwise very dark lives of the Turkish soldiers at Gallipoli. In the midst of all the death and destruction, the fear and ferocious fighting, just occasionally a messenger arrives from their own villages â âThe messenger arrived! The messenger arrived!'

93

â bringing letters, food, gifts and news from home.

The soldiers crowd around the messenger. âWhat of my family?'

My fiancée?

My children?

My parents?

And, of course, the messenger â usually an old man from home â does his best. But then the hardest part â¦

âWhere is the son of DurmuÅ Kara Ali?' the messenger asks,

94

as he has a gift of a handkerchief for him, from his girl in the village.

âBlown to pieces by a bomb three days ago â¦'

95

The messenger drifts off as, devastated, he tries to fathom how he is going to be able to break that news to the girl. The soldiers' eyes fill with tears.

There is similar angst in the Anzac lines. âI've seen anxious troopers, with yearning eyes,' one soldier would record, âhang round till the last letter and postcard were sorted â then wander away silently, and gaze dry-eyed over the blue Mediterranean. [All of them] would have given the world to be able to take a peep at the wife who scanned the casualty lists so eagerly as they appeared in the papers, and the kiddies who strutted round proudly, saying, “Daddy's gone to the war”.'

96

21 AUGUST 1915, MELBOURNE, A TELEGRAM ARRIVES

For those men and boys who don't go to war, this has to be the biggest bastard of a job left: delivering cables. Oh yes, it had been cushy enough early on, as it had mostly been standard fare of safe arrivals, babies born, engagements announced and the blessed news that âI'll be home soon'. But ever since this business at the Dardanelles had descended into carnage, the telegraph boys have a new kind of cable to deliver. They are from the government, and always stamped

Personal Acknowledgment of Delivery

, meaning that it is the job of the boy to get the signature of the person to whom it is addressed. Pretty soon, everyone knows that URGENT TELEGRAM at the top is almost always a death sentence, because the news is invariably that a distant Australian soldier is either MISSING IN ACTION, seriously wounded or KILLED IN ACTION.

Sometimes it is all you can do to get the signature out of them, and the scenes you are in the middle of are terrible. And so it is on this day, for Myrtle White â¦

Dear Madam,

It is my painful duty to have to inform you the sad news of the death of your husband, Lieutenant Colonel A. H. White, Commanding Officer, 8th Light Horse Regiment ⦠which occurred in action at Gallipoli on the 7th August 1915.

I am instructed to convey to you the sincere regret of the Minister for Defence and the Commonwealth Government in the great loss you and the Army have sustained by the death of the gallant officer.

Yours faithfully

Capt.

Officer i/c Base Records

97

Myrtle's grief is deeper than the ocean. To think of her beloved husband now dead in a ditch on the other side of the world is almost more than she can bear, but bear it she must, for the sake of their infant son, to begin with. In the tragic tradition of war widows through the ages, it is now she who must soldier on ⦠alone.

In at least one instance on the Gallipoli Peninsula, at around this point in the campaign, a family member decides to do more than just grieve from afar. For the story will long be told how a Brigade Commander notices something strange about one of his soldiers in the trenches and takes a second look.

âHow old are you?' he asks the soldier softly. âTake off your cap.'

âForty, sir.'

âNo. Your real age.'

98

There is a pause. A grimace. And then a confession.

âSixty, sir!' the old man replies.

After both of his sons had been killed on the day of the landing, he had lied about his age, joined up and come looking for any trace of them â¦

THE BATTLE OF HILL 60

For connoisseurs of military futility, valour, incompetence and determination, the attacks on Hill 60 are in a class of their own.

1

Robert Rhodes James

The Angel of Death is abroad throughout the land ⦠You can almost hear the beating of his wings!

2

John Bright, British Member of Parliament (1843â1889) and orator

23 AUGUST 1915, SLAUGHTER ON HILL 60

Shattered, missing limbs, their faces contorted into the grimaces of agony they wore when death overtook them ⦠Hundreds of dead men, many disembowelled, now lie all over the lower reaches of Hill 60, clogging up the trenches, staring glassy-eyed at the weeping sun.

It had been a saga of devastation â¦

To begin with, Hill 60 is really just a scrubby lump of land rather than a hill, its tired summit just 60 feet above sea level. Charles Bean calls it âlittle more than a swelling in the plain',

3

and it lies just a mile back from the beach that stretches between Suvla Bay and Anzac Cove.

