Georgian London: Into the Streets (40 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

10. Spitalfields, Whitechapel and Stepney

Daniel Defoe, born in 1660, recalled the Spitalfields of his youth: ‘

The Lanes were deep

, dirty, and unfrequented; that Part now called Spitalfields-market was a Field of Grass, with Cows feeding on it, since the Year 1670.’ This pastoral scene did not last long. By 1700, Spitalfields, and Whitechapel to the east, was a mass of open spaces given over to brewing, cloth workers’ animals, and illegal housing. The area had held religious houses and early theatres, including Richard Burbage’s predecessor to The Globe. These open spaces were used for recreation and the relatively low-level commerce of London’s woollen industry. It was also a refuge for many dissenting religions, including the Huguenots and the Jews; immigration has been a constant theme, as well as a bone of contention, throughout the area.

London had been the centre of Britain’s cloth trade for centuries; throughout the city there were areas which concentrated on buying, storing, weaving, dyeing and treating. Even during the late medieval period, the City’s weavers and textile businesses were moving east to make the most of the ample water supply and the open ground. Open ground was very important to the cloth industry: when large bolts of fabric were treated, they needed to be dried on the ‘tenter grounds’ marked on many of the maps of the area. To prevent the dyes settling unevenly, they were pulled out tightly with tenterhooks, giving us the saying ‘being on tenterhooks’.

The ample natural springs and lack of confinement were attractive to other light industries, such as brewing. In 1694, Joseph Truman established the Black Eagle Brewery in Brick Lane, and the ‘brew-house’ came to dominate the area as one of the greatest single employers in Georgian London. The firm soon took up six acres on the east side of Brick Lane.

Their output

was tremendous. (The Truman Brewery building, although a later version, still exists today, now converted into trendy studios for media businesses.)

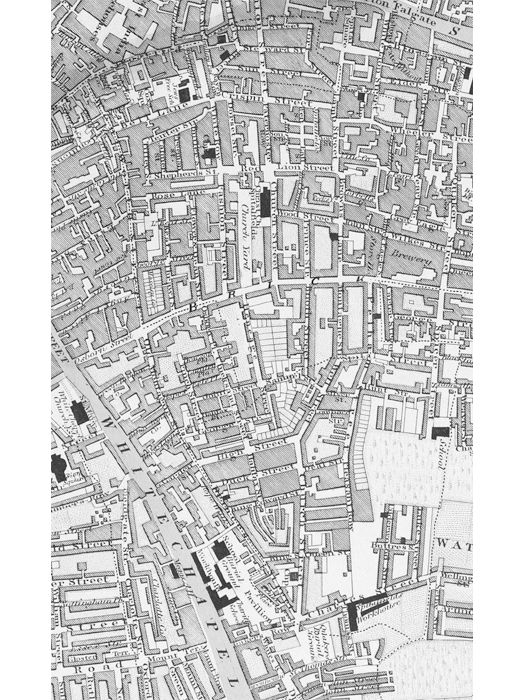

Spitalfields (top) and Whitechapel, detail of map by John Greenwood, 1827

But the area was, and would remain for two centuries, dominated by weaving and cloth-finishing. Wool, long the English staple, was being supplanted in popular taste by linen and, soon after the beginning of the Georgian period, silk. Wool was grown in the provinces, linen usually originated from Ireland, and silk was an exotic product which was imported ready-made. An early attempt at keeping silkworms in England had failed, when James I planted many thousands of trees inedible to silkworms near Hampton Court Palace. From then on, it was deemed easier to obtain silk as a finished product. It was not until the arrival of the Huguenots en masse, in 1685–6, that the weaving community began to dominate the area. Huguenots had brought new techniques, designs and organization with them from France. So devastating was the effect of the Huguenot silk weavers leaving France that, within a few years of their departure, the country went from being a bulk exporter of silks to a bulk importer.

