Georgian London: Into the Streets (39 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

The corpse had no legal status in England; it could not be stolen. But a fresh human corpse had a significant material value to the medical profession. This peak condition was a matter of a few days in winter and much less in the warmer months. In 1752, the medieval stigma that dissection was a form of punishment was reinforced when the statutory law came into place decreeing that all murderers would be subject to dissection, with the words ‘

it is thereby become necessary

that some further terror and peculiar infamy be added to the punishment of death’.

Intimate knowledge of the human body, its possible variations from patient to patient, and the courage to act swiftly with a steady hand did not come easily. Natural revulsion at cutting into human flesh was compounded by popular sentiments about the sanctity of the body, particularly in death. Yet the would-be surgeon had to overcome this. In 1811, Fanny Burney recounted in a letter the story of her mastectomy following a diagnosis of breast cancer:

I began a scream that lasted unintermittingly during the whole time of the incision … when again I felt the instrument - describing a

curve - cutting against the grain … then felt the Knife tackling against the breast bone - scraping it!

The entire operation was done, including dressing, in twenty minutes and with no form of anaesthetic. It was understandable that surgeons were regarded, in Burney’s words, as ‘practically insensible’ to the sufferings of their patients. They had to be. This insensibility was cultivated in the very early stages of their education by the handling of fresh corpses, and perhaps contributed to the moral ambivalence which surrounded the procurement of the necessary bodies. There is no doubt that the surgeons running these schools were treading a fine line.

Although bodysnatching was common in London as soon as, if not before, the private anatomy schools were established, the only available documentation dates from the 1790s onwards, when the practice of surgery and the number of medical students grew dramatically.

In 1793, there were 200

medical students in London; by 1823, there were over 1,000. In theory, they were all competing for access to the 100 corpses legally available. Even by the early eighteenth century, anatomists had separated themselves from the act of obtaining corpses. Instead, they employed their medical students, or ‘agents’ – men and women who went into prisons and hospitals to persuade those approaching the end of their lives to turn over their corpse in exchange for a financial incentive. Other agents were the bodysnatchers, known as the Resurrection Men.

The Borough Gang of resurrectionists operated from the beginning of the nineteenth century until 1825. They were led by Ben Crouch, a former porter at Guy’s Hospital. Sir Astley Cooper, the Professor of Anatomy at Guy’s, employed Crouch and his gang to source bodies for the students. Cooper was so dependent upon the gang’s efficient and constant service that when a member ended up in prison, usually for unrelated petty crime, Cooper continued to make payments to their family.

The Borough Gang were particularly good at what they did. They hung around graveyards and funeral processions to identify their targets. The night after burial, they dug down to one end of the coffin and smashed their way in, then hauled the body out. The dirt was

then replaced and the grave put back as it was found. Londoners were increasingly aware that the graves of their friends and family might not be safe, and they placed markers in the fresh earth so that they could check for disturbance. Some even rigged booby traps. Still, the Borough Gang were successful. They didn’t always wait to dig bodies up either, but broke into houses where the body was being prepared for burial.

The resurrection trade became increasingly sophisticated, with complicated pricing structures. Freakish or unusual bodies commanded high prices.

Children under three feet

in height were classed as ‘large small’, ‘small’ or ‘foetus’ and priced by the inch. There was a separate trade in teeth, which were sold to dentists to furnish dentures. Some may even have attempted to transplant the dead teeth into living mouths. In 1817, Ben Crouch left the Borough Gang to follow the British Army in France and Spain where he raided the bodies of the dead for teeth, making a prosperous living.

The public horror of the resurrectionists and dissection was growing as rapidly as the trade itself. Joseph Naples worked with the Borough Gang in 1811 and kept a diary of the gang’s extensive work throughout London, often taking five bodies a night from assorted cemeteries, and sometimes many more small corpses. On Tuesday 10 December, he wrote: ‘Intoxsicated all day: at night went out & got 5 Bunhill Row. Jack all most buried.’ The diary also

shows how profitable bodysnatching was: on the 9th and 10th of the following January, Naples took in over £20 from St Thomas’s – and that was only his share of the profits. An average annual wage for a labourer was only around £40 at that point. Naples was caught, after being turned in by Ben Crouch, and was sentenced to two years in prison. He escaped, Sir Astley Cooper having intervened on his behalf.

At around the same time, many surgeons in London formed a loose club which served two purposes. The first was to share information on both bodies and pricing, and to prevent the snatchers charging outrageous prices. The second was to raise awareness of the need for bodies. In 1828, the Burke and Hare murders in Edinburgh, committed to supply corpses for dissection, shocked Britain. A Select Committee was appointed to look into the need for a better system. Before the committee, Sir Astley Cooper described his loyal gang as ‘the lowest dregs of degradation’. This led to the passing of the 1832 Anatomy Act which allowed the corpses of paupers, and people who had died ‘friendless’, to be anatomized. The rising popularity of surgical procedures, as well as the Act, lessened the stigma about dissection, although bodysnatching remained one of London’s marginal trades right into the twentieth century.

Southwark was home to some of London’s major industries. All along the river were the ‘

great timber-yards … One would fear that the forest of Norway and the Baltic would be exhausted, to supply the want of our overgrown capital.’ There were also steelyards and ‘the vast distilleries … There are seldom less than two thousand hogs constantly grunting at this place; which are kept entirely on the grains

.’