Despite its diminutive stature, the capture of Hill 60 (along with Scimitar Hill and W Hills immediately to its north) will allow the Allied AnzacâSuvla line to push eastward into the Anafarta Range and, crucially, shorten that line. Turkish rifles currently outnumber the Allies' 75,000 to 50,000, so rounding off and contracting the Allied line is an important defensive strategy that will help secure the âbridge' between the two bridgeheads â Suvla and Anzac â while limiting any immediate threat to the Allies' Suvla occupation. The problem remains, however, that the Turks hold the high ground and will fight to the death to keep it against those who would try to seize it from them.

Who can the Allies call on in their hour of desperate need?

Why, none other than the famous 29th Division. No matter that the 29th have been shot and shattered from ship to shore and back again so many times since their tragic landing from

River Clyde

. No matter that most of the fine soldiers who stood before King George in March stand no more, as no fewer than 30,000 men have now gone through their doomed ranks since the beginning of the campaign, only to be spat out the other side, either dead or wounded. No matter, even, that they can muster fewer than 7500 soldiers capable of holding a rifle. For their arrival on this battlefield, poised as they are to take Scimitar Hill on the left, lifts the army as one.

A couple of days earlier, on the afternoon of 21 August, 500 men of the AIF's 13th and 14th Battalions had been in the thick of the attack on Hill 60 ⦠only to be decimated by machine-gun and artillery fire. The shelling had started another fire in the brush, and all those lying prone from wounds were incinerated. And yet more troops had gone to the heavily held position â including the 750 untried Dinkums of the 18th Battalion who have not been ashore a day.

Hence the dead â¦

Yes, General Godley really had intended to keep those huge-limbed, fresh and cheery-faced Australians in reserve, but then things had gone wrong, you see, with so many of the experienced troops killed that he simply had had to throw them in and hope for the best.

And then the next night, in desperation, Brigade-Major Guy Powles of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles had summoned the Commanding Officer of the 18th Battalion and advised his new colleague by the light of a candle, âYou are to assault with bomb and bayonet only.'

âBut,' the Commander had interrupted, âwe have no bombs â¦?'

âYou must do the best that is possible without them.'

4

And so they had. But in the maelstrom the brave soldiers of the 18th â most of them from the Sydney inner-city suburbs of Annandale, Leichhardt and Marrickville â had simply been cut to pieces. Hamilton's report to the War Office after the initial battles of 21 and 22 August gives some clue as to how grim the situation is now:

The troops attacked with great dash and stormed the lower slopes of the hill in spite of strong entrenchments, but I regret to say they were not able to attain their objective nor even to consolidate the position gained ⦠Casualties not yet to hand, but I fear they amounted to some 6,000 in all â¦

5

When even Hamilton concedes that victory may not necessarily be just up the next hill, how bad must things be?

Very bad. The 29th Division has briefly held the crest of Scimitar Hill before being repelled with severe casualties, and the 11th Division has been unable to maintain a contiguous line in the first Turkish trenches on W Hills.

And yet Hamilton and Godley remain as intent as ever on securing Hill 60, come hell or high water. With the spirit most fervently displayed by General Hunter-Weston in months gone by, Godley continues to feed in whatever troops he can garner. They

must

have Hill 60.

25 AUGUST 1915, CAIRO, THE WORD COMES THROUGH AND THE WORD IS GOOD

He has the cable!

General Hamilton has graciously acceded to Keith Murdoch's request from Cairo to visit Anzac Cove. And yes, first he must sign the War Correspondents' Declaration, but that is a mere formality. He puts his elegant signature on the standard form without a second thought:

I, the undersigned, do hereby solemnly undertake to follow in every particular the rules issued by the Commander-in-Chief through the Chief Field Censor ⦠[not to] impart to anyone military information of a confidential nature ⦠unless first submitted to the Chief Field Censor.

6

K. Murdoch

27 AUGUST 1915, THE WORD COMES THROUGH AND THE WORD IS BAD

After three weeks in the field without rest, at last the word comes through. The shattered survivors of Colonel Brazier's 10th Regiment of the Australian Light Horse â now only mustering 160 men from their original contingent of 500 â are to be relieved from defending Russell's Top. They do not have to be asked twice. Just after sunset on this coolish evening, they are relieved by some more of the Dinkums and set off with the slightest of skips in their otherwise delirious step. Once the Light Horsemen get close to the âsafety' of Table Top, where they are meant to rest, bullets are buzzing around like flies on a turd. They decide to push on.

Worse, at 9 pm the word comes back: âSling off your pack, and come forward with just your fighting gear and ammunition.'

7

The men look at each other, slack-jawed with disbelief, but do as asked. Within minutes, they receive a countermand: head towards Suvla Bay, to the south-western ramparts of Hill 60.