Spitalfields is famous now for the weavers’ houses in and surrounding Spital Square, Fournier Street and Elder Street, which were built in the early eighteenth century and survived both the demolition and ‘improvements’ of the subsequent decades. The area is now associated with London’s artistic community. But as late as the 1970s, it was still relatively run-down, despite being right on the edge of the City. Now, the weavers’ houses are some of the most sought after in London, yet they are not all they seem. Many of them appear large and imposing from the outside, with their basements, three or four upper storeys and light, airy roof garrets, but inside they are only one or one and a half rooms deep, and sometimes these are very small. Elder Street, with its varied architecture, is a fine example of this. The houses were built quickly, on small old plots, and sometimes the rooms did not come up quite square. So the internal fittings, where they survive, contain the odd trompe l’oeil here and there to fool you into thinking they are symmetrical. The weavers of Spitalfields, even at the peak of their success during the first half of the eighteenth century, did not live in such grand style as might at first be imagined; in their housing, as in their fashion, they put on a fine show. The rapid rise and fall of the English silk trade created these streets and

then left them, almost as if frozen in time, waiting for another group of artists to move in.

The arrival of the Huguenots revolutionized the English silk business. As they had come to dominate Soho, so they also came to dominate the Spitalfields and Shoreditch areas of London throughout the eighteenth century.

Suzanne de Champagné

sailed for England, in April 1687, with her siblings. Desperate to escape France, Suzanne’s mother, Marie de Champagné, and her children set out for La Rochelle. Marie was heavily pregnant, and unable to make the sea voyage straight away, but nineteen-year-old Suzanne made a plan to get the children to safety. She negotiated with an English sea captain, Thomas Robinson, to get them to England. At two o’clock that night, she took her smallest sister into her arms, and four sailors carried the whole family on to the boat on their shoulders. They were stowed inside a secret compartment, on piles of salt.

After we were put there and seated on the salt … the trap door was closed again and tarred like the rest of the vessel, so that no one could see anything there … we took care to hold our heads directly under the beams so that when the inspectors, as was their lovely custom, thrust their swords through, they would not pierce our skulls.

The family were let out of the small hold, where the salt was stored with ballast, after the ship had been successfully inspected by the French authorities. Suzanne said that by the time of their release, they had been ‘suffocating in that hole and thought we were going to give up the ghost there, as well as everything we had in our bodies, which was coming out of them every which way’.

They made it to England, but not without some difficulty, as Captain Robinson decided that he wanted more money and would not take them to their chosen destination of Topsham. Suzanne said this was ‘unjust and complained to the governor of the town’, who told Robinson to fulfil his contract. Robinson, of course, dumped

them as soon as he could – in Salcombe, where they were found by local children.

In the end, the Champagné family were successful in their various escapes and were reunited. Suzanne’s experience is by no means unique amongst the Huguenot community; many of the most extraordinary escapes went unrecorded, apart from family legend. Once they had reached London, many of these people, whether noble or not, turned up at the French Church on Threadneedle Street.

The church offered a familiar form of worship. It seems that the Huguenot church was largely an informal one – not dissimilar, for the most part, to a Quaker meeting house. In a sixteenth-century picture of the temple in Lyons, there is even a dog sitting in the aisle, apparently listening to the sermon.

The ‘court’ of the French Church of Threadneedle Street, where members were summoned if they had committed a crime such as adultery, also recorded petty infractions – for example, leaving the church early during the service. ‘

This scandalizes

the English, who hold pastoral blessing in high esteem, whereas we should neglect nothing that may persuade them we are Protestants truly Reformed according to the word of the Gospel.’ English people, such as Samuel Pepys, attended services at the Huguenot churches (Pepys particularly enjoyed the singing).

Not all Huguenots were the serious, God-fearing people Hogarth depicted in ‘Noon’. The court had to reprimand those ‘

members of the congregation spending their days and nights in taverns to abandon their excesses, debaucheries and licentiousness’. The court warned them this was ‘ill befitting their condition as persecuted Protestants and refugees

’. Whatever their expertise in beer, the Huguenots assisted the Trumans with brewing England’s first hop beers, belying the sober reputation the French Church wanted for them.