Windmills throughout Southwark and Lambeth milled flour for much of London. In the early 1780s, Samuel Wyatt decided to employ new technology in the creation of a large flour mill. In March 1783, he negotiated the lease on land now covered by the railway into

Waterloo. He began to build quickly and, in 1786, the first engine was installed. It was the first of three steam engines designed by Boulton & Watt, and was one of the earliest to be used for such industrial purposes. The mills were opened in a flush of publicity, attended by prominent Londoners, including Josiah Wedgwood.

Arson was suspected. The local mill owners had watched Albion Mills turning out far more flour in a day than they could hope to produce in a week. Steam power had divorced Albion Mills from the vagaries of the weather, and many suspected that the owners were speculating by stockpiling flour. William Blake, born in Lambeth, had seen the significance of Albion Mills: even the name conjured some idealized version of the nation. But for Blake, these were the ‘dark, satanic mills’ of Jerusalem.

The Albion Mills were never rebuilt. On the night of the fire, many of the poorer inhabitants of Southwark danced in the street for joy at the demise of the industrial monster. It was a symbol of the industrial revolution, heralding the arrival of a new, mechanized age – an age that could not be held back for long.

The south bank was already a centre for brewing, wire-making, glass-making and anchor-smithing. Then, in 1769, Widow Coade arrived in Lambeth from Lyme Regis, bringing with her one of Georgian London’s forgotten wonders: Coade stone or, as she called it,

Lithodipyra

.

Eleanor Coade was born, in 1733, to a family of ceramicists, and to a father who couldn’t stay solvent. He died in 1769, and in the same year she and her daughter, also Eleanor, arrived in Narrow Wall, Lambeth, taking over an artificial stone foundry from one David Picot, who retired or left the business two years later.

There had been a history of artificial stone being made in the area, but the Coades had a secret. Their stone was finer and more durable

than anyone else’s and could be cast into very fine relief. They made it to a secret formula, which they guarded during their lifetimes. The younger Eleanor Coade was a formidable artist and businesswoman, and she took on the title ‘Mrs’, although she never married. After her mother’s death, in 1796, she took the business to a new level, and the improvements in the ‘mix’ are probably down to her.

Coade soon became the stone to have, due to the imaginative and lively modelling. In addition, it stays clean and isn’t eroded by pollution. Sculptors were drawn not only from Britain but also included some of the talented foreigners working in London at the time, such as John de Vaere who later worked for Wedgwood. Customers could commission what they wanted, or choose from the Coade’s catalogue. They could also visit the premises, where huge garden statuary and architectural ornaments were displayed everywhere. In 1799, Eleanor Junior appointed her cousin and chief modeller, John Sealy, as her partner. In the same year, they opened Coade’s Gallery on the Pedlar’s Acre at the south end of Westminster Bridge.

There was almost no style, or size, in which Coade’s were not willing to work. Their designs range from Indian animal friezes to gates to Greek Revival statues. They had a team of in-house designers but also worked to designs by Joshua Reynolds, Benjamin West and James Wyatt. The stone was used throughout London, and was also shipped to South Africa, Ceylon, Gibraltar and the West Indies. A Gothic font was created for a church in Bombay. A bank in Montreal ordered much of its decoration from the Lambeth firm. The King of Portugal ordered a special set of architectural works for his complex in Rio de Janeiro (some of which now form the gates to Rio’s zoo).

Eleanor Coade died in her house in Camberwell Grove, in 1821. She was a devout Baptist. The recipe for the stone still exists, and Coade stone can be made today. The special ingredient which made the mix so workable was not cement, but ceramic. Amongst London’s extant Coade is the shopfront of Twining’s at 216 Strand, and Captain Bligh’s tomb in St Mary’s Churchyard, Lambeth. On the south-east side of Westminster Bridge stands a large Coade stone lion on a pedestal, close to the site of his creation. Originally he had stood outside the Red Lion Brewery, close to County Hall, but was moved to Waterloo

Station in 1949. He was brought to the current spot in 1966, and gazes towards the Houses of Parliament with a somewhat defiant expression. Little wonder, as his testicles were removed in case they caused offence to public decency.

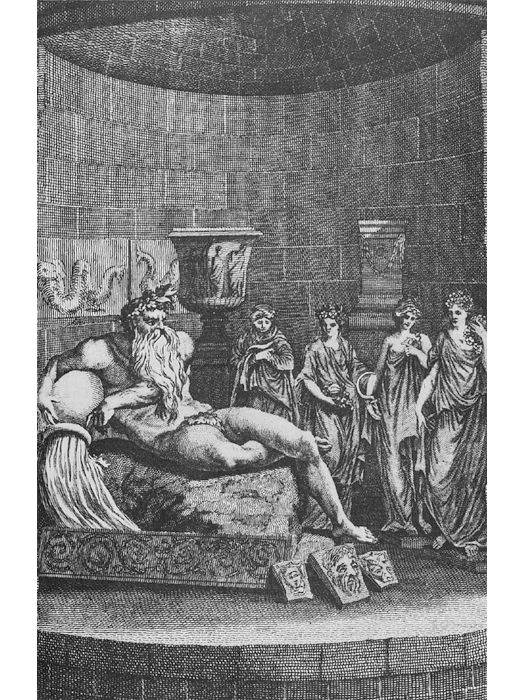

Eleanor Coade’s stone factory, Lambeth, 1784. The interior of the kiln shows the firing of the statues of the Thames river god and the Four Seasons

From the industries of the south bank, large and small, we next turn back to north London proper, and the industries of the East End, which were born, flourished and died all within the eighteenth century.