Again they follow orders, just as they follow directions, and soon come closer to Hill 60, all the time passing ever more wounded men coming back from the firing line â including soldiers of Monash's embattled 4th Brigade, who are another group on the lengthy list of troops who can't seem to gain a moment's relief.

âIt can be easily understood,' Thomas Kidd would write in his diary, âthat we were not in very good fettle, although the men were all game enough for anything and had no time for grumblers.'

8

Led by Brazier, the 10th Light Horse keep moving. Because the whole area has been dug out with sapping trenches, they are able to get within half a mile of Hill 60 without ever being seriously exposed to enemy fire. Then it becomes very tricky indeed. With a wretched squeal, one of the few mules they have goes down, but, mercifully, the rest get through to the trenches at the back of the hill. At 11.30 pm, the hardy South Australians of the 9th Light Horse show the 10th Light Horse how best to position themselves and give them fair warning that, come sun-up, there will likely be more shrapnel than they have ever seen before.

By the flickering light of exploding shells, the 10th Light Horse Regiment can now see just what they are truly facing. One man squints through the periscope to focus: the hill before them is covered in a fresh crop of corpses. The ones on top are the men of Monash's brigade, who have fallen just this afternoon. Lying underneath them are Indian, British and Gurkha soldiers, together with more from the New Zealand Mounted Rifle Brigade and the AIF's 5th Brigade, a terrifying testimony to all those who have tried to take the hill.

The 9th and 10th Light Horse Regiment, it seems, are the last two units that Godley has to throw into the fray.

Meantime atop Hill 60, such as it is, Colonel Halil and his 1350 Turkish soldiers remain under severe pressure. The enemy has captured trenches at the bottom of the hill's slopes and are now within 300 yards of the summit. What is also clear is that Colonel Mustafa Kemal wants those trenches cleared at any cost. In his breast pocket, Halil has the last message from him:

I am waiting for the following news from you: âThe enemy who entered our trenches have been destroyed, our soldiers have taken the enemy's trenches.'

Any other information you send me is unimportant.

9

And so the 160 men of the 10th Light Horse settle down in the bitterly cold night, waiting for the warmth of the rising sun, while being entirely unsure whether for some of them â perhaps many of them? â it will be the last sunrise they will ever see.

Even as they are settling in, the fighting goes on, and just next to them, twice the men of the 9th Light Horse make charges, using 50 men in each wave. In their last charge, they are wiped out to a man.

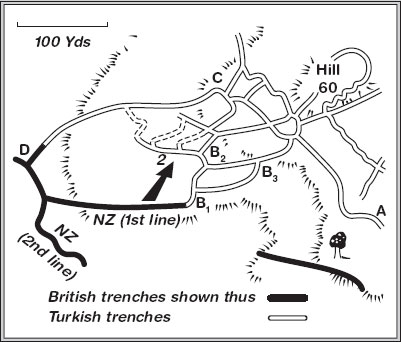

Allied and Turkish trench dispositions, Hill 60, 26 August 1915, after a map by C. E. W. Bean

28 AUGUST 1915, HILL 60, IN GODLEY WE TRUST

Sure enough, the following morning the shrapnel comes thick and fast, with one shell dropping right in the middle of the 10th Light Horse Regiment, but it miraculously fails to explode. Colonel Noel Brazier is not so lucky. Just after dawn, he is hit by a lead ball to his left eye, blinding him instantly. Though it looks like he will survive, he must be led away. Either way, his war is over. However, there is an upside, as he will later write: âGot shrapnel bullet in left eye and good bye to Antill and two wars.'

10

All the 10th Light Horse Regiment can do in the absence of an organised charge is dig themselves into their trenches more deeply, and this they do with some enthusiasm. At 3 pm that afternoon, however, word comes that General Godley has arrived and would like to see the 10th Light Horse Regiment's senior officers â a tad problematic as there are very few left.

In the end, the man who has taken over from Brazier, Major Jack Scott, an accountant from Katanning, Western Australia, summons Lieutenant Hugo Throssell, as well as a 33-year-old grazier by the name of Captain Phil Fry and 20-year-old Duntroon graduate Captain Horace Robertson, to join him in reporting to the General. Quickly, and staying low, they make their way to Godley's position, a safe distance back from the frontlines.

After they arrive, the General is not long in getting to the point: âA most difficult and important piece of work has to be done and you have been selected for it. You must take and hold a trench, the possession of which is absolutely essential to a big operation. Once you have it, you must hold on to it like grim death. The trench is about 80 or 90 yards away from where we now stand, and the ground between is flat and clear.'

11

Somehow, General Godley makes such light of it that, in spite of the yawning gap between their positions on the military hierarchy, Lieutenant Throssell just can't resist.