The Threadneedle Street Church was not only a meeting place and a source of charity, it was also the hub of a knowledge network. Many of these people, particularly those dealing in luxury goods, found Soho to be the most congenial place to settle. Soho, however, would not do for the weavers or those associated with the

silk industry, who needed abundant water supplies and large open spaces.

Weaving in England had been conducted largely as a cottage industry, or by piecework, and was therefore one of the industries most susceptible to changes in the market. Robert Campbell’s words of advice to those thinking of the weaving industry for their children are edged with warning: ‘

They are employed Younger

, but more for the advantage of the Master, than anything they can learn in their Trade in such Infant Years.’ So, the weaving industry tended to make the masters – those at the top – wealthy, particularly if they had a good eye for silk design and fashion. Those at the bottom, who cleaned and fixed machinery or ‘ran’ for rooms full of weavers, remained poor and were liable to be laid off at any given moment, as soon as there was a lull in demand.

Still, there was far more demand for unskilled workers in the silk factories being built in east London than there was in the small, tightly knit households of Huguenot tradesmen establishing themselves in Soho. The poorest of the refugees arriving at the Threadneedle Street Church were sent to Spitalfields to labour for the weavers, and to take sustenance from ‘La Soupe’, the Huguenot charity kitchen.

Many English perceived all the Huguenots who arrived as penniless, and this suited the rich Threadneedle Street Church very well: it could administer charity from within, and strengthen the community. But, in fact, many Huguenots arrived with plenty of money. In 1691, the French Church scolded the parishioners for their large and noisily extravagant weddings ‘

undermining

[the English people’s] compassion for our poor refugee brethren. We should weep with those who weep, not undermine their cause by flaunting wealth and so discouraging charity.’ So, within the Huguenot community itself, there was already a division between those who had arrived with means, and the ‘poor refugee brethren’. The richer members soon established their own church, separate from Threadneedle Street, but allied to it.

At 19 Princelet Street lived the Ogiers. Peter was a silk weaver from Poitou, and his daughter, Louisa, married Soho silversmith Samuel Courtauld. After Samuel died, Louisa continued the business

on her own. In their Cornhill shop she employed women such as Judith Touzeau, a Huguenot girl whose signature appears on receipts from the shop. In the interconnected fashion typical of the Huguenots, Samuel and Louisa’s son, George, was apprenticed in the silk trade, and Courtauld textiles was born, soon employing many French hands.

The structure of employment and social life was very different in the East End to that of the West End, where silversmith Paul de Lamerie was his master’s servant and social inferior only so long as he was an apprentice. The situation for female members of the family and workforce was also different in these larger East End establishments. In the small messuages of Clerkenwell and Soho, a cohesive family structure enabled widows to control the business after the death of a master. They had known many of the apprentices and journeymen for years, most of whom would be happy to pull together to perpetuate a successful enterprise. However, in the larger business model of the East End – where employee numbers were higher, and trade was often business to business – women struggled to continue after their husband died. Daniel Defoe commented on the situation for a widow in such a business, particularly if she had not taken the time to become well acquainted with her husband’s dealings:

…

if her husband

had e’er a servant, or apprentice, who was … acquainted with the customers, and with the books, then she is forced to be beholden to him to settle the accounts for her, and endeavour to get in the debts … and, it may be at last, with all her pride, lets the boy creep to bed to her.

By the time Christ Church, Spitalfields, was finished, in 1729, there was already a growing problem with indigent poor in the area. The Huguenots had, largely, got themselves together and were starting to make huge progress with the creation and sale of fashionable new silks. These were not only used for clothing, but also in furnishings and wall coverings. There was almost nothing fashionable that silk could not be applied to. Yet it could not be grown here. Every attempt to establish native British silkworms had failed. So the nature of the

supply of raw material – coming in from wherever it could be obtained from overseas – plus the fickle nature of fashion itself meant that not everyone was employed all the time, and those who were out of work were finding things increasingly difficult. Violence was not uncommon, as was extreme poverty through lack of work. In 1729, the same year that Hawksmoor’s glorious church was finished, the Spitalfields Soup Society was established to cater for those who had no other means of feeding themselves or their families.