Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World (22 page)

Read Gilded Lives, Fatal Voyage: The Titanic's First-Class Passengers and Their World Online

Authors: Hugh Brewster

Tags: #Ocean Travel, #Shipwreck Victims, #Cruises, #20th Century, #Upper Class - United States, #United States, #Shipwrecks - North Atlantic Ocean, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Travel, #Titanic (Steamship), #History

While recovering from the difficult birth of her second daughter, Elinor began penning a comic novel entitled

The Visits of Elizabeth

, which satirized some of the manners and mores she had observed at country house parties. Her friend Daisy Warwick found the manuscript highly amusing and used her connections to have it serialized in a London newspaper. The excerpts were published anonymously, but after they became a much-talked-about success, Elinor couldn’t resist stepping forward to take the credit. When

The Visits of Elizabeth

was published in book form in 1901, the career of Elinor Glyn, novelist, was launched. Several more novels followed, but it was the publication of a steamy love story in 1907 called

Three Weeks

that would make her both famous—and notorious. The story of a three-week affair between a handsome young Englishman and an exotic older woman (the queen of an unnamed Balkan kingdom), the novel was based on Elinor’s own short-lived but passionate attachment to a young Guards officer named Alistair Innes Kerr, a son of the Duke of Roxburghe. Friends who read the manuscript urged her not to publish it, but she needed the advance money, as Glyn’s finances were rapidly proceeding from precarious to calamitous. The book was a runaway bestseller—it would eventually sell more than five million copies and be widely translated internationally. But it was a

succès de scandale

—the novel was condemned as unfit for the young and was banned in Boston and, for a time, in Canada. Though tame by modern standards,

Three Weeks

shocked not just because it described adultery and an out-of-wedlock birth, but because it was the story of a brief affair that was initiated, controlled, and finally ended by the female. This contravened all the sexual power conventions of the day, but by so doing Elinor launched a new publishing genre—the erotic romance novel.

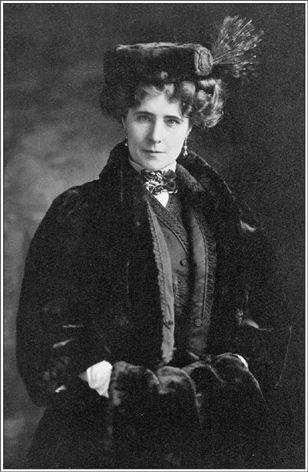

Elinor Glyn

(photo credit 1.39)

The key seduction scene in

Three Weeks

takes place on a couch draped in a tiger skin, which prompted an anonymous bit of doggerel that would forever dog Elinor:

Would you like to sin

With Elinor Glyn

On a tiger skin?

Or would you prefer

To err

With her

On some other fur?

Along with the undulations on tiger skins, clothes are ubiquitous in

Three Weeks

, and many of the shimmering garments described are unmistakably Lucile in style. Lucy would return the compliment by naming a provocative new frock “the Elinor Glyn.”

For her first American publicity tour, Elinor packed several trunks of Lucile-designed clothes, and on arrival in New York harbor on October 5, 1907, she was garbed entirely in purple, including a hat with trailing purple chiffon veiling—all evoking the heroine of her book. The press was captivated, and soon invitations from leading hostesses began arriving at her suite in the Plaza. When Lucy heard of Elinor’s success, she decided to come over in December to scout prospects for a New York branch of Lucile Ltd. While staying with her newly famous sister at the Plaza, she wrote home to Cosmo: “

I’m sure we can make a fortune here, if we can find the money. There are such opportunities of wearing good clothes here.” Lucy returned to London in January while Elinor stayed on in New York, relieved to no longer have to share the spotlight with her sister.

During her New York stay with Elinor, Lucy had noted the value of publicity in making a splash in America. “

The one thing that counts,” she would write, “is self-advertisement of the most blatant sort.” For the New York branch of Lucile Ltd., she found a brownstone on West 36th Street and in late 1909 asked her friend, the pioneering interior designer Elsie de Wolfe, to decorate it in the style of her shop on Hanover Square. Elsie also hired a publicist who generated such a flurry of articles with headlines like

LADY DUFF GORDON, FIRST ENGLISH SWELL TO TRADE IN NEW YORK

that one newspaperman waggishly dubbed Lucile “Lady Muff Boredom.”

Yet the press went into raptures when Lucy arrived on the

Lusitania

in early March of 1910 with four of her statuesque models and a new collection of what she called “dream dresses.” This was a variant on her theme of “personality frocks” or “emotional gowns” where each dress was given a name to reflect its “personality,” whether it be “When Passion’s Thrall Is O’er,” “The Sighing Sound of Lips Unsatisfied,” or “Red Mouth of a Venomous Flower.” In a crasser mode she dubbed part of her American collection “Money Dresses,” and, in case anyone missed the point, explained in her advertising copy, “because it takes so much to buy them.” Such blatancy seems to have discouraged very few, since on opening day orders were taken for over a thousand gowns, none of them costing less then $300 (the equivalent of $6,000 today).

Her fashion shows were so mobbed that lineups of elegant ladies stretched down West 36th Street and Lucile came up with a plan to sell tickets and donate the proceeds to the Actors Fund. Sitting on a divan next to Lucy at the first New York fashion show was her good friend Anne Morgan, daughter of J. P. Morgan and a principal investor in her New York venture. “

Ours was a new playhouse for rich American women,” one of Lucile’s employees would recall. “Never had we seen such extravagance, or seen so little importance attached to the price of clothes.” Lucile’s American clients would range from Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and Alice Roosevelt Longworth to the dancer Irene Castle and the stars of the Ziegfeld Follies. Madeleine Force and her mother would also visit the 36th Street salon to shop for a Lucile trousseau before her 1911 wedding to John Jacob Astor.

Having conquered New York, Lucile’s next pinnacle was Paris. The Parisian designers looked askance at the English invader, but after the opening of her new salon on April 4, 1911, Lucy had the satisfaction of reading in a French newspaper, “

The dramatic performance with which Lady Duff Gordon startled Paris today will be copied by every self-respecting couturier here before long.” Even French

Vogue

would eventually succumb, noting: “

We are so accustomed to having everything of value come out of Paris, that we are amazed to find an Englishwoman making some of the greatest contributions to fashion anyone ever made.” For the girl from the Canadian backwoods who had been thrilled to receive a barrel of cast-off clothes from Paris each year, this must have been a very sweet victory indeed.

The following April she was required in New York to sign the lease for her new shop. “

As business called me over in a great hurry,” she recalled, “I booked passage on the first available boat. The boat was the

Titanic

.” On the platform at the Gare St. Lazare a group of her shopgirls and mannequins showed up to give her a surprise send-off, pressing a basket of lily-of-the-valley into her arms. Usually, a contingent of employees would have traveled with her: “

The designer was accustomed to traveling grandly,” writes her biographer Randy Bryan Bigham, “complete with an armful of Pekinese and an entourage of beautiful models dressed in her latest fashions.” This time, no doubt in deference to Cosmo, she had brought along only her personal assistant, Laura Mabel Francatelli, familiarly known as either “Mabel” or “Franks.”

Lucy would later claim that she had felt some anxiety about making the crossing on a new ship, but once settled in her

Titanic

stateroom, she relaxed. “

Everything aboard this lovely ship reassured me, from Captain Smith with his kindly, bearded face and genial manner … to my merry Irish stewardess with her soft brogue.” Lucile was also delighted with her “pretty little cabin, with its electric heater and pink curtains” that made it “a pleasure to go to bed.” When Lucile did retire for the night, however, it was not with Cosmo, who had his own cabin across the corridor. The relationship that had begun as business now appeared to be mostly about business; in a drama in which she held center stage he had become a supporting player. In photographs, Lucy usually stands apart from Cosmo, staring out at the camera while he casts a puzzled but adoring gaze in her direction.

“

One can only amuse oneself when one has a nice young man,” Lucy had once observed, and she indeed cultivated a constant stream of young male admirers. Cosmo was fairly complaisant about this since most of them were homosexual; a granddaughter remembers that Lucile was “

regularly surrounded by queer gentlemen who were designers in their turn, picked up pins and did her bidding.” Edward Molyneux, whom Lucy called “Toni,” was just one of the protégés who would later become a celebrated designer in his own right. Among her female friends, lesbians were particularly prominent: her closest friends in New York were Elsie de Wolfe and her partner, the theatrical agent Bessie Marbury, as well as Anne Morgan and her lover Ann Harriman Vanderbilt, and in Paris she was friendly with the lesbian novelist Natalie Barney and her circle. Lucy admired these independent, forthright women, and according to Randy Bryan Bigham, “

a sexual ambiguity on Lucy’s part is possible.”

DURING THE

TITANIC

’S

“dressing hour” on Saturday, April 13, Charlotte Cardeza, our lady of the fourteen trunks, may have instructed her maid to select her rose-colored Lucile evening dress from the eleven gowns she had with her. Mrs. Cardeza also owned one of Lucile’s exquisite satin petticoats trimmed with lace and flowers and would list it on her liability claim with a value of $300 ($6,000 today). Marian Thayer, the wife of the Pennsylavania Railroad vice president John Thayer, may also have worn a Lucile gown that evening since she was both a client and a friend of Lucy’s. But no passenger was a better exemplar of the Lucile look than the designer herself.

Vogue

noted that her personal style was very simple though “

smart to the last degree.” Black remained a favorite color, recalling the hand-sewn dress she had worn to her first Government House ball.

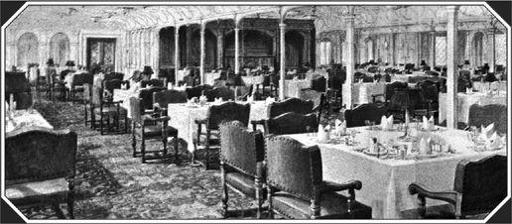

On that Saturday evening, therefore, one can imagine Lucile in a black evening gown, accented by the pearl earrings she often favored, taking Cosmo’s arm as they descended the grand staircase to the dining saloon on D deck. As they stepped onto the blue-and-red-carpeted expanse of the Palm Room, they were greeted by what she described as “

the hum of voices, the lilt of a German waltz—the unheeding sounds of a small world bent on pleasure.” But what she calls in her next sentence the “disaster swift and overwhelming” was now only one night away.

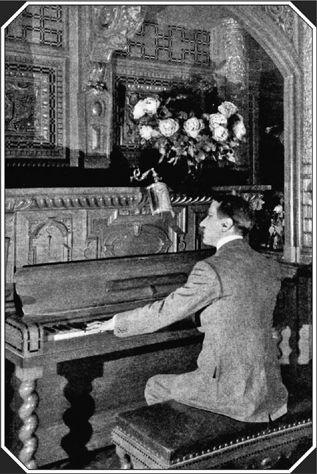

The church service was held in front of a carved oak sideboard (top, at center) in the first-class dining saloon. The piano installed there was reserved for Sunday services.

(photo credit 1.29)